Section A | Performance and financial management reporting

Section A | Performance and financial management reporting

- The Organisation

- Overview

- Submissions and major investigations

- Organisational planning and environment

- Highlights

- Outlook for 2011-2012

- Statement of agency performance

- ACT Government agencies - Approaches and complaints

- ACT Policing - Approaches and Complaints

- ACT Policing - Inspections

The Organisation

The role of the ACT Ombudsman is performed under the Ombudsman Act 1989 (ACT). The Ombudsman also has specific responsibilities under the Freedom of Information Act 1989 (ACT) and the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (Cth), and is authorised to deal with whistle-blower complaints under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1994 (ACT).

The Commonwealth Ombudsman, who is appointed under the Ombudsman Act 1976 (Cth), discharges the role of ACT Ombudsman under the ACT Self-Government (Consequential Provisions) Act 1988 (Cth).

Up until 30 December 2006 the Ombudsman also had specific responsibilities in relation to the AFP under the Complaints (Australian Federal Police) Act 1981 (Cth). Complaints made about the AFP before 30 December 2006 continue to be dealt with under that Act. Complaints made after that date are dealt with under the Ombudsman Act (Cth). In addition, the Ombudsman has a role in monitoring compliance with chapter 4 (Child Sex Offenders Register) of the Crimes (Child Sex Offenders) Act 2005 (ACT) by the ACT Chief Police Officer and other people authorised by the Chief Police Officer to have access to the register.

The ACT Ombudsman is an independent statutory officer who considers complaints about the administrative actions of government departments and agencies. The Ombudsman aims to foster good public administration by recommending remedies and changes to agency decisions, policies and procedures. The Ombudsman also makes submissions to government on legislative and policy reform.

The office investigates complaints in accordance with detailed written procedures, including relevant legislation, a service charter and a work practice manual. It carries out complaint investigations impartially, independently and in private. Complaints may be made by telephone, in person or in writing (by letter, email or facsimile, or by using the online complaint form on our website). Anonymous complaints may be accepted.

The key values of the ACT Ombudsman are independence, impartiality, integrity, accessibility, professionalism and teamwork.

Our clients and stakeholders cover all people who may be affected by the administrative actions of ACT Government agencies and of the AFP in carrying out their ACT Policing role. A services agreement between the ACT Government and the Ombudsman covers the provision of services in relation to ACT Government agencies and ACT Policing.

In 2010-11 the Ombudsman delegated day-to-day responsibility for operational matters for the ACT Ombudsman to Senior Assistant Ombudsman Helen Fleming, and responsibility for law enforcement, including ACT Policing, to Senior Assistant Ombudsman Diane Merryfull and Senior Assistant Ombudsman Adam Stankevicius. The Senior Assistant Ombudsmen are supported by specialist staff in the Territories, Law Enforcement and Inspections' teams in carrying out these responsibilities for the Ombudsman. The Ombudsman and Deputy Ombudsmen maintain an active involvement in the work of these two teams.

Executive Team (from left) Ombudsman Allan Asher, Diane Merryfull, Deputy Ombudsman Alison Larkins, Adam Stankevicius and Helen Fleming

Overview

Summary and complaint statistics

Complaint handling remains the core of the Ombudsman's role. In 2010-11 we received 742 approaches and complaints about the actions of ACT Government agencies (600) and ACT Policing (142). Overall, this was up by nearly 10 per cent on 2009-10 when the office received 676 approaches and complaints (507 about ACT Government agencies and 169 about ACT Policing). However, for ACT Government agencies it was up 19%, with a decrease again for ACT Policing, continuing a 3 year trend.

Housing ACT and ACT Corrective Services (Corrective Services) continue to be the agencies that are the subject of the largest number of government agency complaints that we received (146 and 169 respectively in 2010-11), up again on the previous reporting period. The numbers of complaints about these agencies are not necessarily an indication that they are not performing well, but a reflection of the nature of the role and responsibilities of each agency in the community.

During the period we finalised 774 approaches and complaints, 626 of which were about ACT Government agencies and 148 about ACT Policing. Detailed analysis is provided in the Performance section of this report under the headings 'ACT Government agencies-Approaches and complaints' and 'ACT Policing- Approaches and complaints'.

Submissions and major investigations

An important role of the Ombudsman is to contribute to public discussion on administrative law and public administration and to foster good public administration that is accountable, lawful, fair, transparent and responsive. Also, to achieve more customer-centred public administration. To achieve these outcomes, we made submissions to, or commented on, a range of administrative practice matters, cabinet submissions and legislative proposals during the year. These included:

- input into the Hamburger Review regarding the governance and accountability procedures within the ACT Corrective Services. The Ombudsman's office also provided statistical data on 25 October 2010 for the independent review

- a submission to the independent review of the effectiveness, capacity and structure of the ACT Government public sector (known as the Hawke Report)

- in June 2011, the Ombudsman made four recommendations when he released a report about Housing ACT's management of an application for Priority housing for a vulnerable person. The report, Housing ACT: Assessment of an application for priority housing -01/2011 (see case study 'Flexible Policy') is an example of how things can go wrong if policies are inflexible.

Organisational planning and environment

The 2010-13 strategic plan for the Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman sets out strategic objectives for that period. Each year the Ombudsman and Deputy Ombudsman review the plan and establish the priorities for the next year with strategic planning underway for 2011-2014.

In 2011-12, the Ombudsman's office will continue its focus on significant systemic issues arising from complaints, inspections and monitoring with a focus on our 10-Point Plan improve ACT Government service delivery (Appendix 3). We will continue our endeavours to improve structures and processes to deliver efficient, practical, higher quality and more consistent responses to complaints. The strategic priorities of the office are to:

- improve quality assurance and review of complaint handling

- build on the work practices and system changes to deliver improved quality, efficiency and consistency in managing complaints

- develop an enhanced approach to social inclusion and effective interaction through social media

- targetted outreach, relevant publications and communication activities to key stakeholders, particularly through community intermediaries

- be responsive to areas of need in allocating resources.

Detailed reporting on a range of office-wide initiatives against the priorities for 2010-11 is provided in our Commonwealth Ombudsman Annual Report, available on our website (www.ombudsman.act.gov.au) from late October 2011.

In June 2011 we made further changes to our online complaint form. This form helps people understand the role of the Ombudsman and is a step by step guide to assist complainants when lodging a complaint including an option to upload documents. Our website has helpful links to information on other government agencies which may assist.

Highlights

Complaint service

The Public Contact Team (PCT) provides professional first line contact for members of the ACT community making enquiries and lodging complaints with the Ombudsman's office. The team sustains a complaint intelligence gathering function with which to support the Territories Team.

The main role of the PCT is to:

- provide professional initial interaction with members of the public via telephone and in person

- respond to incoming documents we receive via email, internet (including electronic complaints), fax and normal post

- resolve enquiries and out of jurisdiction complaints.

The Territories Team provides training sessions to new PCT staff on the role and jurisdiction of the Ombudsman. The Territories Team also supplements the PCT's ongoing training program to ensure that approaches to the office are efficiently and effectively handled in the first instance. In circumstances where an approach is not within jurisdiction, the PCT provides guidance and contact details for other agencies that may assist the complainant, such as the Children and Young People Commissioner and the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

Periodically the office undertakes surveys of complainants and agencies, as this is one way to measure our performance and to identify areas for improvement in service delivery. Such surveys also provide information that helps us better target our outreach activities. Planning is underway for a client-satisfaction survey in early 2011-12.

Public administration and complaint handling

The Ombudsman continued to contribute to improvements in public administration by participating in specific projects, investigating and resolving complaints from individuals and by identifying systemic problems in public administration.

The Commonwealth Ombudsman continued to promote the Better Practice Guide to Complaint Handling as published in April 2009. The guide builds on previous Ombudsman publications by defining the essential principles for effective complaint handling, and we promote this guide to ACT Government agencies when developing or evaluating their own complaint-handling systems.

We continued to have regular liaison with ACT agencies and with agency contact officers. These meetings assist in maintaining a good working relationship with agencies which is important for timely and effective resolution of complaints.

We have provided significant input into ACT Government initiatives during the year, including participation in the following projects:

- contribution into the publication of the independent review of the effectiveness, capacity and structure of the ACT public sector (known as the Hawke Report)

- contribution into the Hamburger Review which focused on the first 12 months of operation of the Alexander Maconochie Centre

- liaison meeting with the Burnett Institute and Mary Durkin the Health Services Commissioner to discuss health services at the Alexander Maconochie Centre.

Under s 40XA of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (Cth), the Ombudsman,as Commonwealth Ombudsman, has aresponsibility to review the administrationof the AFP's handling of complaints, throughinspection of AFP records. This includes recordsof the handling of complaints about ACTPolicing. Further details are in the 'Performance'section of this report under the heading'ACT Policing-Approaches and complaints'.Public awareness and agency surveys

The Ombudsman's office conducts triennial periodic surveys measuring client satisfaction with our complaint handling services, public awareness of the role and services of our office, and the experiences of our counterparts in Australian and ACT Government agencies in their dealings with our office. In 2010-11 our office engaged an independent social research consultancy to conduct two surveys.

Public awareness survey

The public awareness survey sampled 2487 people living in metropolitan, regional, rural and remote areas in all states and territories. The survey was designed to test their awareness about, and attitudes to, the work of the Ombudsman's office. The field work was conducted in June 2011 through telephone interviews, online surveys and intensive one-on-one discussions with senior representatives of organisations acting as advocates or frontline service providers for vulnerable and disadvantaged individuals and communities.

While the research did not identify issues or concerns particular to ACT residents, the findings suggests that three sections of the community are disadvantaged in their access to our services nationally:

- women of all ages, but especially in age groups younger than 55 years

- young people aged 18 to 24 years and young adults aged 25 to 34 years

- people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, especially newly emerging migrant communities.

The research identified several factors mitigating the access of these demographic groups to our services. They are threefold:

- lower awareness about the role and services of the ACT Ombudsman and ombudsman services generally

- greater uncertainty about their rights as citizens and what might constitute unfair treatment by a government agency

- greater reluctance to complain when they feel they have been treated unfairly or unjustly, or that the decision by a government agency was wrong, unlawful or discriminatory.

The office of the ACT Ombudsman is actively developing strategic collaborations with community service agencies operating across the fields of youth, women and culturally and linguistically diverse communities to advance our vision of equitable, fair and just access to services regardless of age, gender or ethnicity.

Australian and ACT government agency survey

Our second survey of the year sought to identify the attitudes and perceptions of ACT Government agencies in their dealings with the ACT Ombudsman's office, including their satisfaction levels with those dealings. The research was part of a larger survey that sampled all Commonwealth and ACT Government departments and agencies about which the Ombudsman's office had received five complaints or more from the public in the preceding financial year. Twenty ACT Government departments and agencies met this criterion.

Through anonymous online surveys of our counterparts in these agencies, supplemented by intensive one-one interviews with senior executive staff, the research identified:

- a high level of understanding of the roles, powers and authority of the Ombudsman's office

- a high level of satisfaction with the Ombudsman's staff and our procedures in compliant handling case management and attendant negotiations

- wide-spread respect and recognition of the Ombudsman's independence and impartiality

- a keen interest for the Ombudsman's office to provide training and seminars on best practice in complaint handling and administrative law

- a desire for closer liaison with the Ombudsman's office on complaint and complainant issues and trends through roundtables and feedback forums.

The Ombudsman's office is encouraged by this research to further fund its commitment to initiate dialogue and training on better citizen-centric and socially inclusive practices by government.

Outlook for 2011-2012

We intend promoting our 10-Point Plan to improve ACT Government service delivery. We will also continue our program of contact officer forums for ACT Government agencies' complaint contact officers and further promote our Better Practice Guide to Complaint Handling .We will also promote the Better Practice Guide to Managing Unreasonable Complainant Conduct in the ACT Government sector as a valuable tool for helping agencies to resolve difficult situations in the most efficient and effective manner possible.

We actively encourage agencies to seek our participation in their internal training sessions.

As a result of closer involvement in training programs, this office will be able to develop training aids that target the information needs of ACT Government agencies about the functions of the Ombudsman. We will also be able to target information sessions based on the specific issues relevant to the individual agencies.

We will continue our focus on improving web based services, including our revised online complaint form, twitter and other social media. We also intend to findings ways of engaging with the vulnerable in the community.

Finally, there will be continued pressure on our resources. We need to continue to improve both the efficiency and effectiveness of our complaint handling and broader work.

Statement of agency performance

Summary of performance

In 2010-11, the ACT Government paid an unaudited a total of $1,031,206 (including GST) to the Ombudsman's office for the provision of ACT Ombudsman services.

The Ombudsman is funded under a services agreement with the ACT Government which was signed on 31 March 2008. Payments (including GST) were for the purposes of the Ombudsman Act 1989 (ACT) ($485,436) and for complaint handling in relation to ACT Policing ($545,770).

The office is negotiating with the ACT Government for an increase in funding to adequately cover increased complaint handling work, own motion complaints and increased inspections responsibilities.

The office's performance against indicators is shown in Table 1. Further detail is available under the headings 'ACT Government agencies - Approaches and complaints', 'ACT Policing - Approaches and complaints' and 'ACT Policing - Inspections'.

Table 1: Summary of achievements against performance indicators, 2010-2011

Performance indicators | ACT Government agencies | ACT Policing |

Number of approaches and complaints received | 600 approaches and complaints (507 in 2009-2010) | 142 approaches and complaints (169 in 2009-2010) |

Number of approaches and complaints finalised | 626 approaches and complaints (490 in 2009-2010) | 148 approaches and complaints (167 in 2009-2010) |

Time taken to finalise complaints | 82% of all complaints finalised within three months (86% in 2009-2010) | 91% of all complaints finalised within three months (89% in 2009-2010) |

The statistical report in Appendix 1 provides details of complaints received and finalised, and remedies provided to complainants, in 2010-11.

The categories of approaches and complaints to this office range from simple approaches that can be resolved with minimal investigation to more complex matters requiring the office to exercise its formal statutory powers. In all approaches that require investigation, we contact the agency to find out further information about the complaint and to provide the agency with an opportunity to respond to the issues raised in the complaint. Often an approach from this office to the agency assists in resolving the complaint in the first instance.

Where a complaint involves complex or multiple issues, we conduct a more formal investigation. The decision to investigate a matter more formally can be made for a number of reasons:

- a specific need to gain access to agency records

- the nature of the allegations made by a complainant require records to be provided

- if there is likely to be a delay in the time taken by an agency to respond to our request for information

- the likely effect on other people of issues raised by the complainant

- the agency requests that formal powers are used in an investigation.

Not all of the approaches we receive are complaints that are within the jurisdiction of the Ombudsman. We refer people to other oversight agencies that are established to handle specific types of complaints such as the Human Rights and Discrimination Commissioner and the Children and Young People Commissioner. There are some issues that are not within the jurisdiction of the Ombudsman, such as employment-related matters or decisions of courts or tribunals. In these cases, we inform the person of the role of the Ombudsman and the limits of our jurisdiction. We try to assist by directing them to the relevant areas and provide information and contact details.

Liaison and training

This office aims to develop a better understanding by the public and by agency staff of the role and responsibilities of the Ombudsman. We engage in community outreach activities that assist to promote this better understanding. In 2010-11 this included:

- promoting the Ombudsman role to students during Orientation Week activities at the University of Canberra and the Canberra Institute of Technology

- participation in training for the ACT Corrective Services' new recruits on the role and responsibilities of the Ombudsman

- outreach with the Australian National University and the Alexander Maconochie Centre to support 'books for all', a campaign to raise money for the purchase of additional books for the Centre library

- promoting the Ombudsman role at a breakfast for the Council of the Ageing

- meeting with the Commissioner for Public Administration in relation to the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1994 .

Ombudsman staff participated in formal and informal meetings with ACT Government agencies and conducted information and training sessions throughout the ACT Government sector and inspections of ACT Government facilities. This liaison and training is important for the effective and efficient conduct of our complaint investigation role. Activities included:

- regular information sessions as part of the induction process of ACT Corrective Services staff as well as whole of Alexander Maconochie Centre information sessions

- regular meetings with senior staff in ACT Government agencies to provide feedback on complaints received and to ensure smooth handling of complaints

- input into publications including the Hawke Report which focused on the structure and capacity of the ACT public sector; and the Hamburger Review regarding the governance and accountability procedures within the ACT Corrective Services

- a liaison meeting regarding the implementation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice Agreement

- an inspection of the Periodic Detention Centre

- an inspection of detainee property at the Alexander Maconochie Centre's admissions area.

The Ombudsman's office maintains contact with the community in a variety of formal and informal ways.

This aspect of our work is important in raising public awareness of the right to complain to the Ombudsman and building confidence in the role of the office in managing and investigating complaints about ACT Government agencies and ACT Policing. During 2010-11 we:

- conducted outreach activities during Orientation Week at the University of Canberra and the Canberra Institute of Technology

- met with the trainee staff of ACT Corrective Services to explain our role

- hosted a half-day ACT Agency Contact Officers Forum to promote best practice in complaint handling

- liaised with the Burnett Institute and Mary Durkin the Health Services Commissioner to discuss health matters at the Alexander Maconochie Centre.

Service charter standards

The Ombudsman Service Charter sets out the standard of service that can be expected from this office, explains how complainants can assist us to help them and provides them with an opportunity to comment on our performance.

We regularly monitor our performance against the service charter standards and assess ways to promote further improvement. This feedback enables us to improve our service. The service charter is available at our website (www.ombudsman.act.gov.au).

If a complainant disagrees with the conclusions about a complaint, they can request a review. The reasons for seeking a review should be provided as this assists the office to fully understand the complainant's concerns.

Late in 2009 a new approach to dealing with requests for reviews was adopted. A central team considered whether a review should be undertaken and then conducted the review if required. In some cases, the person may just need a clearer explanation of information we have already provided, or, they may have misunderstood our role, and further investigation is not necessary. The aim of this approach was to provide greater consistency and timeliness of reviews.

It is important to assess the likelihood of a better outcome for a complainant should a review proceed. This helps ensure that the office's resources are directed to the areas of highest priority. If, as a result of a review, investigation or further investigation is required, the review team provides the complaint to a senior staff member to decide who should undertake the investigation or review.

With this in mind we are once again we are looking at new ways of dealing with reviews.

During 2010-11 we dealt with ten requests for reviews. All ten related to ACT Government agencies and four involved ACT Policing.

With respect to ACT Government agencies, in four cases the original decision was affirmed. In one case, the complaint was referred back to the relevant team for investigation or further investigation. One case is under consideration.

The main method by which we gauge the level of satisfaction with the quality of our services is through periodic surveys of people and agencies in who we have had contact. In 2010-11 we commissioned an independent market research company to undertake an ACT Government survey and public awareness survey. This is reported on in Highlights. The next Client-satisfaction survey will be undertaken 2011-2012.

Ongoing challenge

Challenges for this office in 2011-12, will be to promote the 10-Point Plan to improve ACT Government service delivery.

Over the reporting period we saw continuing pressure on resources and timeliness of complaint handling. Nonetheless, it is our role to deliver high quality service in a timely manner. Accordingly, we will continue to review processes, training and technical support to find the means to improve timeliness in particular. We will continue to negotiate with the ACT Government about resourcing levels.

ACT Government Agencies - Approaches and complaints

Approaches and Complaints - received

Complaint handling remains the core of the ACT Ombudsman's role. In 2010-11 we received 600 approaches and complaints about ACT Government agencies, 93 more than the previous year.

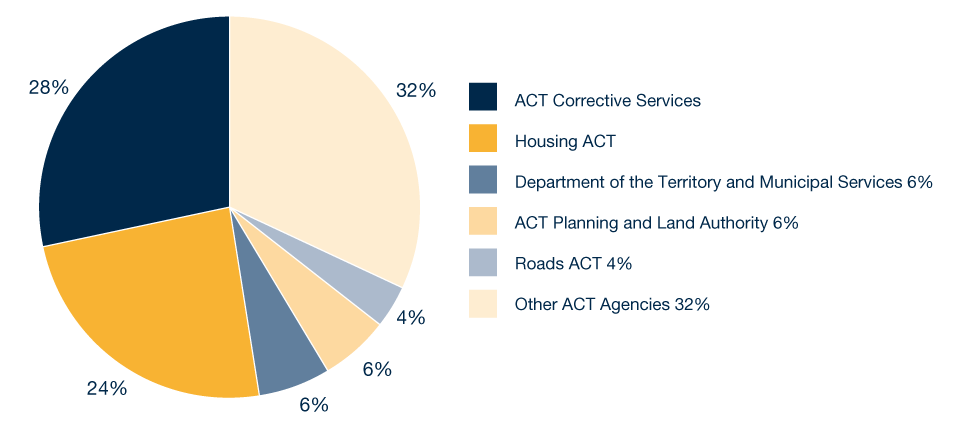

Housing ACT and ACT Corrective Services (Corrective Services) continued to be the agencies that are the subject of the largest number of government agency complaints that we received (24 per cent and 28 per cent respectively in 2010-11).

Of the remaining top five ACT agencies for complaints received in 2010-11, the Department of Territory and Municipal Services and ACT Planning and Land Authority accounted for six (6) per cent each of complaints received and Roads ACT four (4) per cent.

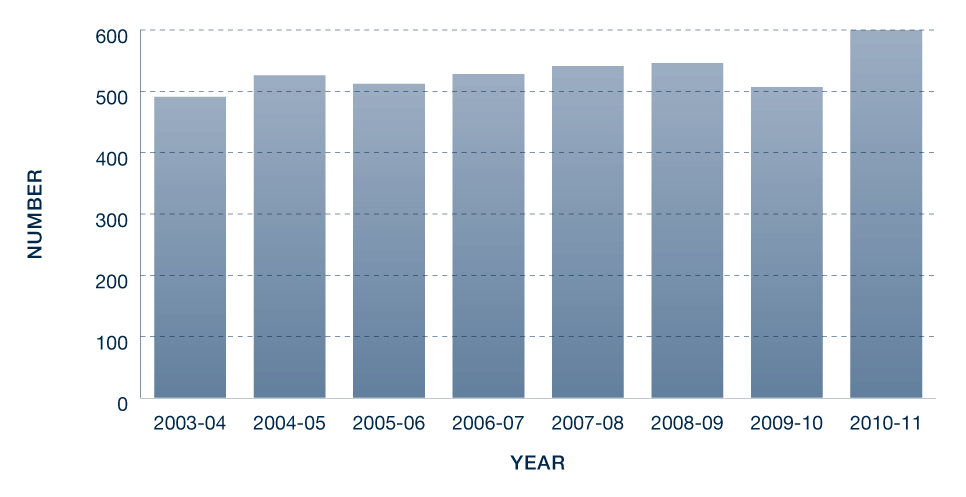

Figure 1 provides a comparison of approaches and complaints received about ACT Government agencies for the eight-year period 2003-2004 to 2010-11. Figure 2 over the page, provides an illustration of the spread of approaches and complaints received across ACT Government agencies.

Figure 1: Approaches and complaints received about ACT Government agencies, 2003-2004 to 2010-11

Figure 2: Spread of approaches and complaints received about ACT Government agencies, 2010-2011

Table 2 below provides a comparison of the top five ACT agencies for complaints received by number.

Table 2: Complaints received by agency

Agency | 2009-10 | 2010-11 |

|---|---|---|

ACT Corrective Services | 144 | 172 |

Housing ACT | 103 | 156 |

Department of Territory and Municipal Services | 53 | 46 |

ACT Planning and Land Authority | 24 | 36 |

Roads ACT | 5 | 21 |

Other agencies | 161 | 195 |

Total | 490 | 626 |

Most complaints received involve agency record keeping standards and complaint handling mechanisms. Case studies of some of the complaints that we received regarding these agencies are explored under 'Complaint themes'.

Approaches and Complaints - finalised

During 2010-11, we finalised 626 approaches and complaints about ACT Government agencies, compared with 490 in 2009-10. This year we investigate 24% of the complaints we finalised, up marginally on the last year.

Table 3 below provides a comparison of the top five ACT agencies for complaints finalised by number.

Table 3: Complaints finalised by agency

Agency | 2009-10 | 2010-11 |

|---|---|---|

ACT Corrective Services | 151 | 169 |

Housing ACT | 106 | 146 |

Department of Territory and Municipal Services | 58 | 36 |

ACT Planning and Land Authority | 27 | 35 |

Roads ACT | 5 | 22 |

Other Agencies | 160 | 192 |

Total | 507 | 600 |

We encourage complainants in the first instance to approach the agency that is the subject of the complaint. This provides the agency with an opportunity to deal with the approach using their complaint-handling procedures and to resolve the issue.

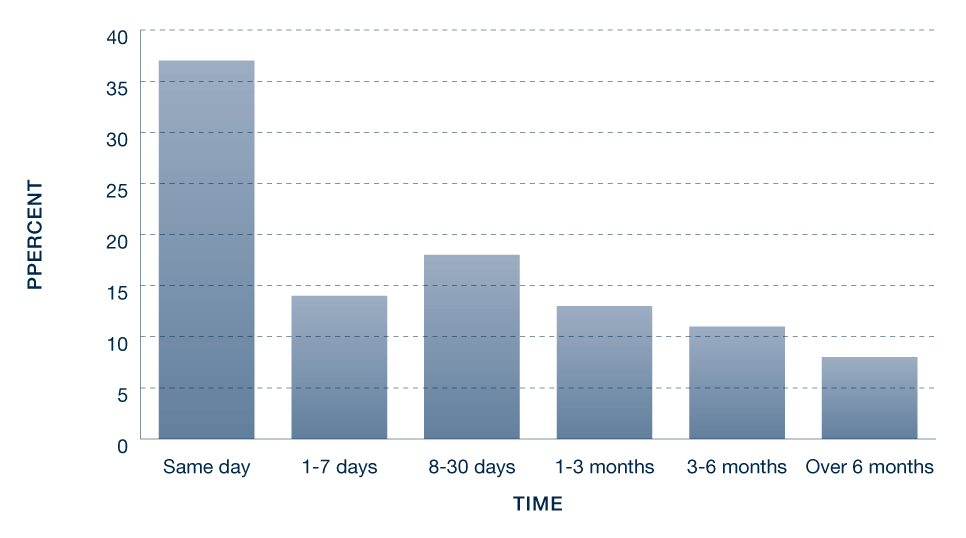

During 2010-11, 51% of the complaints we finalised were done so within one week and 82% within three months (see Figure 3). This is lower than in 2009-10, where it was 55% within one week and 86% in three months, reflective of the increased volume of complaints received.

Of the remaining approaches and complaints, 11% were completed in three to six months and 8% took more than six months to complete.

Figure 3: Time taken to finalise approaches and complaints about ACT Government agencies, 2010-11

Complaint themes

The Ombudsman identified a number of themes arising out of complaint handling and our contact with agencies during the year. The themes related to confidentiality and privacy issues in complaint handling and record keeping remains a recurring issue. We also highlighted the need for improving information to the public, the need for flexible policies and maintaining contact with complainants.

Privacy and confidentiality

Under the ACT Ombudsman's Act 1989 , the Ombudsman is able to provide an independent and impartial oversight on matters dealing with privacy and confidentiality. Where for privacy reasons complainants are not permitted to know the outcome of investigations involving a third party, we can provide independent assurance that a matter was handled in accordance with policy and legislation and the decision was one that was reasonable.

The following case (Ms A) over the page, demonstrates how the Ombudsman can provide independent assurance that an ACT Government agency's decision making was reasonable in the circumstances, whilst maintaining utmost privacy and confidentiality.

Independent assurance that decision making was reasonable

Ms A was dissatisfied with an ACT Government agency handling of her complaint about an allegation of an inappropriate email from a colleague. Ms A has requested that the Department investigate her complaint. After a four month investigation, the Department found that the communication to Ms A was inappropriate and acknowledged Ms A felt harassed over the matter. However, the investigation also found that there was no intention to harass on behalf of the colleague.

Ms A disagreed with this decision and approached the Ombudsman for a review of the matter.

One of the issues under contention was the limitation on the disclosure of personal information to Ms A under the Privacy Act 1988 . Whilst the Act precludes the disclosure of personal information to an unauthorised third party, the ACT Ombudsman Act 1989 allows an investigation officer to receive all records relevant to the investigation of a complaint. Whilst also bound by the Privacy Act, the release of confidential and personal information to the Ombudsman allows for a full and impartial review.

Through our enquiries, we established that whilst not all outcomes of the investigation could lawfully be communicated to Ms A, we were able to assure her that the decision making process was reasonable.

Record keeping

We encourage government agencies making decisions that impact on members of the community to provide reasons and explanations that are clearly articulated. Some problems that give rise to complaints are inevitable. Decisions about complex technical matters can be difficult to get right particularly where discretion is required. It is important that decisions are documented, supported by legislation and consistent with policy. Officers need to consider all the facts and any discretionary powers need to be applied fairly and impartially (with appropriate delegation).

The next case study (Mr B) represents the unintended consequence of a strict interpretation of the relevant legislation and the resultant poor record keeping practice of the agency concerned.

Frivolous or not frivolous: That is the vexed question

Mr B lodged a complaint with this office in regard to difficulties he was having in lodging nuisance noise complaints (barking dogs) with ACT Domestic Animal Services (the Agency). Mr B advised our office that he was categorised as 'frivolous' on his second attempt to lodge a complaint with the Agency for a similar problem regarding animal noise in his street. Mr B lodged a complaint a number of months prior to this, which the Agency was unable to resolve.

In our investigation of Mr B's complaint, we established that the Agency had declined to investigate Mr B's complaint. Under the relevant legislation it was mandatory for all complaints to be investigated unless the matter is determined to be frivolous. Accordingly, the Agency decided to categorise Mr B's complaint as 'frivolous' and declined to investigate his second complaint.

The Agency advised that it recognised that procedural fairness and natural justice had not been observed and now had the view that decision may have been premature. The inflexibility inherent in the legislation obliged the Agency to either investigate or find a complainant frivolous; there was no middle ground.

Given the limited options to deal effectively with animal complaints, we suggested the Agency may wish to consider amending its policy for investigating complaints rather than recording that a complainant is 'frivolous' if the decision by the Agency was not to investigate a complaint. We also suggested that the Agency may also wish to consider whether an amendment to the legislation would better serve its purposes.

The following case (Ms C) illustrates where detriment was caused to the complainant where the Agency did not keep their record keeping up to date.

No evidence of notice

Ms C complained to this office in regard to the unexpected extended suspension of her drivers licence. She was advised by an officer at Canberra Connect in September 2010 that she would be required to cease driving her vehicle as of midnight for three months. She subsequently approached Canberra Connect on in December 2010 to confirm that her suspension was to expire the following day. Ms C was advised by Canberra Connect that her suspension did not begin until October 2010, and would not expire until January 2011. Ms C said the officer advised her that this information would have been included on the suspension notice issued to her in September. Ms C advised us that no written correspondence was recieved from Roads ACT regarding her suspension.

Our investigation into the matter revealed that a suspension to Ms C's licence was warranted, however, it did not appear that any notice of suspension had been issued to her. It was discovered that the external service provider for Roads ACT had not kept any copies of suspension notices issued to drivers until October 2010 after Roads ACT had requested the service provider to start keeping copies of suspension notices.

Roads ACT issued an apology to Ms C in regard to her unexpected extension to her suspension. Roads ACT also acknowledged that in November 2010, as part of the normal practices of the department, Road User Services reviewed the way it handled notifications to licence holders. Roads ACT stated that following this review, it has now implemented a new procedure to better store and retrieve copies of notifications issued to suspended licence holders.

Improving information to the public

The Ombudsman encourages ACT Government agencies to ensure that public information is accessible, inclusive, comprehensive, informative and written in plain language.

The next case (Ms D) deals with improving agency relations with the public by publishing accessible and relevant information upfront.

Then in the case that follows on, we were able to advise the complainant (Ms E) that the information on an agency's website was not deficient.

Publishing public information upfront

Ms D advised our office that the ACT Gambling and Racing Commission (the Commission) declined to investigate a complaint she had about an incident that occurred with respect to access to gambling machines at an ACT club. Ms D advised that she requested a statement of reasons relating to the Commission's decision not to investigate her complaint and this request was also declined.

From our investigations it was evident that the Commission had considered all aspects of Ms D's complaint and had endeavoured to provide her with all available information. It was established that that the decisions and actions of the Commission were open to them under legislation and were not unreasonable.

We advised the Commission that the public information then on the Commission's website did not explain the specific nature of their investigative role and powers. It was suggested that a clearer definition of the Commission's complaint-handling role and the complaints that can or will be investigated by the Commission might reduce any confusion for future complainants. The Commission's response was to amend the information on its website to include better clarification on the Commission's role.

Website information established as sound

Ms E approached our office about her dissatisfaction with ACTION regarding the fact that she had received parking infringements having utilised its Park and Ride Service. She felt that there was insufficient information on the ACTION website for her to make an informed view as to whether the Park and Ride Service was appropriate for her circumstances.

Upon investigation, it was established that the ACTION website was reasonably comprehensive and contained sufficient information to allow the public to inform themselves of the terms and conditions of use of the Park and Ride Service. Further, it was confirmed that the information was clear and written in plain language.

Maintaining contact with the client

We receive a number of complaints from people who have not been advised of the outcome of their complaint with an agency. Often the agency is actively dealing with the complaint but have inadvertently neglected to keep the complainant advised of the progress of the matter. In our view, improving service delivery and customer contact in this regard will go a long way in facilitating a more positive experience of the complainant's dealings with that agency.

No communication about birth certificate

Mr F had complained to the Ombudsman that he felt that there had been no progress on his matter with the Births, Deaths and Marriages Unit of the Office of Regulatory Services regarding an application to obtain his birth certificate from interstate.

The Office of Regulatory Services had introduced an initiative to assist members of the indigenous community to register their births and assist where possible to in obtaining their birth certificates, irrespective of whether being born in the ACT or interstate.

Periodically an application from a party can become a complex inter-jurisdictional matter that may take some time to resolve. Upon investigation, we were of the view that the Office of Regulatory Services had done significant work 'behind-the scenes' but overlooked to inform Mr F on a regular basis as to the progress on his matter.

Systemic issues

Record keeping remains as challenge for agencies. We highlighted this issue in the 2009-2010 Annual Report and note that this year further cases have been noted where poor record keeping has led to mistakes that continue to impact of good administration.

In this case (Mr G) over the page, poor decisions by the agency were hampered by poor record keeping practices.

Keeping appropriate records

Mr G was a detainee of the Alexander Maconochie Centre. Upon admission, a number of personal effects were held in possession on his behalf by the Centre. Subsequent to his admission, Mr G complained to the Ombudsman that his personal effects were missing and that he was dissatisfied with Centre's handling of his complaint.

In conducting the investigation, the Ombudsman observed that there were significant difficulties in verifying as to whether Mr G had sold or traded his property to other detainees or had otherwise consented for other parties to acquire them. Furthermore, insufficient record keeping practices meant that there was not a proper audit trial of personal items stored in the Centre's admissions records and those issued to the detainee.

Our analysis determined some potential short-comings in the Centre's dealings with detainees' property management. To this end, the Centre has agreed to maintain proper records in this regard and Mr G's personal effects were either replaced or restored to his rightful ownership.

Cross agency issues

From time to time the Ombudsman receives complaints that may encompass issues beyond our jurisdiction to investigate and resolve. We liaise with agencies to determine which office is better suited to deal with the issues of the complaint (see Commissioner for the Environment section).

Reports released

Under the Ombudsman Act 1989 (ACT), the Ombudsman investigates the administrative actions of ACT Government agencies and officers. An investigation can be conducted as a result of a complaint or on the initiative (or own motion) of the Ombudsman.

Most complaints to the Ombudsman are resolved without the need for a formal finding or report. The above Act provides (in similar terms) that the Ombudsman can culminate an investigation by preparing a report containing the opinions and recommendations of the Ombudsman. A report can be prepared if the Ombudsman is of the opinion that the administrative action under investigation was unlawful, unreasonable, unjust, oppressive, improperly discriminatory, or otherwise wrong or unsupported by the facts; was not properly explained by an agency; or was based on a law that was unreasonable, unjust, oppressive or improperly discriminatory.

A report by the Ombudsman is forwarded to the agency concerned and the responsible minister.

If the recommendations in the report are not accepted, the Ombudsman can choose to furnish the report to the ACT Chief Minister or the ACT Legislative Assembly.

These reports are not always made publicly available. The Ombudsman is subject to statutory secrecy provisions, and for reasons of privacy, confidentiality or privilege it may be inappropriate to publish all or part of a report. Nevertheless, to the extent possible, reports by the Ombudsman are published in full or in an abridged version. Copies or summaries of the reports are usually made available on the Ombudsman website (www.ombudsman.act.gov.au).

The Ombudsman encourages agencies to ensure that they maintain an appropriate level of procedural assistance in their application of policy, especially in cases dealing with vulnerable persons. Being the subject experts of their relevant functions, agencies should wherever possible promote extra assistance to those who have more specialised and imminent needs.

In June 2011 the Ombudsman publicly released a report into the Housing ACT's handling of an application for priority housing. The following case study (Ms H) over the page is an example where we were of the view that the agency did not act reasonably in the circumstances in its provision of services to the disadvantaged.

Inflexible application of agency policy

Ms H, a single mother with several children, complained to the Ombudsman about having been on Housing ACT's High Needs housing list for six months and not receiving any assistance from them. Ms H had been living in short-term rental accommodation that she could not afford. She had fallen behind in her rent and had received an eviction notice.

Ms H applied for housing assistance with supporting documentation attesting to her needs and those of her children. About one month later she attended an assessment interview with Housing ACT and was deemed eligible for High Needs housing, the second of Housing ACT's three needs categories.

On several occasions during the intervening months Ms H provided further documentation to Housing ACT that demonstrated that her situation was serious and deteriorating. Each time Ms H did so she was advised that her application for housing had been re-assessed and remained on the High Needs housing list.

Although Housing ACT had initially informed Ms H of her right to request a review in writing, the information was not presented in a manner that clearly advised her of the procedure and nor was it conveyed to her when she submitted further written documentation supporting her claim. Because Ms H did not formally request that the decision be reviewed, her application remained in the High Needs category, greatly reducing the likelihood of her receiving the public housing accommodation she and her children needed.

Based on our investigation of Ms H's complaint, we formed the view that Housing ACT had not provided Ms H with a level of procedural assistance that was reasonable for a housing applicant in her circumstances. Housing ACT did reassess Ms H's situation and she was subsequently rehoused appropriately. Housing ACT also agreed to review its practices and procedures in this regard.

Update from last year

We have continued our program of Contact Officer Forums for the ACT Government Agency's complaint officer. We also intend to expand on this aspect of agency contact to include regular contact with priority stakeholder engagement group including people with mental health issues, Indigenous people, new arrivals to Australia and the homeless.

Stakeholder engagement, outreach and education activities

The Ombudsman continues to contribute to improvements in public administration by participating in specific projects, investigating and resolving complaints from individuals and by identifying systemic problems in public administration.

The Commonwealth Ombudsman continues to promote the Better Practice Guide to Complaint Handling as published in April 2009. The guide builds on previous Ombudsman publications by defining the essential principles for effective complaint handling, and is being used by ACT Government agencies when developing or evaluating their complaint-handling systems.

We continued to have regular liaison with ACT agencies and with agency contact officers. These meetings assist in maintaining a good working relationship with agencies which is important for timely and effective resolution of complaints.

We have provided significant input into ACT Government initiatives during the year, including participation in the following projects:

- contribution into the publication of the independent review of the effectiveness, capacity and structure of the ACT public sector (known as the Hawke Report)

- contribution into the Hamburger Review which focused on the first 12 months of operation of the Alexander Maconochie Centre

- liaison meeting with the Burnett Institute and Mary Durkin the Health Services Commissioner to discuss health matters at the Alexander Maconochie Centre.

Looking ahead

In September 2010 the ACT Chief Minister, Mr Jon Stanhope MLA announced a review of the ACT Public Sector to be conducted by Dr Allan Hawke AC. In February 2011 the report was published and proposed a number of changes to the ACT Government structure. In June 2011 the new Chief Minister, Ms Katy Gallagher MLA, implemented a number of changes to the structure of the ACT Government. The new structure consists of nine Directorates. Some Directorates share similar responsibilities which had once been under one portfolio.

Where some agencies' responsibilities have been split between other Directorates, it will not be possible to compare complaint trends from previous Annual Reports. Our office is currently reviewing our case management system to align it with the new ACT structure.

The Ombudsman proposed a 10-Point Plan to improve Government service delivery for the coming year (complete copy of the 10-Point Plan can be found at Appendix 3):

- Clarify the new government structure and its areas of responsibility by:

- clearly and accessibly informing the public of specific areas responsible for particular services

- listing contact/access points for services, complaints and submissions.

- Introduce a consistent complaint-handling structure across the whole of government. Specifically:

- provide clear information about making and progressing complaints

- adopt an agreed definition of what constitutes a complaint

- introduce consistent ACT Government complaint service standards

- ensure better processes and IT systems.

- Move away from a culture of denial and defensiveness to one that welcomes complaints and Ombudsman reports as a means of improving service delivery.

- Commit to ongoing training and career development for ACT Government employees, and greater involvement with agency strategic planning.

- Introduce consistent case management systems servicing ACT Government agencies.

- Use plain language information in communication.

- Improve the approach to decision making by:

- providing clear reasons for decisions in a language the client can understand

- ensuring rights of review are clearly stated and explained.

- Improve contract management by giving powers to the Ombudsman's office to oversee third-party service providers. (Most other state and territory ombudsmen have these powers).

- Ensure that officers/agencies responsible for maintaining carriage of service requests and applications are clearly identified.

- Introduce a program of regular inspections covering the broad range of conditions and services available at and via ACT Corrective Services.

ACT Policing - Approaches and Complaints

Overview

In the ACT, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) undertakes community policing governed by an agreement between the Commonwealth and the ACT Governments. The AFP provides policing services to the ACT in areas such as traffic law, crime prevention, maintaining law and order, investigating criminal activities and responding to critical incidents.

Complaints about the AFP made since 30 December 2006 are dealt with by the AFP under the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (AFP Act) and may also be investigated by the Ombudsman under the Ombudsman Act 1976 (Cth). The Ombudsman does not oversight the AFP's handling of every complaint, but is notified by the AFP of complaints it receives which are categorised as serious conduct issues (Category 3 issues). The Ombudsman reviews these complaints annually.

If a complainant is not satisfied with the outcome of the AFP's own investigation, the person can complain to this office which then decides whether to investigate the matter.

Complaints made about the AFP and its officers acting in their ACT Policing role are dealt with by the Law Enforcement Ombudsman under Commonwealth jurisdiction and through an agreement with the ACT Government. The Law Enforcement Ombudsman is also the ACT Ombudsman and the Commonwealth Ombudsman.

Complaint themes

In 2010-11 we received 142 approaches and complaints about the actions of AFP members in their ACT Policing role. This is a reduction of 37 from 2009-10. The most common complaints were about:

- inappropriate action (51)

- police misconduct (minor 13, serious 13)

- customer service (27)

- police practices (18)

- use of force (7).

Some of the complaints also related to the adequacy of AFP investigations, failure to act and unreasonable delays in investigating complaints.

Complaints finalised

In 2010-11, we finalised 148 approaches and complaints. As is our usual practice with complaints, we referred 95 of these back to the AFP as the complainants had not previously approached that agency to seek resolution of their concerns. In eight cases, we advised the complainants to pursue their issues in a court or to contact a more appropriate oversight agency.

We decided not to investigate 23 of the approaches and complaints, for reasons such as:

- an investigation was not warranted in all the circumstances

- the matter had been considered by a court

- the matter was out of jurisdiction

- the complainant was aware of the matter more than 12 months before approaching the Ombudsman.

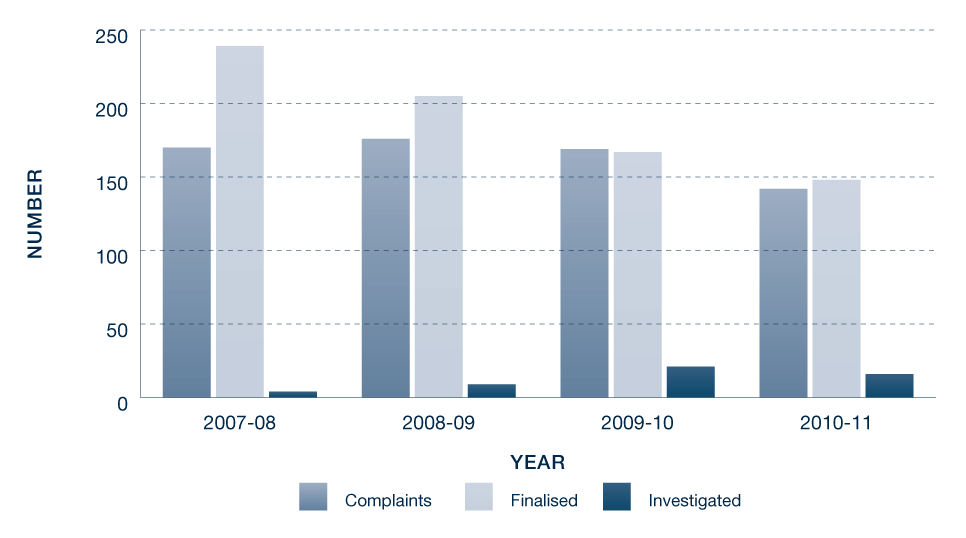

Figure 4: Approaches and complaints received, investigated and finalised about ACT Policing, 2007-08 to 2010-11

Of the 16 complaints we did investigate, the main issues raised covered use of force, misuse of authority, failure to act, discourtesy, arrest and misconduct.

We were critical of the AFP in two cases - one, where in our view, the AFP's investigation of a complaint was badly handled and another where there was an unreasonable delay (of almost 15 months) in investigating the complaint.

In relation to the badly handled complaint, we prepared a detailed report for the AFP Commissioner on what we identified as the deficiencies. Of particular concern to us were inadequately addressed conflicts of interest, incomplete and unsubstantiated information in the report of the complaint investigation and the sharing of information with third parties in the context of informal inquiries, as outlined in the case study below.

A badly handled complaint

Mr J complained to this office that the AFP officer who had investigated his complaint was the supervisor of the officer about whom he had complained. The outcome of that investigation was that Mr J's complaint was 'not established' [not substantiated]. The original complaint that Mr J had made to the AFP was that an officer had acted on unsubstantiated information to make enquiries about Mr J that had caused him embarrassment.

After we investigated Mr J's complaint we came to the view that the original officer had made an error in judgement in the actions that he had taken. However, of particular concern to us was that the AFP officer who investigated Mr J's complaint had not disclosed his involvement, as the supervisor of the officer complained about. We were of the view that this supervisor had also not properly investigated Mr J's complaint and not adequately disclosed what we considered to be his conflict of interest in conducting this investigation. The Ombudsman was sufficiently concerned about this matter, and the initial AFP response to our views, to prepare a report to the AFP Commissioner about our conclusions on the investigation and to recommend that the AFP better address conflict of interest, information sharing issues, and improve its record keeping.

The Commissioner reconsidered the case in light of the Ombudsman's comments and commissioned a review of the way that the AFP had managed the complaint and the circumstances that led to that complaint being made. The Commissioner's conclusion was that the case showed isolated issues of procedure in terms of the actions of the officer subject to the complaint and the officer who undertook the complaint investigation. However, the Commissioner was satisfied that a 'conflict of interest' was not a key factor in either the original investigation or the complaint investigation.

The Commissioner agreed to action the Ombudsman's recommendations in relation to conflict of interest and record keeping but was of the view that the AFP's information sharing practices were consistent with the relevant legislation.

Given the AFP response the Ombudsman decided not to publish the report, but he was sufficiently concerned about the way the original complaint was managed to reiterate to the Commissioner his critical findings.

The Ombudsman has continued to highlight that the importance of the AFP complaint management practices being both transparent and seen to be above reproach is fundamental to the integrity of the police in the eyes of the community. It is essential that the processes of investigation and internal review recognise that the public perception of the police can be compromised if a customer-centred approach to complaints is not taken.

For the remaining 14 complaints we investigated, we recommended in two cases that the AFP apologise to the complainant and provide a better explanation of its actions. We were able to resolve a number of complaints directly by providing a better explanation to the person concerned - for example in one case that explanation concerned watch-house procedures and the role of AFP members. And in another why the person's vehicle had been stopped by the AFP. In relation to an FOI request to the AFP, we were able to inform the complainant that their request was not received by the AFP due to a failure in the mailing system.

In one case we investigated, the complainant tried on a number of occasions to have the AFP correct its records. Its failure to do so caused him unnecessary embarrassment and stress, as illustrated below.

Complainant sees red

Mr K received a Traffic Infringement Notice (TIN) for a camera detected offence for allegedly running a red light in September 2008. He then received another red light camera TIN in February 2009. In June 2009 he wrote to the AFP disputing both TINs, stating that the photo evidence did not support the offences and requested the matters be determined by a Court. When, later that month, Mr K received a letter from the AFP withdrawing both TINs he thought the matter was closed.

In mid-2010 Mr K received a letter from the Road Transport Authority advising of the impending suspension of his licence for an unpaid fine relating to the two TINs. In July 2010 Mr K wrote to the police advising that the TINs had been withdrawn and no fines were owing. In August 2010 he received a letter from the AFP stating that only one of the TINs had been withdrawn and if the fine was not paid his licence would be suspended. In early August 2010 Mr K attended the City Police Station to show the AFP the letter withdrawing the two TINs and the AFP took copies of the letter.

In late August 2010 Mr K was stopped for a random breath test in Victoria. A routine check showed that his licence was suspended (due to the non-payment of the 'withdrawn' TINS) and he was detained. After being excused he drove back to Canberra. Later that day, he received a third TIN for a camera detected offence (speeding) for travelling at 91 km/h in an 80 km/h zone. Mr K wrote to the police asking for the TIN for speeding to be withdrawn because of his good driving record.

In early September 2010 Mr K received a letter from the AFP stating that one of the earlier red light TINs in dispute had been withdrawn, the sanction on his licence has been lifted and his licence was no longer suspended. Mr K complained to us in September 2010. In October 2010 Mr K received a letter from the AFP advising that the August 2010 speeding TIN would not be withdrawn because of the warning signs before the camera and his prior traffic infringement history in 2008 and 2009 (the disputed red light TINs) and that the matter had been referred to the Court.

As a result of our investigation the AFP acknowledged that one of the earlier TINs was not withdrawn at the time due to a clerical error by AFP staff. In our view, had the AFP actioned these matters properly, Mr K would not have been detained in Victoria and suffered the consequent embarrassment and stress from his unsuccessful attempts over two years to have the issue sorted out. We wrote to the AFP and suggested that a written apology be provided to Mr K.

Review of complaint handling

The Ombudsman has an obligation under s40XA of the AFP Act to review the administration of the AFP's handling of complaints through inspection of AFP records. This includes records of the handling of complaints about ACT Policing. The Ombudsman reports to the Commonwealth Parliament annually, commenting on the adequacy and comprehensiveness of the AFP's handling of conduct and practices issues, and inquiries ordered by the relevant Minister. Our Annual report on the Commonwealth Ombudsman's activities under Part V of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 covered the period 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2010 and was tabled in Parliament in February 2011. This report dealt with three reviews of AFP complaint records that we undertook in that period. The report is available on the Ombudsman's website (www.ombudsman.act.gov.au).

We made a number of recommendations to the AFP arising from the three reviews:

- The AFP should conduct further analysis to determine the causes of delay in finalising complaints in all categories.

- The AFP should continue to focus on improving outcome letters to complainants, providing details of findings made and the reasons for those findings.

- The AFP should give more attention to maintaining regular contact with complainants during the course of an investigation and, where a matter will not be finalised within the prescribed benchmarks, provide a report to the complainant that outlines the progress.

- The AFP should explain the complaints process clearly to the complainant and record this in their record management system (CRAMS).

- The AFP should advise the complainant they have the right to complain to the Ombudsman about the actions of AFP members and about AFP policies, practices and procedures, and advise how they can complain.

- The AFP should improve the standard of recording of information in Operational Safety Use of Force Reports, consistent with the requirements of the Commissioner Orders (CO3).

- Investigations and adjudications of complaints of excessive use of force should overtly demonstrate that the CO3 requirements of negotiation and de-escalation have been fully considered. Members using force should be required to demonstrate that they appropriately employed or discarded these strategies based upon the circumstance that were present at the incident.

- The Operational Safety Use of Force Report should be amended to include a section requiring the member to set out full details of the member's attempts to negotiate and de-escalate the situation, or to set out full details of why this was not appropriate in the circumstances.

- Complaint investigations should seek to resolve differences between the evidence of complainants and that of members, particularly for more serious conduct issues, by seeking corroborating evidence. This should include other forms of evidence such as closed circuit television (CCTV) records.

- Investigators and decision-makers should consider a member's complaint history when conducting a complaint investigation and making a decision whether or not to establish a complaint.

We noted that the AFP continued to make efforts to improve the quality and consistency of its complaint handling. In particular the standard of adjudications of serious complaints was high, however, we noted deteriorating timeliness in resolving complaints across all categories from the least to the most serious. Since then, the AFP has continued to take positive steps to address the backlog of complaints and has kept our office briefed on a variety of strategies it has employed to achieve this. We also continued to draw attention to the need for the AFP to better use the information provided by complainants to determine and address systemic problems.

A consistent finding of our recent reviews was that the rate of the AFP establishing complaints from members of the public was very low. In particular we found that no complaints from members of the public about excessive use of force had been established across all of the AFP, including the ACT, from the time that the new complaints handling regime had commenced in December 2006 up until the cut off time for our last review of complaints for the reporting period, in November 2009.

We noted that that there was little evidence on the records we looked at to show that AFP members took steps to diffuse difficult situations before resorting to force. We also saw that records were inconsistent or incomplete.

We continue to take a close interest in complaints about the AFP's use of force and have taken the opportunity to observe AFP training in this area. This assists us to better understand how policies are put into operational practice and can also help us to better understand the information we get from police when we investigate complaints. Further details on our findings and the AFP's response can be found in the most recent report to the Parliament, available on our website (www.ombudsman.gov.au).

Of the 737 conduct issues raised in complaints to the AFP during the review period 2009-10, 62% related to ACT Policing. Of all complaints received, nearly 50% are about ACT Policing. This is consistent with ACT Policing being the area of the AFP with the greatest contact with members of the public.

Of these, the AFP considered nine per cent 'established' (substantiated).

Critical incidents

The AFP notifies the Ombudsman of critical incidents involving ACT Policing. Critical incidents are incidents in which a fatality or significant injury has occurred, or where the AFP has been required to respond to an incident on a large scale, as might occur during a public demonstration. Usually we do not get involved in the investigation of critical incidents unless the AFP requests our involvement. The AFP provides a briefing to the Ombudsman so the office can keep a watching brief on the more serious incidents that arise in the ACT involving the AFP.

During 2010-11, the Ombudsman was notified of two critical incidents. One was in October 2010 where ACT police were called out to a residence to assist the ACT Domestic Animal Services in catching two large and dangerous dogs that had attacked and bitten some residents. The animal service officers were unable to catch the dogs and the police ultimately shot and killed one dog, with the other one subdued and later euthanised.

During this incident, one of the bullets ricocheted through the window of a residential address but no one was injured. We reviewed the police investigation and found no reasons to criticise the actions of the officers at that time. The police did state that they would use this incident as a case study for future training purposes.

Stakeholder engagement, outreach and education activities

The Ombudsman's office hosted the annual AFP/Ombudsman Forum in March 2011. The forum is a valuable opportunity to discuss relevant issues that arise through the work of both agencies, to exchange information and ideas on ways to improve the AFP's complaint handling processes. This year we considered the AFP Categories of Conduct which is a legislative instrument determined jointly by the AFP Commissioner and the Ombudsman under the AFP Act. It forms the basis for AFP investigations of complaints against members.

The Ombudsman Law Enforcement Team engaged in outreach and stakeholder activities during the year to discuss the role of the Ombudsman and our complaint handling procedures. This assists people to understand how they can make a complaint. Outreach during this period included:

- attending the Canberra Institute of Technology Students Association and Summernats' Fyshwick Nats 2010 car show. This annual event is held at the Fyshwick Trade Skills Centre to promote the automotive trades and encourage young people to take pride in their cars. We found that the students and apprentices often had little knowledge of our office or appreciation that they could complain about the way they were treated by the police, or any government agency. The students and apprentices were just as interested in discussing matters related to Centrelink, housing and other government agencies and bodies they interacted with. Most were surprised that they would be given an opportunity to discuss their concerns

- a presentation to staff of the Bimberi Youth Detention Centre to remind them that children or their parents who have a complaint about the AFP or other ACT agencies can contact our office

- attending the Canberra Institute of Technology International Student Orientation Day, providing a presentation and answering questions at our stall

- visiting the ACT Disability, Aged and Carer Advocacy Service.

AFP - Commonwealth and Law Enforcement Ombudsman Forum - March 2011

Looking ahead

Over the next year we will continue to focus our attention on working with the AFP to further improve its timeliness in finalising its complaint investigations. The establishment by the AFP in 2010 of an Adjudication Panel for the determination of more serious complaints, and the appointment of an independent consultant by the AFP to adjudicate on older complaints, should assist the AFP to address the delays in finalising the more serious, Category 3, complaints.

We would like to see the AFP embrace complaints from members of the public as a resource to improve their operations and interactions with the wider community. By doing so the number of future complaints should diminish, particularly where systemic issues are addressed in a timely manner.

The AFP also needs to improve the way it communicates with complainants and members of the community, particularly in explaining decisions and the outcomes of its complaint investigations.

Already the AFP has informed our office about how it intends to improve the format of letters to those complaining about less serious matters. By changing the language from whether a complaint is 'established' or 'not established' to acknowledging that a complaint has been received, will help the AFP to use that complaint to better manage the particular area of concern.

ACT Policing - Inspections

Overview

Our role

Child Sex Offenders Register

The Child Sex Offenders Register in the ACT is established by the Crimes (Child Sex Offenders) Act 2005 (ACT). The Register must contain current information relating to the identity and whereabouts of persons residing in the ACT who have been convicted of sexual offences against children.

Information on the register comes principally from offenders, who must report any changes in their circumstances such as a change of address, within seven days, and in any case must contribute details to the register or confirm existing details at least once a year.

The ACT Ombudsman is required to ensure that the Register is maintained accurately by ACT Policing. In 2010-11, we conducted one inspection of ACT Policing in relation to the Register.

Controlled Operations

The Crimes (Controlled Operations) Act 2008 allows ACT Policing to conduct controlled (covert) operations in the ACT. The Ombudsman is required to inspect the records of ACT Policing at least once every 12 months to ascertain compliance with the Act. In 2010-11, we conducted one inspection of ACT Policing in relation to its conduct of controlled operations.

Influencing positive change

Our inspections provide external scrutiny of, and hold agencies accountable for, the use of covert powers and how they deal with sensitive information. In doing so, our main focus is to improve agencies' compliance with the relevant legislative provisions. Therefore, a large part of our work is raising awareness of actual and potential compliance issues among the agencies we inspect, as well as with relevant policy makers within government. By promoting positive change in this way, we believe that agencies are more likely to collaborate in a joint approach to achieving positive results.

Another way in which we promote positive change is to ensure that our own inspection processes are open and transparent to the agencies, the responsible Ministers and Parliamentary Committees. For example, before conducting inspections we write to ACT Policing to outline our inspection process, the criteria used to assess compliance, the documents we require access to and the reasons for requesting these documents. We also pursue discussions outside the formal inspection process with agencies on administrative processes that may lead to improved compliance with the legislation.

Inspection findings

ACT Child Sex Offenders Register

Under the section 20A of the Ombudsman Act 1989 (ACT), the ACT Ombudsman may provide a written report to the Minister for Police and Emergency Services on the results of any inspections carried out and compliance with the Crimes (Child Sex Offenders) Act 2005 (ACT) by ACT Policing.

This office has conducted five inspections of the register since its introduction in 2005, with the fifth inspection of the register conducted at the time of this report in June 2011 and the report of that inspection being in the process of being finalised. The June 2010 inspection report was provided to the Minister for Police and Emergency Services and the ACT Chief Police Officer during the current reporting period. The Ombudsman found that ACT Policing is compliant with the relevant provisions of the Act and that the register is being maintained appropriately. In addition to assessing compliance, the Ombudsman made two recommendations to ACT Policing in relation to improving certain processes regarding controlling access to the register and restricting information about protected witnesses.

We acknowledge ACT Policing's cooperation with Ombudsman staff during inspections. ACT Policing continues to display a willingness to implement both suggestions for improvement and formal recommendations made by the office.

ACT Controlled Operations

Under the Annual Reports (Government Agencies) Act 2004 , the ACT Ombudsman is required to report every financial year on the results of each inspection conducted under the Crimes (Controlled Operations) Act 2008 . The report must include a report on the comprehensiveness and adequacy of the records of the agency and the cooperation given by the agency in facilitating the inspection by the ombudsman of those records.

We conducted one inspection during 2010-11, which examined ACT Policing's records associated with authorities to conduct controlled operations that had either expired or were cancelled during the period 16 October 2009 to 30 June 2010. ACT Policing was assessed as compliant with the requirements of the Crimes (Controlled Operations) Act 2008 .

We appreciate ACT Policing's cooperation with Ombudsman staff and the provision of documents relevant to the inspection. The ACT Policing was also open to suggestions for improvement, and preparedness to implement recommendations.

Improvements made by ACT Policing

ACT Policing has a high standard of recordkeeping associated with the conduct of controlled operations. In particular, we noted improvements made by ACT Policing in relation to including details about a controlled operation in its "principal law enforcement officers' reports" under s 27(1) of the Crimes (Controlled Operations) Act 2008.

Issues noted

The Crimes (Controlled Operations) Act 2008 gives participants in a controlled operation protection from criminal responsibility and civil liability for their actions. As such, it is important for participants of a controlled operation to ensure they act within the terms of the controlled operations authority.

In one instance, a controlled operation commenced an hour prior to the authority to conduct the operation being issued. Due to the nature of the operation, we were advised that the authority was unable to be secured in time and the participants commenced the operation without the authority in place. Accordingly, the participants in the controlled operation were not protected from criminal and civil liability. This occurrence was self-disclosed by ACT Policing at the time of the inspection.

ACT Policing was not aware that it could obtain verbal approval for the controlled operation, which would ensure that the authority was granted on time. Accordingly, we advised that procedures for making an urgent application to conduct a controlled operation are available under the Act. We made the following recommendation:

- ACT Policing should ensure that the conduct authorised by a controlled operation authority is performed within the period that the authority is in force, as participants engaging in any conduct falling outside the period of the authority may not be protected from criminal responsibility under s 18 or civil liability under s 19 of the Crimes (Controlled Operations) Act 2008 .

Stakeholder Engagement

Working with ACT Policing

Throughout 2010-11, we worked closely with ACT Policing to improve compliance with the administration of the Child Sex Offenders Register and the conduct of controlled operations and achieved positive results with both.

In relation to the administration of the Child Sex Offenders Register, ACT Policing has improved communication with the ACT courts and interstate police forces so that the Register captured the most up-to-date information on offenders.

In relation to controlled operations, ACT Policing self-disclosed a non-compliance issue at the inspection and undertook to improve its processes to ensure that the situation does not arise again. ACT Policing was open to our suggestions for improvement and willing to accept advice.

Working with the ACT Government