A report on the operation of the Freedom of Information Act 2016 for 2021-22

Introduction from ACT Ombudsman

We are pleased to introduce the 2021–22 annual report prepared under s 67 of the Freedom of Information Act 2016 (ACT) (FOI Act).

In presenting this report, I (Iain) would like to acknowledge the work of Penny McKay as Acting Ombudsman from 1 August 2021 to 31 July 2022. Under her leadership, the Office of the ACT Ombudsman (the Office) continued to promote the pro-disclosure objects of the FOI Act, working closely with agencies to ensure consistent and timely decision-making.

It was a great privilege and pleasure to be appointed Ombudsman on 1 August 2022 for a 5‑year term. I have a deep interest in the role and contribution of the Ombudsman. One measure of a fair and equal society is that people can raise concerns about the actions of government agencies with an independent body such as the Ombudsman that can investigate those concerns.

Transparency and openness instil confidence and trust in decision‑making and help the community understand why difficult decisions are made. The ongoing impact of COVID‑19 on the ACT community highlights the importance of allowing access to government information during times of crisis. More than ever, government decision-makers must ensure they are creating and maintaining records of their decisions and wherever possible making that information available to the public.

During 2021–22, the Office again felt the impact of COVID-19. We adjusted the way we work – including through use of technology and virtual solutions – and continued to deliver the Office’s functions. We engaged with agencies to share better practices and provide guidance on dealing with complex issues.

In February 2022, the Office hosted its first virtual FOI practitioners’ forum. It was a great opportunity for more than 30 Information Officers and FOI staff from ACT government agencies to come together after a lengthy period working remotely during 2020 and 2021. Further, all 9 ACT government directorates provided both mandatory and optional data for the Office’s reporting, allowing the Office to build its understanding of the operation of the FOI Act.

This year the Office completed 30 Ombudsman reviews, of which 18 resulted in formal decisions published on our website and AustLII. The other 12 were resolved without the need for a formal decision. The 85 Ombudsman review decisions published as of 30 June 2022 contribute to a growing body of guidance on the FOI Act to assist practitioners with future decision-making.

The Office will continue working closely with agencies to improve the operation of the FOI Act in the ACT, with a view to ensuring consistent and timely decision-making in accordance with the legislation’s pro-disclosure objectives. In the coming year, the Office will also focus on providing education and information about Open Access requirements, and guiding agencies to improve their compliance.

I would like to thank all the staff in the Office of the ACT Ombudsman, and our stakeholders in the ACT Government, for their work to promote openness and transparency.

|

|

Iain Anderson ACT Ombudsman | Penny McKay Acting Ombudsman (1 Aug 21 – 31 Jul 22) |

CONTENTS

- Part 1:INTRODUCTION

- Part 2: OPEN ACCESS INFORMATION DECISIONS

- Part 3: INFORMAL REQUESTS FOR INFORMATION

- Part 4: ACCESS APPLICATIONS

- Part 5: AMENDMENT OF PERSONAL INFORMATION

- Part 6: OMBUDSMAN REVIEWS

- Part 7: COMPLAINTS

- Part 8: THE YEAR IN REVIEW

- Part 9: THE YEAR AHEAD

- Part 10: GLOSSARY

Download the PDF of the report

Part 1: INTRODUCTION

This report outlines the ACT Ombudsman’s insights about the operation of FOI Act in 2021–22, as well as planned priority activities for 2022–23.

The public’s right to access government information, underpinned by properly administered FOI legislation, is essential for the working of representative democracy. The FOI Act in the ACT has a pro‑disclosure bias and a focus on making government information accessible to the public.

Under the FOI Act every person has a right to access information held by the government, where it is not contrary to the public interest for that information to be disclosed.[1]

The FOI Act requires agencies and Ministers to publish government information proactively and be transparent about the information they do not publish. This includes information held by government directorates and agencies, ministers, government owned corporations (with some exceptions), public hospitals and health services, public authorities and public universities enacted under ACT laws.[2]

The FOI Act emphasises access to government information through informal requests without the need for formal processes. Where a formal process is required, an access application can be made under the FOI Act to the relevant agency and decisions are focused on public interest considerations.

The ACT Ombudsman oversees the FOI Act and promotes its objects by:

- conducting merits reviews (Ombudsman review) of FOI decisions

- considering requests to grant extensions of time to decide access applications

- monitoring the operation of the FOI Act, including the publication of Open Access information by agencies and Ministers, and agency compliance with the FOI Act

- making open access information declarations

- publishing guidelines which are to be periodically revised

- investigating complaints about an agency or Ministers’ action in relation to their functions under the FOI Act.

Information on the Ombudsman's own performance under the FOI Act, as an ACT government entity required to report under s 96 of the FOI Act, is included in the ACT Ombudsman’s Annual Report

2021–22, which is available on our website.[3]

Part 2: OPEN ACCESS INFORMATION DECISIONS

The intention of the FOI Act is to make government-held information accessible. Formal access applications for information should be a last resort, with information being published proactively wherever possible.[4] ACT government agencies must publish certain information routinely without the need for a formal application to be made by a member of the public. This includes policy documents, reports, budget papers and agency disclosure logs.[5]

The ACT Government maintains an Open Access portal (act.gov.au/open-access) to provide the public with a central, searchable interface to access government information. Agencies can publish information on their own website and add a link to this information on the portal.

In June 2020, the Ombudsman finalised its Open Access Guidelines (ombudsman.act.gov.au/publications/foi-guidelines). These guidelines are notifiable instruments available on the ACT Legislation Register[6] and on the Ombudsman’s website.[7] The guidelines help ACT agencies to understand and meet their Open Access obligations.

The Office’s own Open Access Strategy (ombudsman.act.gov.au/publications/act-ombudsman-policies-and-protocols) is available online[8] and sets out:

- what information will be made publicly available

- how it will be made available

- how published information will be reviewed to ensure it remains accurate, up to date and complete

- that we will publish our reasons for decisions when information may not be made publicly available because it is contrary to public interest.

The strategy supports the Office’s staff to comply with Open Access requirements and may be used to assist directorates and agencies to develop their own strategies.

This year the Ombudsman continued monitoring ACT agencies’ compliance with their Open Access obligations under Part 4 of the FOI Act.

Decisions to publish

During the reporting period, agencies and Ministers continued to publish Open Access information on their respective websites and on the Open Access portal.

A total of 2,143 decisions to publish were made. This is an increase on the 1,688 decisions published in 2020–21, demonstrating agencies continue to take their Open Access obligations seriously and proactively publish Open Access information.

The Ombudsman recognises the above figures reflect agency decisions to publish information:

- on the agency disclosure log

- registered on the Open Access website, or

- on the agency

We recognise this may not capture all the information published by agencies. Agencies are not expected to keep formal records or make public interest assessments on the multitude of documents they publish on a daily or weekly basis. To require this would impose an unnecessary administrative burden and could potentially undermine the objectives of the FOI Act by discouraging agencies from publishing government information.

Decisions not to publish

Generally, if Open Access information is not made available because it is contrary to the public interest information, the FOI Act requires the agency instead to publish a description of the information and the reason for this nondisclosure, except in limited circumstances.

In 2021–22, ACT government agencies made 278 decisions not to publish Open Access information, compared to 83 decisions in 2020‑21.

At first glance, this may appear to suggest an increase in the behaviour of agencies withholding information. However, the Office considers this increase actually reflects the continuing development and maturity of agencies’ Open Access strategies, as agencies are considering a wide range of information before deciding not to publish some information. By contrast, a much lower number of decisions not to publish Open Access information might indicate that agencies simply do not turn their minds to publishing information.

In 2020–21, the number of decisions not to publish a description of the information declined, with 5 such decisions made in 2021–22, compared to 11 such decisions made in 2020–21.

Decisions by Agencies and Ministers

The number of Open Access decisions made by each of the agencies and Ministers, as reported to the Ombudsman, are outlined in Figure 1.[9]

The Office of the Legislative Assembly (OLA) made the highest number of decisions to publish Open Access information, with 792 decisions, followed by the Chief Minister, Treasury and Economic Development Directorate (CMTEDD), with 633 decisions.

Most agencies did not make any formal decisions to withhold information.

In 2021–22, a total of 33 decisions were made to publish Ministerial information, including 27 Ministerial diaries, 4 Ministerial travel reports, and 2 Ministerial hospitality reports. This is a slight decrease from the 39 decisions made in 2020–21, which is not unexpected considering the impact of COVID-19 restrictions, particularly on travel and lockdowns.

Figure 1: Open Access decisions by agencies that reported decisions

Directorates and agencies | Decisions to publish Open Access information | Decisions not to publish Open Access information | Decisions not to publish a description of Open Access information |

|---|---|---|---|

Office of the Legislative Assembly | 792 | 0 | 0 |

Chief Minister, Treasury, and Economic Development Directorate | 633 | 240 | 4 |

Canberra Health Services | 255 | 36 | 0 |

Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate | 130 | 0 | 1 |

Justice and Community Safety Directorate | 88 | 0 | 0 |

ACT Health Directorate | 77 | 2 | 0 |

Major Projects Canberra | 50 | 0 | 0 |

ACT Ministers | 33 | 0 | 0 |

Canberra Institute of Technology | 26 | 0 | 0 |

ACT Audit Office | 12 | 0 | 0 |

ACT Ombudsman | 12 | 0 | 0 |

Education Directorate | 10 | 0 | 0 |

Cultural Facilities Corporation | 7 | 0 | 0 |

Electoral Commission | 7 | 0 | 0 |

Suburban Land Agency | 6 | 0 | 0 |

Community Services Directorate | 2 | 0 | 0 |

City Renewal Authority | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Human Rights Commission | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Transport Canberra and City Services | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Total | 2,143 | 278 | 5 |

Part 3: INFORMAL REQUESTS FOR INFORMATION

Information can be requested informally from an agency or Minister, which may decide to release it directly without the need for a formal access application.

Agencies are not required to report on the number of informal requests received, or related outcomes, as to do so would impose an unnecessary administrative burden. Directorates and agencies did, however, report that over the period 214 formal access applications were withdrawn, which is an increase compared to the 130 withdrawn in 2020–21.

The figures for 2021–22 also show an increase in the number of access applications resolved informally, with 84 access applications resolved outside of the formal FOI process, compared to the 52 access applications resolved outside of the formal FOI process in 2020–21.

While we cannot ascertain if all the matters resolved informally were finalised after information was provided informally, it is positive to see more applications are being resolved outside of the formal FOI process as intended by the FOI Act.

The Ombudsman encourages agencies to release information informally where possible, rather than require applicants to seek information through the FOI process. We will continue to monitor what is being reported by agencies to identify trends or issues.

Part 4: ACCESS APPLICATIONS

An access application is the formal way to request information under the FOI Act. Access applications can be made to an agency or Minister and may be reviewed by the Ombudsman. An agency or Minister will assess the application and may decide to give full or partial access to government information sought under the FOI Act, or refuse access.

An agency or Minister can refuse access to information in circumstances where it is assessed as contrary to public interest information. They can also refuse to deal with an access application or refuse to confirm or deny that information is held in limited circumstances.[10]

Applications made

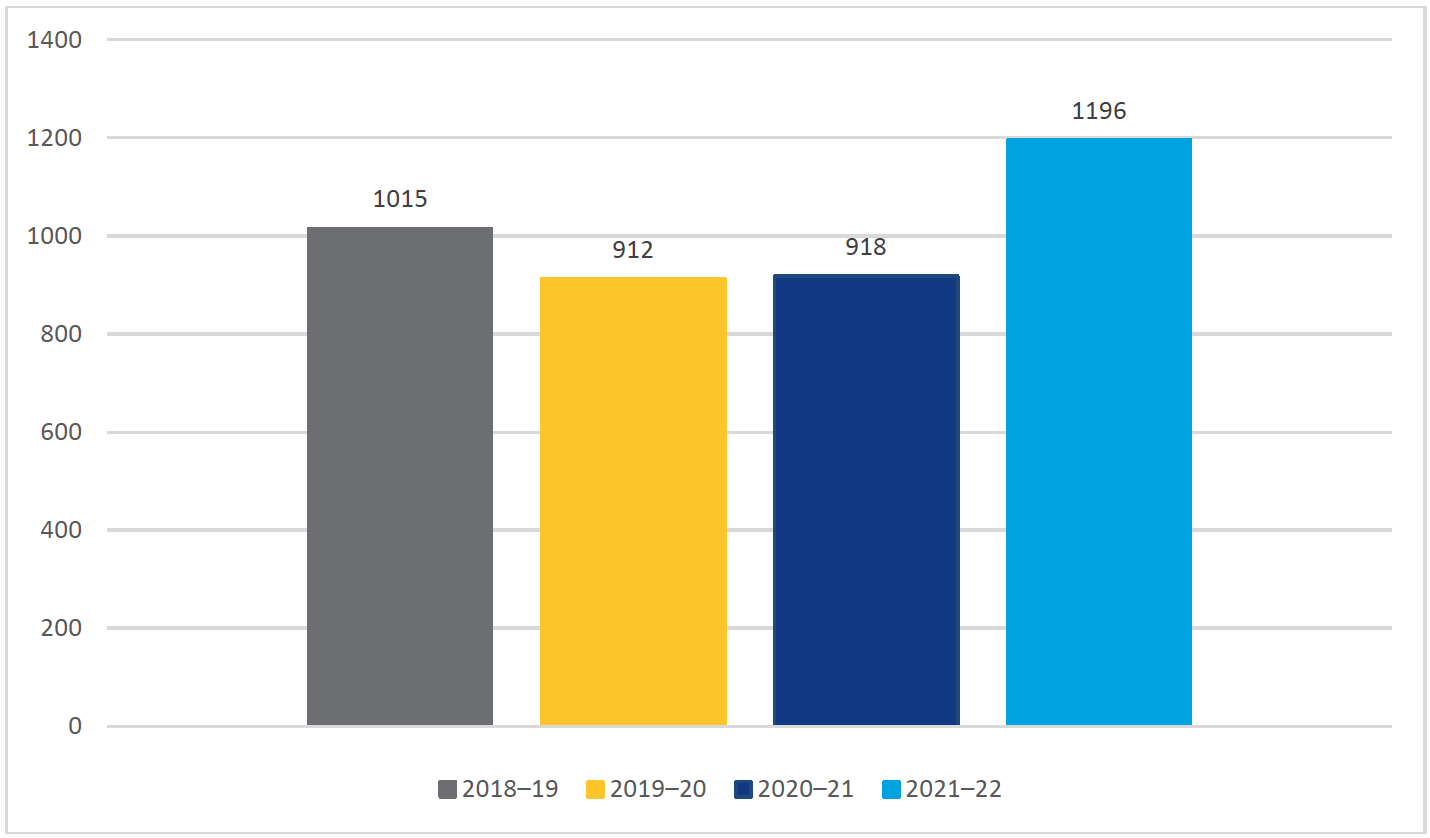

In 2021–22, 1,196 access applications were made to ACT Government agencies and Ministers.

As shown in Figure 2, this is a 30 per cent increase from the 918 access applications received in 2020–21. Figure 2 also shows the total access applications received in each financial year since 2018–19 (the first full year of the operation of the FOI Act).

Figure 2: Access applications received by agencies and Ministers

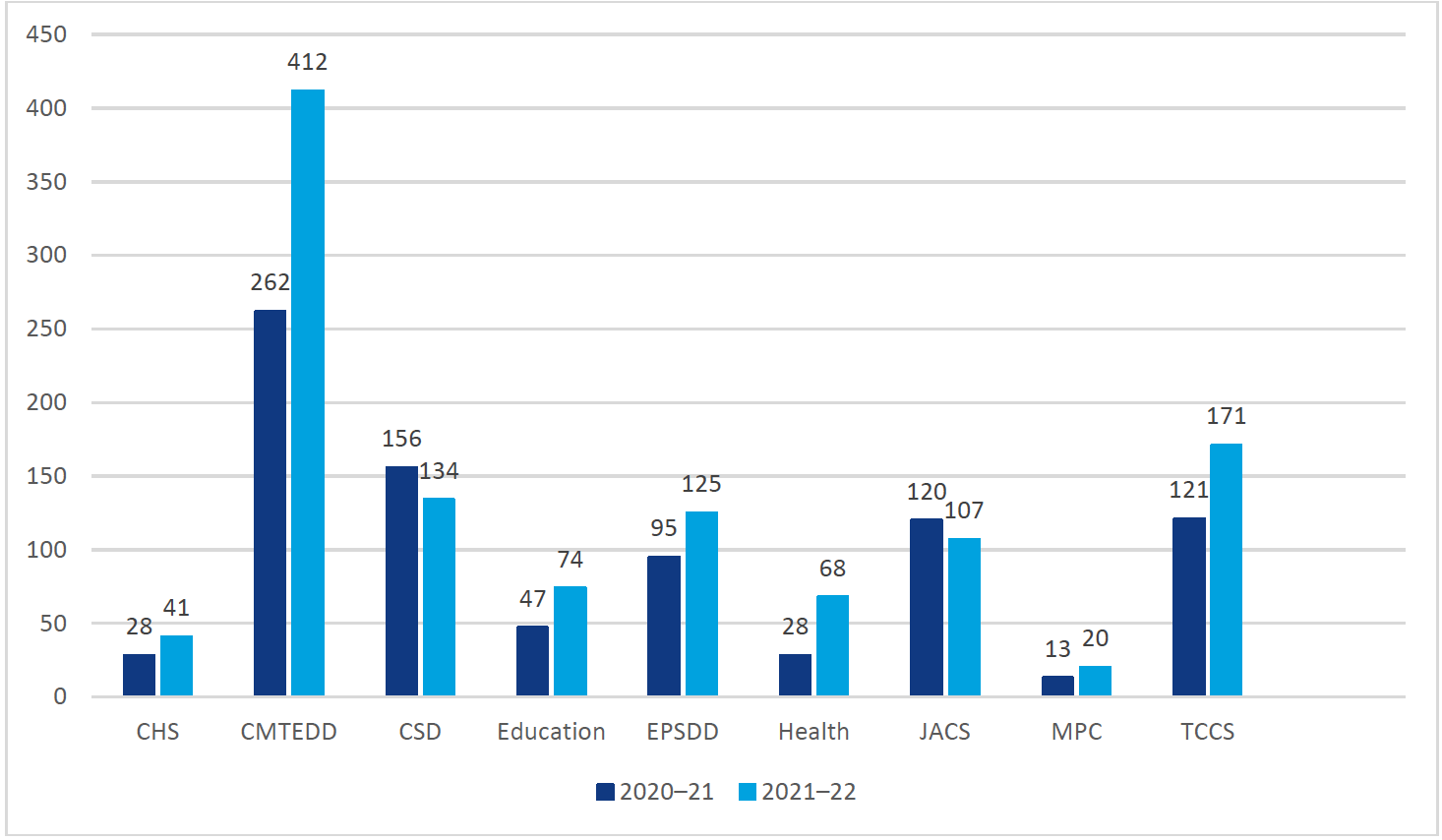

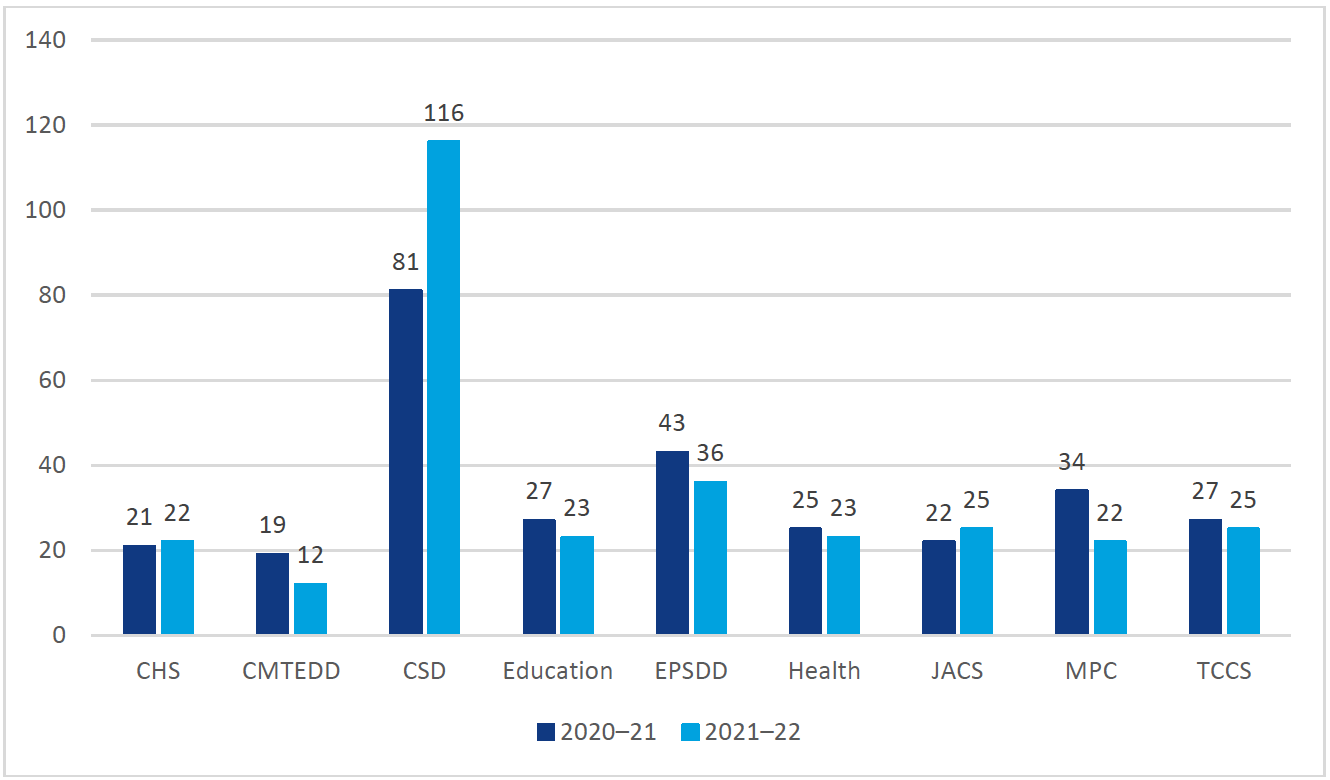

Figure 3 reflects the number of access applications received by the 9 directorates in 2021–22. The number of access applications received by the 9 directorates does not include access applications received by smaller agencies, and access applications received by Ministers.

Figure 3: Access applications received by each directorate

Application outcomes

During the reporting period, agencies, and Ministers made 978 decisions on access applications. This is a 52 per cent increase from the previous financial year when 643 such decisions were made.

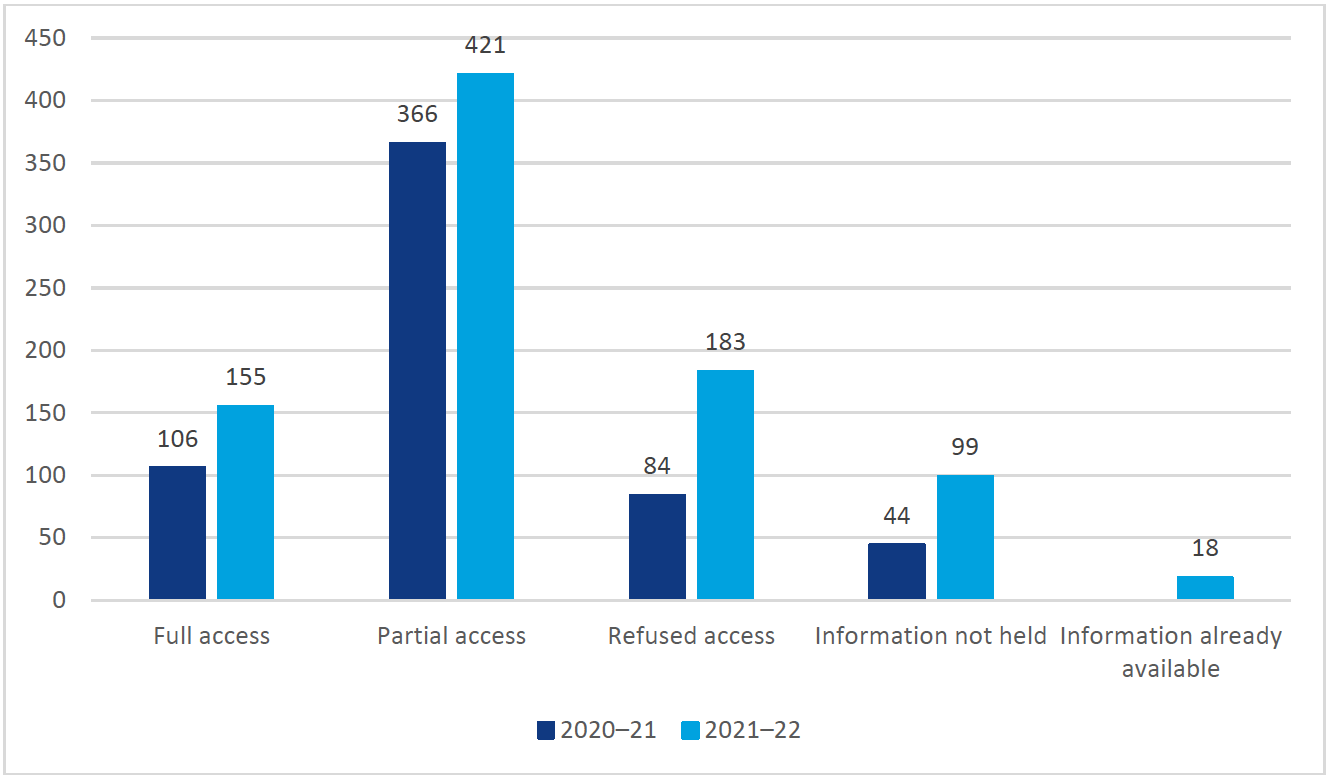

As outlined at Figure 4, of the 978 decisions on access applications reported by agencies and Ministers:

- Full access was granted in 155 decisions (16 per cent) – with the agency disclosing all information identified within the scope of the access

- Partial access was granted in 421 decisions (43 per cent) – with some information redacted prior to the release because it was assessed as contrary to the public interest information.

- Access was refused in 183 decisions (19 per cent) – with the agency deciding the information was contrary to the public interest information.

- Information was assessed as not being held by the agency in 99 decisions (10 per cent) – with an agency required to take reasonable steps to identify all government information within the scope of the application prior to determining that it cannot be located or does not

- Information was assessed as already available to the applicant in 18 decisions (2 per cent).

These figures show the proportion of decisions to grant full access has remained consistent, with full access granted in 17 per cent of decisions in 2020–21, compared to 16 per cent in 2021–22.

The proportion of decisions to refuse access has increased from 13 per cent in 2020–21 to 19 per cent in 2021–22.

The proportion of decisions to partially release information has decreased from 57 per cent in 2020–21 to 43 per cent in 2021–22.

The Office notes the combination of an increase in refusal decisions, and decrease in partial release decisions, during the reporting period. It would be premature to interpret the data as indicating a trend away from a pro-disclosure culture. The Office will continue to monitor data on these decisions closely in 2022–23.

The Office also notes, as outlined further below, one of the reasons given by agencies for the large proportion of partial release decisions is the fact that many decisions require agencies to redact small amounts of personal information. This resulted in what would otherwise be full access decisions becoming partial access decisions.

Figure 4 does not include the remaining 102 decisions (10 per cent) that were decided in different ways, such as agencies refusing to deal with the application or refusing to confirm or deny that information was held. Providing detailed data to the Ombudsman on this category of decisions is optional. We may consider making this data mandatory in 2022–23 to provide a more complete picture of decisions by agencies.

Figure 4 also excludes the 214 access applications that agencies reported were withdrawn by the applicant before a decision was made by the agency, and the 111 access applications that were reported as transferred from one agency to another to deal with.

Figure 4 includes the 18 decisions where the agency determined the information was already available to the applicant. We did not report on this data in 2020–21.

Our analysis of freedom of information data from other jurisdictions for 2020–21 indicates applicants in Australia are more likely to be granted partial access than full access.[11] This is consistent with 2021–22 data for the ACT, where the proportion of full access decisions (16 per cent) was significantly less than the proportion of partial access decisions (43 per cent).

Agencies have noted the proportion of partial access decisions is inflated by the large number of decisions where agencies make minor redactions to exclude personal information (such as personal telephone numbers or other direct contact information). This is consistent with the fact that the most common ground relied upon by agencies to withhold information under Schedule 2 of the FOI Act is that the redacted information may prejudice the protection of an individual’s right to privacy or any other right under the Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT) (Human Rights Act).

We suggest the high proportion of partial access decisions in 2021–22 indicates an opportunity for agencies to improve their initial scoping activities with applicants, for example, to seek the applicant’s agreement to exclude irrelevant information such as inconsequential personal information.

The Ombudsman will continue to monitor this issue in 2022–23.

Figure 4: Outcomes of decided access applications

Reasons for refusal

In this reporting period all directorates provided data about the reasons for refusing access to information in full or in part.

In 2021–22, the top 3 grounds relied on by agencies to withhold information under Schedule 1 of the FOI Act were:

- information disclosure of which is prohibited by law (Schedule 1, section 1.3), which was used in 62 decisions (30 per cent)

- Cabinet information (Schedule 1, section 1.6), which was used in 51 decisions (25 per cent)

- information subject to legal professional privilege (Schedule 1, section 1.2), which was used in 43 decisions (21 per cent).

This reflects a small change when compared to the top 3 Schedule 1 grounds relied on by agencies in 2020–21, with Cabinet information (Schedule 1, section 1.6) replacing law enforcement or public safety information (Schedule 1, section 1.14) in the top 3.

In 2021–22, the top 3 factors favouring non‑disclosure relied on by agencies to withhold information under Schedule 2 of the FOI Act were:

- prejudice the protection of an individual’s right to privacy or any other right under the Human Rights Act (Schedule 2, section 2.2(a)(ii)), which was used in 395 decisions (57 per cent)

- prejudice trade secrets, business affairs or research of an agency or person (Schedule 2, section 2.2(a)(xi)), which was used in 103 decisions (15 per cent)

- prejudice an agency’s ability to gain confidential information (Schedule 2, section 2.2(a)(xii), which was used in 69 decisions (10 per cent).

This is consistent with 2020–21, where the same top 3 Schedule 2 factors were reported.

We will continue to monitor these data in future years to identify trends and compare grounds and factors arising in decisions subject to Ombudsman review.

Processing times

Under the FOI Act, an access application must be decided within 20 working days, unless an applicant agrees to an extension of time, an extension is granted by the Ombudsman, or a third party must be consulted. Where a third party must be consulted, agencies have an additional 15 working days to decide the access application.

Agencies can seek an applicant’s agreement to an extension of time for up to 12 months from the date of the application. An extension beyond 12 months must be sought from the Ombudsman. If an applicant refuses an extension request, the agency can also seek an extension from the Ombudsman.

Figure 5 below shows the average processing times, in working days, by each directorate, compared to the average processing times in 2020–21.

Figure 5: Average processing time in working days by each directorate

Access applications processed within time

During the reporting period, 96 per cent of decisions on access applications were decided within the statutory timeframes – that is, within the standard timeframe or where an extension was granted by the applicant or the Ombudsman.

Access applications decided without any extension of time accounted for 69 per cent of decisions. A further 26 per cent of applications were processed where the applicant approved an extension request. Applications processed with an Ombudsman extension of time accounted for less than one per cent of decisions. The remaining one per cent of access applications became deemed refusal decisions and are discussed below.

There were 181 access applications ‘on hand’ at the end of the reporting period. However, the Ombudsman does not have visibility over the length of time these applications have been open.

Extensions of time by the Ombudsman

The Ombudsman has discretion to grant an extension of time to an agency to decide an access application. An extension can be granted if the Ombudsman believes it is not reasonably possible for the access application to be dealt with within the timeframe, because the application:

- involves dealing with a large volume of information

- is complex, or

- other exceptional circumstances

There is no cap on the length of time the Ombudsman can grant an extension and the FOI Act allows the Ombudsman to impose conditions to the extension granted. Once granted, the Ombudsman can cancel or amend the extension if the directorate does not comply with the conditions imposed.

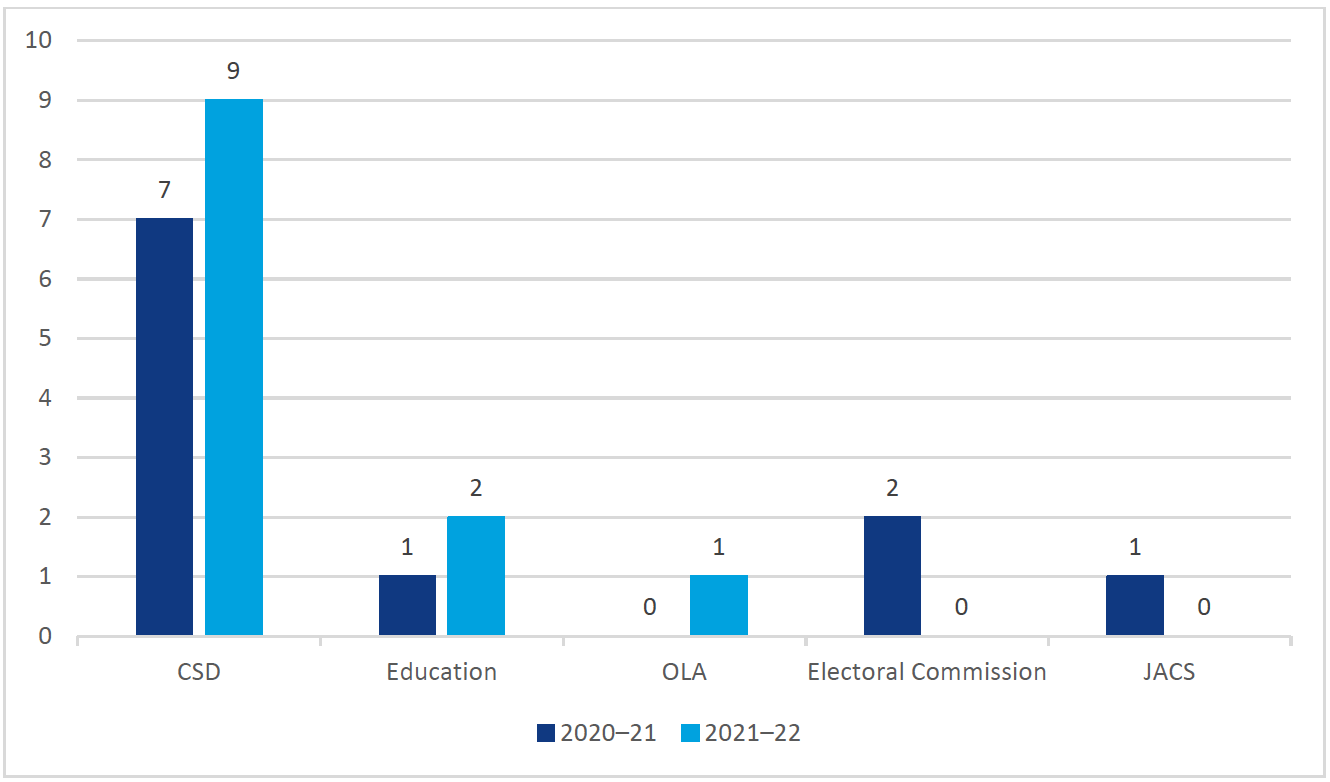

During the reporting period 12 applications were made to the Ombudsman for an extension of time. The applications made by agencies are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Extension of time applications to the Ombudsman

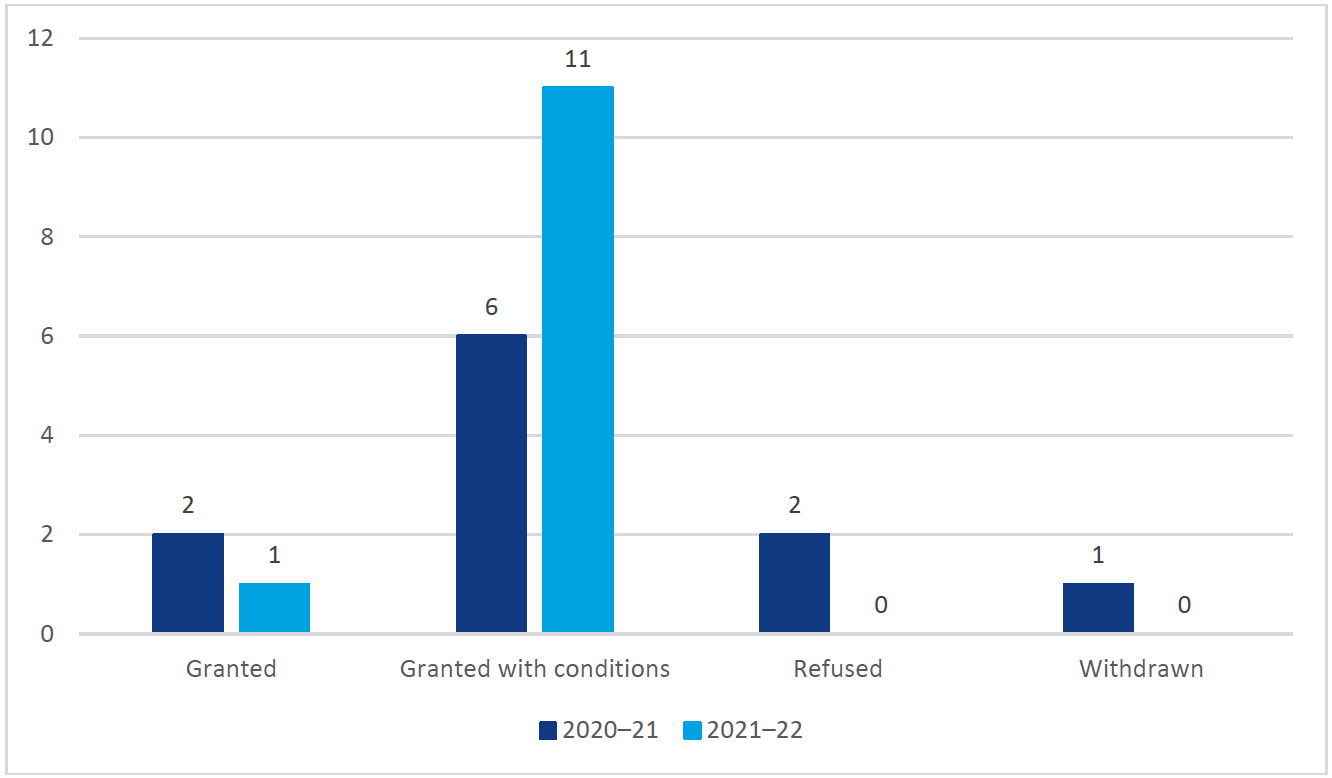

As shown in Figure 7, after assessing these requests, the Ombudsman granted all 12 applications. The Ombudsman imposed additional conditions on 11 of the 12 applications. These conditions required incremental releases of information throughout the processing period.

The length of additional time requested and granted varied. The extension granted to OLA was for 63 working days. The Education Directorate (Education) was granted extensions for 10 and 51 working days, respectively. The Community Services Directorate (CSD) requested longer extensions, ranging from 59 to 707 working days.

The lengthier extensions requested by CSD reflect the complexity and sensitivity of the access applications received by CSD, as well as the large volume of, most often, personal information sought. The long extensions requested by CSD are tempered with the incremental release of information throughout the processing period, so that applicants are not waiting the full extension period to receive all of the information requested.

Figure 7: Extension of time outcomes

Deemed refusal decisions

Where statutory timeframes have not been met and an extension of time has not been obtained, an agency or Minister’s decision is taken (deemed) to be a refusal to give access to the government information requested.

The FOI Act requires agencies to notify the Ombudsman of a deemed refusal and table a copy of the notice in the Legislative Assembly. This enables applicants to apply for Ombudsman review. Most agencies continue to process an access application and make a formal decision in deemed refusal cases, despite the statutory timeframe having expired.

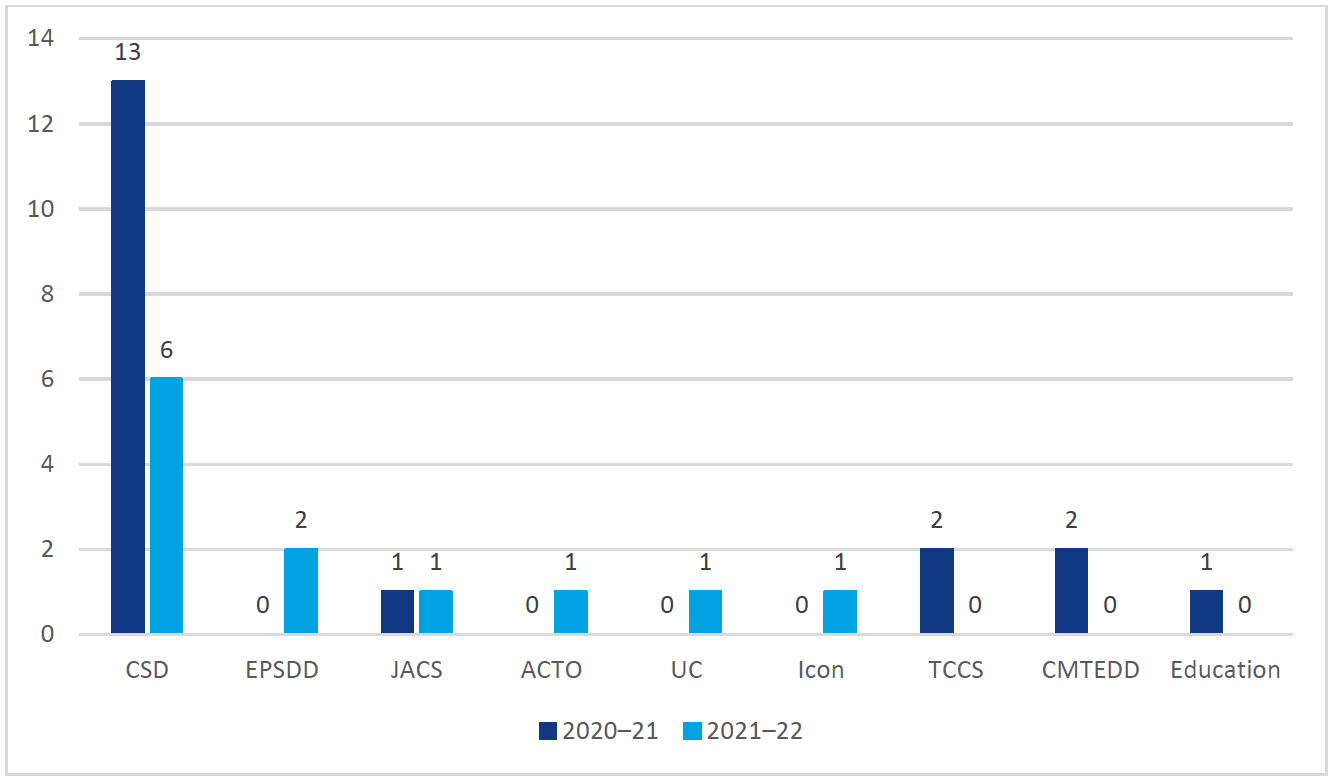

As shown in Figure 8, during 2021–22 agencies made 12 deemed refusal decisions. This is a marked decrease compared to 2020–21, when agencies made 19 deemed refusal decisions.

The Ombudsman was formally notified of 8 deemed refusal decisions. The Office identified an additional 4 deemed refusal decisions during collection of data for this report. While s 39 of the FOI Act does not specify when agencies must notify the Ombudsman of a deemed refusal, the Office considers it is better practice for agencies to give notice as soon as practicable after a deemed refusal occurs, particularly given this is a reviewable decision.

The Office has engaged with the agencies that did not formally notify the Ombudsman of deemed refusal decisions to remind them of their obligations under the FOI Act and offer assistance.

The Office’s published FOI Guidelines (ombudsman.act.gov.au/publications/foi-guidelines) provide details about these reporting requirements and draft templates to assist agencies.

Figure 8: Deemed refusal decisions

Refusing to deal with access applications

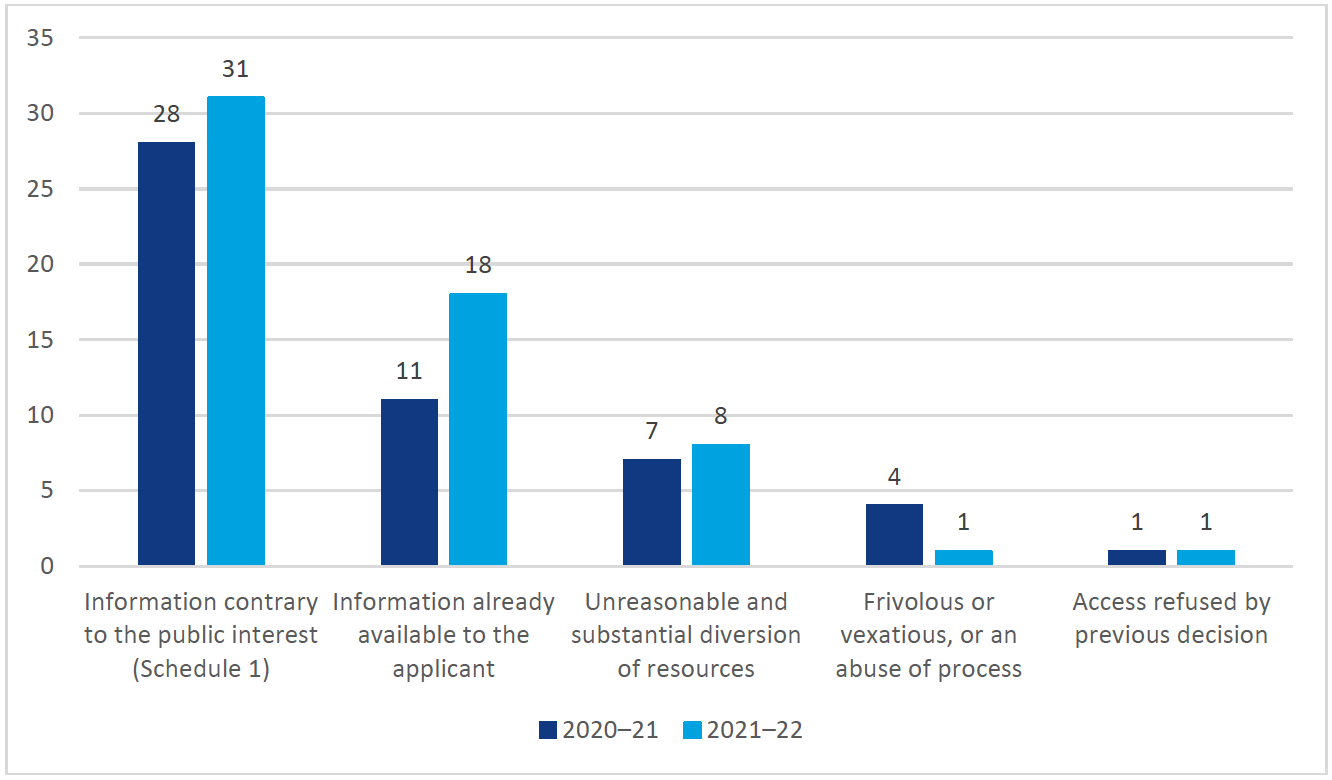

Under s 43 of the FOI Act, agencies can refuse to deal with an access application in limited circumstances.

In 2021–22, 7 agencies reported they relied on this provision to refuse to deal with access applications: CMTEDD, CSD, Education, the Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate (EPSDD), the Justice and Community Safety Directorate (JACS), OLA and the Transport Canberra and City Services Directorate (TCCS). This is a decrease on the 11 agencies that reported they relied on s 43 in 2020–21.

Figure 9 shows the reasons decision-makers decided not to deal with an access application, the most common being that the information sought is taken to be contrary to the public interest to disclose under Schedule 1 of the FOI Act (53 per cent), followed by information that is already available to the applicant (31 per cent).

Compared with 2020–21, there was a small decrease in the percentage of access applications refused on the basis that the information sought is taken to be contrary to the public interest information under Schedule 1 (56 per cent in 2020–21) and an increase in the percentage of applications refused because the information was already available to the applicant (22 per cent in 2020–21).

Figure 9: Reasons for refusing to deal with an access application

Fees

The objects of the FOI Act outline that access should be granted at the lowest reasonable cost to applicants. A fee may be charged when more than 50 pages of information are provided in response to an access application, except in certain circumstances – for example, where an access application for personal information about the applicant is made.

The fees that can be charged – where considered appropriate – are determined by the

Attorney-General and are outlined in the Freedom of Information (Fees) Determination 2018 (ACT).[12]

A single charge for processing an access application was reported by CSD in 2021–22. This is an increase from 2020–21, where no agency reported charging fees. The data is consistent with the pro-disclosure objects of the FOI Act, with cost not being an obstacle to access.

Part 5: AMENDMENT OF PERSONAL INFORMATION

If an individual has access to an ACT Government record or file or other government held information that contains their own personal information, and they believe their information is incomplete, incorrect, out of date or misleading, they can request this information be amended.

In this reporting period no formal applications were made to amend or annotate personal information under the FOI Act. This is consistent with 2020–21, where no such formal applications were made.

We understand ACT agencies generally manage such requests for amendment through other informal channels, rather than the FOI Act.

Part 6: OMBUDSMAN REVIEWS

The Ombudsman may conduct independent merits review of decisions on access applications made by agencies and Ministers under the FOI Act. In reviewing a decision, the Ombudsman can confirm or vary the original decision or set it aside and substitute a new decision. Ombudsman review decisions may be reviewed by the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal (ACAT).

Applications received

During the reporting period, the Office received 26 applications for Ombudsman review – 17 fewer than the 43 received in 2020–21.

Types of review applicants

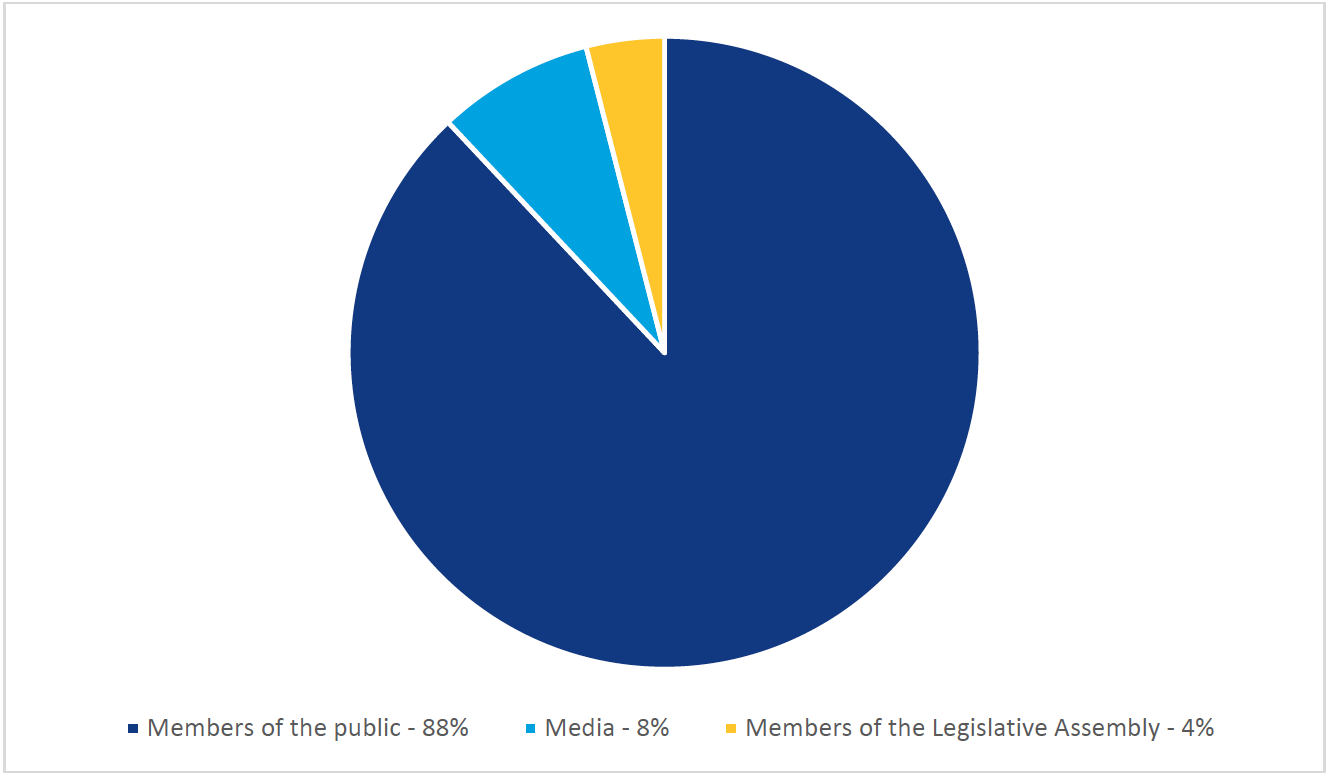

Figure 10 shows most Ombudsman review applications received in 2021–22 were made by members of the public (88 per cent), followed by the media (8 per cent) and members of the Legislative Assembly (4 per cent). The Office did not receive any review applications from private sector businesses in 2021–22.

The figures show some minor differences to 2020–21, when most Ombudsman review applications were made by members of the public (75 per cent), followed by the media (9 per cent), private sector businesses (9 per cent), members of the Legislative Assembly (5 per cent), and other applicants (2 per cent).

Figure 10: Who applied for review

Agency participation in reviews

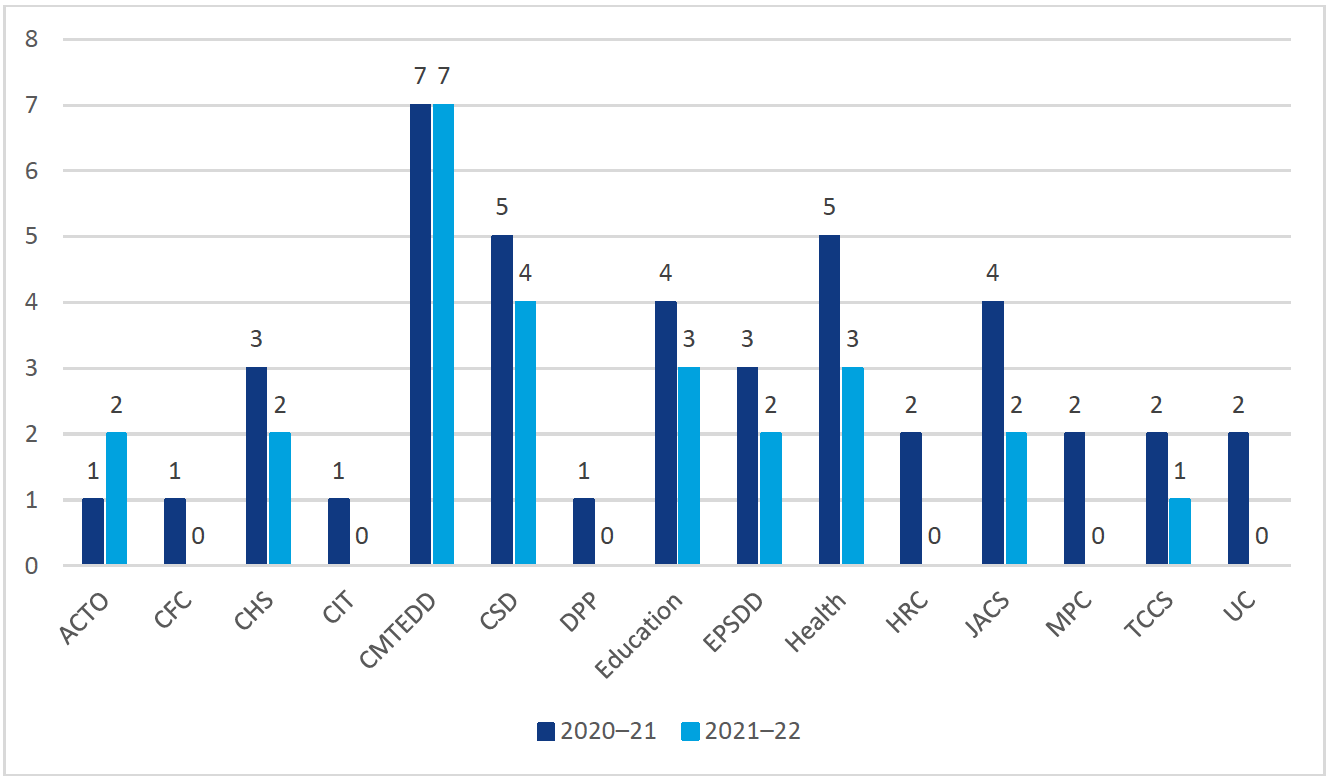

Figure 11 shows the Ombudsman review applications received in 2021–22 (and 2020–21 for comparison), broken down by agency.

The data reflects that Ombudsman review applications remained steady or decreased for most agencies.

Figure 11: Review applications by ACT agency

Applications finalised

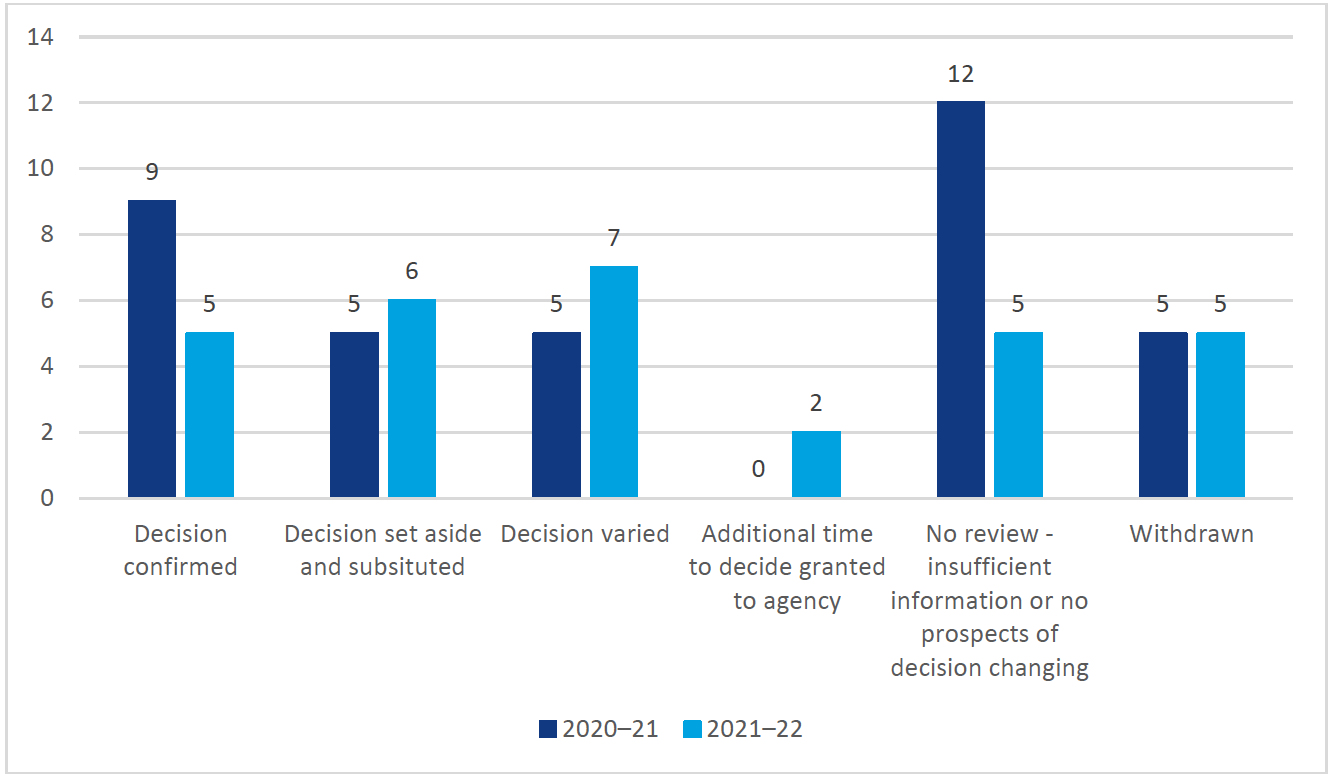

As shown in Figure 12, during the reporting period 30 Ombudsman reviews were finalised:

- 5 were withdrawn following informal resolution processes

- 18 were resolved with a formal decision

- 7 were closed with no review, of which:

- 2 were closed on the ground there was no reasonable prospect that the original decision would be varied or set aside (s 82(5)(b))

- 2 were deemed refusals for which additional time to decide was granted to the agency, which subsequently decided the matter (s 82(5)(c))

- 1 was closed after the agency subsequently decided to release information (s 82(5)(c))

- 1 was closed on the ground the application had insufficient information to conduct a review (s 82(5)(a)), and

- 1 was closed because the Office was unable to contact the applicant despite making reasonable efforts (s 82(5)(e)).

These outcomes are explained below.

The number of review matters withdrawn in 2020–21 and 2021–22 has remained steady, with 5 matters withdrawn in each year. The number of formal decisions has remained consistent, with 19 formal decisions made in the previous year compared to 18 made in the current reporting period.

There was a significant difference in the number of review matters closed with no review in 2020–21 compared to 2021–22. Twelve matters closed with no review in 2020-21 and 7 closed this year.

Closed with no review

Seven Ombudsman reviews were closed by the Ombudsman with no review taking place. Under s 82(5) of the FOI Act, the Ombudsman may decide not to review a decision if:

- the applicant has not given the Office enough information to review the decision

- there is no reasonable prospect that the original decision would be varied or set aside

- the agency or Minister makes a subsequent decision on the access application or otherwise resolves the application

- the Ombudsman is satisfied the review application is frivolous or vexatious or involves an abuse of process, or

- the Ombudsman is unable to contact the review applicant despite making reasonable efforts.

Under s 78 of the FOI Act, the Ombudsman may extend the time to decide an access application if an application for review of a deemed decision has been made.

Informal resolution

Where possible, before proceeding to a formal decision, the Ombudsman seeks to resolve reviews through informal resolution.

This involves clarifying and, in some cases, refining the scope of an application for review, and working with both parties to resolve the dispute. For example, if the applicant is focused on one particular document, the Ombudsman may ask the agency for its view on the release of that document, rather than review the whole matter. Informal resolution assists the Ombudsman to provide a satisfactory outcome for review applicants in a timely manner.

Where a matter is assessed as unlikely to result in a change of outcome, the Ombudsman uses case officer assessments to attempt to resolve the matter before progressing to a final decision. Parties are given information on the likely outcomes of the review and options for resolution. This approach reduces the overall timeframe for our reviews and saves the applicant additional legal fees where they have a legal representative.

Formal decision outcomes

From the commencement of the FOI Act on 1 January 2018 to 30 June 2022, a total of 85 Ombudsman review decisions have been published.[13] In 2021–22, 18 Ombudsman review decisions were published. These decisions provide agencies and applicants with guidance on the FOI Act, including the application of the public interest test.

Of the 18 Ombudsman reviews finalised with a formal decision in 2021–22, the Ombudsman:

- confirmed the agency’s decision in 5 Ombudsman reviews

- set the original decision aside and substituted a new decision in 6 Ombudsman reviews

- varied the original decision in 7 Ombudsman reviews.

Figure 12: Review applications finalised by outcome

Review timeframes

The FOI Act requires Ombudsman reviews be completed within 30 working days. Up to 30 additional working days are allowed to undertake informal resolution or if a matter is referred by the Ombudsman for mediation.

The Office also has internal service standards for Ombudsman review applications.[14] In 2021–22, we did not meet these internal service standards. Of the 30 Ombudsman reviews finalised:

- 23 per cent were finalised within 6 weeks (target 30 per cent)

- 47 per cent were finalised within 12 weeks (target 60 per cent)

- 70 per cent of reviews were finalised within 6 months (target 95 per cent).

While we aim to progress Ombudsman reviews as quickly as possible, timeframes can vary, particularly when a matter is complex or involves a large volume of documents for assessment. Timeframes can also extend if any of the parties seek additional time to make their submissions.

In the reporting period, the Office managed several Ombudsman reviews involving a large volume of documents, with novel and complex issues concerning multiple parties. This resulted in 30 per cent of Ombudsman reviews taking longer than 6 months to finalise. In 2022‑23, the Office will review its internal service standards and performance against those standards, with a view to reducing the time taken to complete Ombudsman reviews.

Appeals to ACAT

Under s 84 of the FOI Act, participants in an Ombudsman review may apply to ACAT for a review of the decision. Since the FOI Act commenced operation on 1 January 2018, no applications to ACAT for a review of an Ombudsman decision have been made.

Case study An applicant applied for Ombudsman review of a decision by Major Projects Canberra (MPC) to refuse access to some information related to the tender process for construction of new buildings on a school campus[15]. MPC refused access citing concerns about release adversely affecting the competing tenderer’s business affairs as it would reveal the tenderer’s sensitive commercial information. The review resulted in the decision being varied, with the Acting Senior Assistant Ombudsman (as delegate) deciding to release additional information, including the tender evaluation scores originally withheld by MPC. In making the decision, the Acting Senior Assistant Ombudsman placed greater weight on the pro-disclosure factors of ensuring effective oversight of the expenditure of public funds, revealing the reason for a government decision and any background or contextual information that informed the decision. |

Part 7: COMPLAINTS

The Ombudsman can investigate complaints about an agency or Minister’s functions under the FOI Act.

During this reporting period, the Office received 3 complaints about an agency’s functions under the FOI Act, a decrease from the 6 complaints received in 2020–21.

These complaints were about agencies’ actions performed under the FOI Act, including the time taken to process access applications and the decisions made by agencies.

The Office decided to investigate all 3 complaints. Two complaints were finalised with the agencies providing the complainants with the information requested, resolving the complainants’ concerns without the need for any further action. At the end of the reporting period, one complaint remained open.

Part 8: THE YEAR IN REVIEW

Oversight agency activities

In addition to delivering on the Ombudsman’s statutory functions under the FOI Act, the Office undertook educational and engagement activities during 2021–22.

Open Access monitoring

In 2021–22, the Office did not progress its Open Access monitoring strategy as planned during the reporting period. The Office did, however, continue to consult with stakeholders and provide assistance to agencies on areas to improve freedom of information practices.

The Office will progress its Open Access monitoring strategy in 2022–23, with a focus on agency education.

Engagement activities

Throughout 2021–22, the Office engaged with stakeholders in a variety of ways, considering the changing circumstances resulting from COVID-19, particularly in the first half of the reporting period. The Office continues to communicate informally with agencies, providing advice and clarification on FOI matters.

To mark International Access to Information Day on 28 September 2021, the Office released a joint statement with Information Commissioners and Ombudsmen across Australia.[16] The joint statement detailed the new ‘Open by Design Principles’. These principles encourage the proactive release of information by government agencies. This statement was accompanied by a consumer video to raise public awareness of information access rights.

The Office circulated a newsletter to ACT FOI practitioners in December 2021, providing updates on current events and trends and advising practitioners on dealing with access applications.

The Ombudsman attended 2 meetings of the Association of Information Access Commissioners, in September 2021 and April 2022.

The Office hosted a virtual FOI practitioners’ forum in February 2022, with more than 30 Information Officers from agencies attending. The forum was an opportunity to reconnect with ACT agencies and involved discussion on the feedback from a survey on community attitudes towards FOI and FOI matters that had recently received media attention.

Insights regarding agency decisions and behaviours

Following the fourth full year of the operation of the FOI Act, the Office can make some observations on trends in FOI decision-making and agency compliance with the FOI Act. These observations are based on the data provided by agencies, the Ombudsman’s review function, as well as feedback from engagement with agencies and the ACT community during the reporting period.

Decrease in applications for Ombudsman review

In 2021–22, agencies reported a substantial increase in the number of FOI access applications. The Office did not see a corresponding increase in Ombudsman review applications.

In 2021–22, agencies also reported a substantial increase in the number of decisions to publish Open Access information.

There may be a correlation between the increase in the amount of government information already available to the public through the Open Access information scheme, and the decrease in Ombudsman review applications.

The decrease in Ombudsman review applications may also indicate agencies are giving applicants clearer reasons for decision in matters where access is refused in whole or part.

While the Ombudsman received fewer Ombudsman review applications in 2021–22, the nature of the reviews undertaken has been increasingly complex.

FOI reviews about COVID-19 information

In 2021–22 the Office continued to receive requests for Ombudsman review related to COVID-19 information. This year, however, we have observed a shift from seeking access to information shared at National Cabinet, to seeking more specific information about how the ACT has managed COVID-19.

These Ombudsman reviews require careful balancing of the sensitivities involved in intergovernmental relations against the public interest in transparency around the ACT Government’s administration of public health during COVID-19.

Part 9: THE YEAR AHEAD

In 2022–23, the Ombudsman will continue to work with agencies and Ministers to encourage the proactive release of government information, and better practice in FOI decision‑making, in accordance with the objectives of the FOI Act.

One priority for the Office is to continue to develop and use education tools, including forums and newsletters, to complement the FOI guidelines in supporting FOI practitioners in the ACT. Having hosted a successful virtual practitioner forum in 2021–22, the Office is confident it can continue to work with agencies in person or remotely.

Another focus in 2022–23 will be to continue monitoring Open Access compliance in the ACT and supporting ongoing improvement through education.

Further, the Office will continue to:

- conduct reviews independently, efficiently and, wherever possible, informally resolve disputes

- promote better practice in FOI decision-making

- review and improve performance against the Office’s internal service standards for Ombudsman review

- raise awareness of the ACT community’s right to access government information and the Ombudsman’s oversight and review functions, and

- engage with interstate and Commonwealth counterparts to promote better practice and share information.

Part 10: GLOSSARY

Acronym | Agencies |

|---|---|

AAO | ACT Audit Office |

ACAT | ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal |

ACTO | ACT Ombudsman |

BCITF | Building and Construction Industry Training Fund |

CFC | Cultural Facilities Corporation |

CHS | Canberra Health Services |

CIT | Canberra Institute of Technology |

CMTEDD | Chief Minister, Treasury and Economic Development Directorate |

CRA | City Renewal Authority |

CSD | Community Services Directorate |

CSE | Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment |

DPP | ACT Director of Public Prosecutions |

EC | ACT Electoral Commission |

Education | ACT Education Directorate |

EPSDD | Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate |

Health | ACT Health Directorate |

HRC | ACT Human Rights Commission |

ICRC | Independent Competition and Regulatory Commission |

JACS | Justice and Community Safety Directorate |

LA | Legal Aid Commission |

LSA | Long Service Leave Authority |

MPC | Major Projects Canberra |

OLA | Office of the Legislative Assembly |

SLA | Suburban Land Agency |

TCCS | Transport Canberra and City Services Directorate |

TQI | Teacher Quality Institute |

UC | University of Canberra |

[1] This is subject to some exceptions, such as information under the Health Records (Privacy and Access) Act 1997 (see s 12 of the FOI Act).

[2] The FOI Act includes a comprehensive definition of agency (s 15).

[3] See: https://www.ombudsman.act.gov.au/publications/reports/annual-reports

[4] See page 3 of the Explanatory Statement to the Freedom of Information Bill 2016 at https://www.legislation.act.gov.au/View/es/db_53834/20160505-63422/PDF/db_53834.PDF

[5] See s 23 of the FOI Act for the list of categories of Open Access information.

[6] See: https://www.legislation.act.gov.au/ni/2020-368/

[7] See: https://www.ombudsman.act.gov.au/publications/foi-guidelines/open-access-information-01

[8] See: https://www.ombudsman.act.gov.au/ data/assets/pdf_file/0014/111182/ACTO-Open-Access- Strategy-updated-July-2020.pdf

[9] This dataset includes information provided by each directorate, not including smaller agencies within their portfolio. Separate data for each agency will be available in their respective annual reports.

[10] These being that the information is contrary to the public interest information and doing so would reasonably be expected to: endanger the life or physical safety of a person, be an unreasonable limitation on a person’s rights under the Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT), or significantly prejudice an ongoing criminal investigation. See s 35 of the FOI Act.

[11] See, for example, discussion by the NSW IPC in its Report on the Operation of the Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009 (NSW)| 2020-2021 at https://www.ipc.nsw.gov.au/information-access/gipa-compliance-reports

[12] See: https://www.legislation.act.gov.au/di/2018-197/

[13] See: https://www.ombudsman.act.gov.au/improving-the-act/freedom-of-information/foi-review-decisions

[14] See: https://www.ombudsman.act.gov.au/improving-the-act/freedom-of-information/foi-complaints-and-reviews

[15] Manteena Commercial Pty Ltd and Major Projects Canberra [2021] ACTOFOI 9 (8 September 2021).

[16] ACT Ombudsman, Information Access Commissioners and Ombudsmen make recommendations to support Open by Design Principles webpage, viewed 14 June 2022, https://www.ombudsman.act.gov.au/home/home-news/Information-Access-Commissioners-and-Ombudsmen-make-recommendations-to-support-Open-by-Design-Principles.