Analysis of agency performance

ANALYSIS OF AGENCY PERFORMANCE

Since 1 July 2011, ACT government administration has been organised within nine directorates. The current structure of the ACT Government is set out in Notifiable Instrument NI2011-712, Administrative Arrangements 2011 (No 3).

ACT GOVERNMENT DIRECTORATES—

APPROACHES AND COMPLAINTS

Chief Minister and Cabinet Directorate

Overview

The directorate is responsible for:

- directing and coordinating policy and strategy across the ACT Public Service, managing the ACT’s inter-governmental relationships, and supporting the Chief Minister’s role on the Council of Australian Governments

- strategic planning and direction on public sector standards, including service-wide employment, workforce culture and capability, industrial relations, learning and development, implementing machinery of government changes, and promoting ethics and accountability

- community engagement, whole-of-government communications, public affairs advice and planning, and delivery of the Centenary of Canberra

- supporting the Head of Service and the Strategic Board and its sub-committees.

The Chief Minister and Cabinet Directorate has limited service delivery obligations to the general public. Therefore, it is not surprising that very few complaints are made to the Ombudsman about the administrative functions of this directorate.

Complaints and investigations

In 2011–12, the office received three approaches and finalised two about activities within the portfolio of the Chief Minister and Cabinet Directorate. This is less than 1% of all complaints and approaches received by the ACT Ombudsman in 2011–12.

Other significant engagement

In July 2011, the Ombudsman made a submission to the inquiry by the Legislative Assembly Standing Committee on Administration and Procedure into the feasibility of establishing the position of Officer of the Parliament.9

On 23 November 2011, the reporting functions of the ACT Ombudsman’s office moved from the Justice and Community Safety Directorate to the Chief Minister and Cabinet Directorate, under the Administrative Arrangements 2011 (No 3).

In May 2012, the Acting Ombudsman and the Director-General of the Chief Minister’s Directorate met to discuss how the office could better assist the directorate to improve complaint management across the ACT Public Service. These meetings will occur every six months. The ACT Ombudsman and the ACT Government will implement a new service delivery agreement in late 2012.

Table 4: Approaches and complaints received about the Chief Minister and Cabinet Directorate 2011–12

| Chief Minister and Cabinet | Received | Finalised | ||

| Total | Not Investigated | Investigated | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chief Minister’s Department | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| ACT Legislative Assembly | 1 | |||

| 3 | 2 | |||

HEALTH DIRECTORATE

Overview

The Health Directorate sets health policy, plans the delivery of health services, and seeks to ensure that these services meet community needs. The Health Directorate also funds a range of non-government organisations to provide vital healthcare services to the people of the ACT and surrounding region.

The provision of health services, disability services and services for young people or older people are matters specifically excluded from the ACT Ombudsman’s jurisdiction under s 5(2)(n) of the ACT Ombudsman Act. While the office receives complaints and enquiries about these matters, they are generally referred to the ACT Human Rights Commission without further investigation unless special circumstances justify another course of action.

Complaints and investigations

In 2011–12, the office received 15 approaches and complaints (2% of the total approaches and complaints received) about activities within the Health Directorate: three were investigated. The issues noted in these approaches included actions taken by health inspectors, requests under Freedom of Information (FOI) and delays in processing payments. The majority of approaches concerned the provisionof health services and, because the Ombudsman has no jurisdiction over these complaints, they were referred to the ACT Human Rights Commission.

Other significant engagement

In May 2012, the responsible Senior Assistant Ombudsman met with the Director-General of Health to discuss the integrity of emergency department data.

Table 5: Approaches and complaints received about the Health Directorate 2011–12

| Health | Received | Finalised | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Not Investigated | Investigated | Total | |

| ACT Health | 15 | 14 | 3 | 17 |

| 15 | 17 | |||

TERRITORY AND MUNICIPAL SERVICES DIRECTORATE

Overview

The Territory and Municipal Services Directorate (TAMS) delivers a wide range of services to the ACT community, such as recycling and rubbish collection, public libraries and municipal infrastructure (streetlights and public barbeques, for example).

The directorate is responsible for managing roads, footpaths and cycle paths and operating the public transport system (ACTION). The directorate also looks after the ACT’s parks and reserves, such as Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve, Namadgi National Park and the reserves that make up Canberra Nature Park.

Canberra Connect, which is the main contact point for ACT government information, services and payments on behalf of other ACT Government agencies, is also part of the directorate.

The directorate is responsible for several of the ACT Government’s commercial operations, including ACT NOWaste, Capital Linen Service, Yarralumla Nursery, ACT Public Cemeteries Authority (which includes Woden, Gungahlin and Hall cemeteries) and ACT Property Group.

Complaints and investigations

Ten per cent of the approaches and complaints received in 2011–12 were about TAMS service delivery functions.

In 2011–12 we received 73 approaches and complaints about activities of the Territory and Municipal Services Directorate, of which we investigated 18. The issues in these approaches and complaints included:

- transfer of credit to MyWay cards

- maintenance of stormwater drains

- maintenance of footpaths

- damage to property following works on a nature strip

- payment of dog registration fees

- approvals for driveways across nature strips

- delays in responding to correspondence and phone calls

- failure to investigate the alleged actions of a bus driver

- lack of disabled parking spaces at a shopping centre.

In April 2011 ACTION introduced the MyWay electronic card system for bus passengers. The office received 12 complaints about the introduction, most stemming from ACTION’s decision not to transfer funds from pre-purchased park-and-ride tickets to MyWay cards after 11 April 2011. The Ombudsman investigation into this issue found that the policy for transferring credit from pre-purchased tickets had not been made clear to ACTION customers.

As shown in Table 7, the remedy provided to the complainant in 79% of the investigated complaints about TAMS was an explanation of the directorate’s processes or decision in way that the complainant could understand. This indicates that considerably more work could be done in this area. Case study 1 illustrates this point.

Table 6: Approaches and complaints received about TAMS 2011–12

| TERRITORY AND MUNICIPAL SERVICES | RECEIVED | FINALISED | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | NOT INVESTIGATED | INVESTIGATED | TOTAL | |

| Territory and Municipal Services Directorate | 57 | 46 | 10 | 56 |

| ACTION | 16 | 10 | 8 | 18 |

| 73 | 74 | |||

Table 7: Remedies for investigated complaints about TAMS 2011–12

| TYPE OF REMEDY | PER CENT |

|---|---|

| Action expedited | |

| Apology | 5 |

| Decision changed or reconsidered | 11 |

| Disciplinary action | |

| Better explanation provided | 79 |

| Financial remedy | |

| Other non-financial remedy | |

| Remedy provided without Ombudsman intervention | 5 |

Case Study 1

Basic vet checks for impounded dogs reasonable

An Ombudsman investigation recommended that TAMS provide clear information about the scope of veterinarian checks to people purchasing animals from the Domestic Animal Services Shelter.

Ms A complained to the Ombudsman after she was advised by a private veterinarian that her dog—purchased from the Domestic Animal Services Shelter—required significant and expensive remedial surgery. Before purchasing the dog, Ms A was told by the shelter that the dog would be given a check by the shelter’s veterinarian. Ms A said that if she had known about the dog’s pre-existing condition, she may not have bought it. She also thought that the ACT Government should pay for the dog’s surgery.

When the shelter became aware of Ms A’s complaint, she was advised that she could return the dog and receive either a refund or another animal. This office considered the shelter’s response administratively reasonable.

The investigation found that the veterinarian check for impounded dogs was basic, as might be expected given the shelter’s resources and functions as a holding pound. The purpose of the shelter is to find new homes for animals that would otherwise be destroyed. It therefore functions differently from a retail pet shop. When a person adopts an animal from the shelter, a nominal fee is charged as a contribution towards vaccinating, micro-chipping and registering the animal. However, it appeared that the limits of the vet-check were not clearly explained to prospective owners.

The Ombudsman recommended that the shelter consider better highlighting the limitations of the vet-check on its website, shopfront and in supporting documents to ensure prospective pet purchasers are properly informed.

Complainants often advise the ACT Ombudsman’s office that Canberra Connect officers have provided inaccurate information to them or failed to respond to their enquiries. However, our investigations have tended to show that the fault lies with the directorate or business area Canberra Connect has referred the complaint to rather than with Canberra Connect itself. In these circumstances Canberra Connect becomes a one-way communication channel only, and Canberra Connect cannot take responsibility for ensuring that the business area referred to will keep the complainant informed of any progress being made to resolve the complaint. Furthermore, complainants are often unaware that their complaint has been transferred to an external directorate or business area and that they are no longer dealing with Canberra Connect officers. Case study 2 demonstrates how this can create frustration for the complainant.

Case Study 2

Canberra Connect can’t track the actions of external business areas

In July 2011, Mr B lodged an online complaint with TAMS via Canberra Connect’s Fix My Street online reporting facility. The complaint concerned an unsafe footpath. TAMS advised Mr B that the information had been referred to ActewAGL.

A week later, Mr B raised the matter again via Canberra Connect because the footpath had not been repaired. While TAMS had been advised by ActewAGL on 8 August 2011 that the repairs should have been completed, TAMS did not provide this information to Mr B.

In September 2011, Mr B contacted Canberra Connect twice more because the repairs carried out on the footpath had deteriorated and it was again unsafe. In December 2011, Mr B received an email advising that the repairs had been inspected and were considered reasonable.

Mr B advised Canberra Connect that he believed the wrong location had been inspected. A further inspection was carried out and Mr B was advised that additional repairs would be arranged. In January 2012, Mr B was advised that the repairs had been completed.

While it appears that TAMS and ActewAGL were acting on Mr B’s information, Mr B was not kept informed and became frustrated by an apparent lack of action. While Mr B was making his contacts consistently via Canberra Connect, the matter needed to be addressed by two other agencies: TAMS and ActewAGL. Further, TAMS did not monitor the situation. Without Mr B’s continued involvement, TAMS would not have been aware that safety issues persisted.

On the Ombudsman’s recommendation, the directorate apologised to Mr B in writing for its poor handling of the matter and the delay he experienced.

Canberra Connect officers provide information to complainants from scripts that are based on information provided by relevant directorates or business areas. However, Ombudsman investigations have identified that these scripts are not always current. To ensure that information provided to the community is up to date, it is essential that all directorates update the information held by Canberra Connect to reflect changes in policies, procedures and legislation in a timely manner.

Complaints also arise because a process ‘falls through the cracks’ and a complaint is not appropriately followed up by the responsible area of the ACT Government. Case study 3 illustrates how the failure to follow-up on requests for assistance led to a four month delay and a dissatisfied member of the community.

Other significant engagement

In July 2011, Ombudsman staff attended the Belconnen bus interchange for a demonstration on how the MyWay system operates.

In February 2012, Ombudsman staff met with the Deputy Director-General of the directorate. One outcome of this meeting was an agreement between the parties to meet quarterly to facilitate more direct and timely communication regarding complex complaints.

Case Study 3

Dog registered at long last

Ms C received a written apology for the inconvenience she experienced as a result of unreasonable delay.

In August 2011, Ms C registered her dog through the ACT Government website and made the payment online. The payment was deducted from her credit card on 13 August 2011. In December 2011, Ms C approached the ACT Ombudsman because she had not received the dog tag or a receipt.

On investigation, the directorate confirmed that after the credit card payment was processed, the application ‘stalled’. The directorate also confirmed that when Ms C contacted Domestic Animal Services (DAS) in August and October 2011, no action was taken. The start of this office’s investigation on 14 December 2011 prompted action and the dog tag and receipt were posted to Ms C on 19 December 2011.

The Ombudsman investigation also prompted DAS to review and update its procedures for dealing with emails and handling registration enquiries.

TREASURY DIRECTORATE

Overview

The Treasury Directorate provides strategic financial and economic advice and services to the ACT Government with the aim of improving the ACT’s financial position and economic management.

Functions and business units within the directorate include:

- ACT Public Sector Shared Services

- budget policy advice, process and financial reporting

- competition policy and regulatory reform

- fiscal and economic policy (including macroeconomic policy and forecasting, in conjunction with Chief Minister and Cabinet)

- Government Business Enterprises ownership policy

- insurance public funds management

- procurement policy

- taxation

- revenue policy and collection.

Complaints and investigations

The office received 19 approaches and complaints (3% of the total approaches and complaints received) about activities within the Treasury Directorate in 2011–12. One complaint was investigated.

Complaints about Treasury’s administrative functions generally relate to one of three issues: revenue collection, such as rates or land tax; requests for waivers for accrued debts; or instalment plans for payment. The office also received approaches from people seeking legal advice on their liability

for accrued debts. The office cannot provide legal advice or advocacy for complainants, so these people were advised to seek independent legal advice. No investigation was undertaken.

The one complaint investigated in 2011–12 involved the receipt by Treasury of a request to waive a debt accrued by a public housing client. Housing ACT had forwarded the request to Treasury, but the request had not been signed. Because the request was not signed, Treasury took no action on it. Consequently neither agency pursued the matter and the request remained un-actioned for more than 12 months, when the complaint came to the attention of the Ombudsman's office.

Table 8: Approaches and complaints received about the Treasury 2011–12

| TREASURY | RECEIVED | FINALISED | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | NOT INVESTIGATED | INVESTIGATED | TOTAL | |

| Treasury Directorate | 19 | 18 | 0 | 18 |

| 19 | 18 | |||

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DIRECTORATE

Overview

The Economic Development Directorate aligns and coordinates land release and development, property management and major projects within the ACT.

The directorate is responsible for:

- business support programs

- Coordinator-General Events (including Territory Venues, Exhibition Park in Canberra)

- Government property strategy

- land development

- land release policy (including the Land Release Program)

- major land and property project facilitation

- skills and economic development

- sport and recreation

- tourism

- gaming and racing.

Complaints and investigations

In 2011–12, the office received 45 complaints about activities within the Economic Development Directorate, the majority concerning the collapse of online betting company Sports Alive. Complainants urged the Ombudsman’s office to investigate the actions of the ACT Gambling and Racing Commission following allegations that Sports Alive had failed to maintain segregated accounts for clients’ monies—a requirement for holding a betting license in the ACT. This matter has become intrinsically connected to ongoing legal actions concerning Sports Alive’s insolvency. At the end of the reporting period, the office was still considering a range of material associated with the collapse of Sports Alive.

Complaints are occasionally received about land releases and sales. Generally, these concern prevailing Government policies that govern or restrict the availability of land for development, and therefore are not matters that the Ombudsman can investigate. Where it is decided that a complaint is a matter of government policy, and not administrative action, the complainant is referred to the minister or to members of the Legislative Assembly.

Table 9: Approaches and complaints received about the Economic Development Directorate 2011–12

| ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT | RECEIVED | FINALISED | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | NOT INVESTIGATED | INVESTIGATED | TOTAL | |

| ACT Gambling and Racing Commission | 42 | 22 | 4 | 26 |

| ACT TABa | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Department of Land and Property Services | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 45 | 29 | |||

JUSTICE AND COMMUNITY SAFETY DIRECTORATE

Overview

The Justice and Community Safety Directorate and associated agencies provide services to the Canberra community in the areas of:

- justice

- emergency preparedness and response

- regulation of many consumer and business activities

- protection of rights.

The directorate’s responsibilities include:

- administration of justice

- electoral services

- fair trading and registration

- inspection and regulatory services (including transport regulation and licensing)

- human rights

- legal policy and services

- road safety, driver and vehicle licensing policy

- emergency services and policing

- corrective services.

Complaints and investigations

In 2011–12, 24% of approaches and complaints received by the office were about matters within the Justice and Community Safety Directorate (JACS).

Complainants sometimes seek legal advice or review of a decision made by a tribunal or court, but such matters are outside the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction. Accordingly, these complainants are usually referred to an appropriate body and the matter closed without investigation. Complaints about the deliberative actions of judicial officers are likewise outside the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction, although complaints about

administrative actions within the ACT’s courts and tribunals may be investigated.

In May 2012, the Ombudsman published a report under s 18 of the ACT Ombudsman Act following investigations of two complaints about the handling of applications for financial assistance under the Victims of Crime (Financial Assistance) Act.10 The investigations identified that the administrative arrangements in place for progressing and finalising applications were inadequate. The Ombudsman recommended a review of the arrangements with a view to putting a more structured process in place. The Attorney-General responded positively, directing his officials to provide him with detailed advice on alternative models for administering the scheme, having regard to the Ombudsman’s recommendation. In 2012–13, the office will follow-up with the JACS directorate on its progress.

In 2011–12 we received 181 approaches and complaints about activities within the JACS, of which we investigated 53. As identified in Table 10, 73 of the 181 approaches and complaints were about ACT Corrective Services. Complaints about administrative actions by the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal (ACAT), ACT Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), Public Trustee for the ACT and ACT Office of Regulatory Services were also investigated.

Table 10: Approaches and complaints received about the JACS Directorate 2011–12

| JUSTICE AND COMMUNITY SAFETY | RECEIVED | FINALISED | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | NOT INVESTIGATED | INVESTIGATED | TOTAL | |

| Justice and Community Safety Directorate | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| ACT Corrective Services | 73 | 47 | 34 | 81 |

| ACT Office of Regulatory Services | 39 | 23 | 9 | 32 |

| Public Trustee for the ACT | 17 | 12 | 4 | 16 |

| Legal Aid Commission for the ACT | 14 | 13 | 13 | |

| ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal | 12 | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| ACT Director of Prosecutions | 9 | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| ACT Human Rights Commission | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| ACT Government Solicitor | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Supreme Court of the ACT | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Office of the Public Advocate of the ACT | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| ACT Magistrates Court | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 181 | 181 | |||

The issues in the complaints investigated included:

- ƒuse of force incidents by correctional officers

- lost and damaged detainee property in the AMC

- restrictions imposed on visitors to the AMC

- management of detainee requests and grievances

- items seized or confiscated from detainees or visitors to the AMC

- detainee classification and placement within the AMC

- safety of protected detainees within the AMC

- detainee disciplinary procedures and penalties imposed for breaches of discipline

- procedural/administrative information available to the relative of an accused person

- timeliness of proceedings in the ACAT

- regulation of asbestos removal works in domestic residences

- driver licence disqualifications and cancellations

- parking infringement notices, disputes and late fees

- delays in registration renewals.

Case Study 4

Review of detainee property management at the AMC

Property management practices at the AMC are to be reviewed following an investigation by the Ombudsman into a complaint about property being signed out to the wrong person.

Management of detainees’ property at the AMC has been a source of numerous complaints to the ACT Ombudsman’s office. In one case in 2011–12, the property belonging to one detainee was signed out to another person leaving detention who happened to have a similar name. The Ombudsman recommended that if the property could not be recovered from the person to whom it had been given, then ACT Corrective Services should consider compensating the owner of the property to an agreed value.

In another case, a detainee complained that his suit, which was held in AMC storage, had been worn by other detainees when attending court. The office was not able to verify whether this had in fact occurred, but noted that the property management protocols and the records held at the AMC could not be relied upon to ensure that this had not happened, or could not happen.

Recently, the Superintendent advised that a review of property management at the AMC will be undertaken in the near future. It is expected that the office will be invited to provide input to that review.

Table 11: Remedies for investigated complaints about the JACS Directorate 2011–12

| TYPE OF REMEDY | PER CENT |

| Action expedited | 2 |

| Apology | 2 |

| Decision changed or reconsidered | 4 |

| Disciplinary action | 4 |

| Better explanation provided | 64 |

| Financial remedy | 7 |

| Other non-financial remedy | 4 |

| Remedy provided without Ombudsman intervention | 13 |

As shown in Table 11, a better explanation is the most frequent remedy provided to people who make complaints about processes within the JACS directorate. This is not surprising, given the portfolio of the directorate. JACS clients frequently find themselves in unfamiliar circumstances, having to deal with legal issues they have never previously confronted. There is significant potential for confusion about unfamiliar processes and legal consequences following a client’s action or inaction.

The following two case studies demonstrate the difficulties people sometimes have when dealing with complex legal circumstances that involve JACS agencies. In both these cases, remedies involved providing to the complainants an explanation for what had happened and why.

Case Study 5

Complex processes given meaning

Ms D was given a clearer and simpler explanation of complex legal processes as a result of an Ombudsman investigation.

Ms D’s husband was arrested and charged with serious offences. The DPP did not oppose bail. The court granted Ms D’s husband bail with conditions that allowed him to reside with her and their family.

Ms D complained to the Ombudsman’s office because she felt that the DPP should have advised her of her legal right not to sign as surety for her husband. Later, when her husband was arrested for other offences involving a family member, Ms D felt that a copy of the new bail conditions should have been provided to her. Ms D felt aggrieved because she thought the DPP should have treated her more sympathetically, perhaps even as a victim of the crime.

In investigating these kinds of complaints, it is important to manage the expectations of the complainant. There is a need to clarify that the Ombudsman’s powers are limited to investigating administrative processes but we cannot comment on the deliberative functions of delegated officers. The office investigated the administrative issues in this complaint, including the DPP’s role in providing information to Ms D about her husband’s bail on both occasions; the DPP’s role in relation to victims of crime; and the DPP’s ongoing engagement with Ms D in relation to the proceedings of the court case.

While the office was unable to comment on the deliberative decision made by the DPP in respect to bail, Ms D was provided with a better explanation of the other processes, including what had occurred in court. The office concluded that the DPP had followed its procedures appropriately.

Case Study 6

Public Trustee acted appropriately

Ms E complained on behalf of her mother that the Public Trustee had failed in its duty of care when it failed to pay her stepfather’s portion of the bond for an aged care facility. Ms E had enduring power of attorney for her mother; the elderly couple kept their estates separate. Ms E advised that the aged care facility income-tested her mother and increased her bill in light of her stepfather’s bond not being paid. Consequently her mother’s fees were increased by more than $500.

By way of remedy, Ms E wanted the Public Trustee, who had enduring power of attorney for her stepfather, to pay his bond so that her mother’s income-tested fee could be reduced.

The Ombudsman investigation found that the Public Trustee had been appointed as the enduring power of attorney for Ms E’s stepfather. As such, the Public Trustee bore no duty of care towards Ms E’s mother and had acted appropriately in its dealings with her stepfather.

In fact, the Public Trustee had informed Ms E of the reasons it had taken the action it did in relation to her stepfather’s situation. Further, the Public Trustee, in its attempt to resolve the matter, identified an oversight by the aged care facility that affected the income test assessment, which was then communicated to Ms E by this office.

The circumstances of Ms E’s mother and stepfather were legally complex, but our investigation allowed us to provide a clearer explanation of the Public Trustee’s role in the case.

Other significant engagement

In the second part of 2011–12, the Acting Executive Director, Governance within the JACS directorate and the Director of the ACT team within the Ombudsman’s office implemented quarterly liaison meetings. The responsible Senior Assistant Ombudsman met with the JACS Executive in late June 2012. It is hoped that meetings with the Executive will take place every six months.

The Senior Assistant Ombudsman and the Executive Director of the AMC also met regularly throughout the year.

Staff of the ACT Ombudsman’s office participate in the regular Oversight Agencies Working Group meetings held at the AMC, the ACT’s full-time correctional centre. The purpose of these meetings is to discuss the prevailing circumstances in the AMC, including health services, accommodation issues, management of complaints and grievances, program availability and participation, and access to welfare and assistance services for detainees.

ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT DIRECTORATE

Overview

The Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate incorporates sections of what was formerly the Department of Environment, Climate Change, Energy and Water, ACT Planning and Land Authority (ACTPLA), transport planning, heritage, Government Architect, and Conservator of Flora and Fauna.

The directorate’s responsibilities cover:

- climate change policy

- electricity and natural gas, water and sewerage industry technical regulation

- energy policy and energy efficiency programs

- environmental sustainability policy

- environment protection

- Government Architect

- heritage

- occupational licensing

- planning, development and building control

- strategic land use and transport

- planning

- support to the Conservator of Flora and Fauna

- survey and leasing

- water policy and water efficiency programs.

Section 5(2)(h) of the ACT Ombudsman Act excludes action taken in managing the environment (other than stormwater and street lighting) from the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction. Complaints about these matters are referred to the Commissioner for the Environment. Complaints about water supply (ACTEW), such as disputes over billing, are handled by ACAT. Most approaches to the Ombudsman’s office about these matters are referred to ACAT without investigation.

Complaints and investigations

In 2011–12 the office received 80 approaches and complaints (10% of the total complaints and approaches) about activities within the Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate, of which 15 were investigated. Thirteen of these concerned the actions of ACTPLA. The issues in these complaints included:

- conduct of controlled activities on neighbouring properties

- Development Application approvals, submissions and delays

- planning approvals without public notification

- decision notices not written in plain language

- claims against builders and certifiers

- delays in certifying solar panel installations.

All investigated complaints were finalised by providing a better explanation to the complainant. Case study 7 demonstrates the need for simple and clear language in explaining complex planning regulations and decisions.

Case Study 7

Plain English required to explain technical notices

Ms F was uncertain whether or not she could seek a review of ACTPLA’s decision to unconditionally approve her neighbour’s development application at the ACAT.

Ms F had received a copy of the Notice of Decision (from ACTPLA) because she had made a representation in response to the development application. The notice included generic administrative information about ACAT review rights, but did not link this information to the specific circumstances of Ms F’s case. Standard template paragraphs were used in the notice, making it difficult to determine whether or not the development application was exempt from ACAT review.

When Ms F contacted ACTPLA officers to seek clarification, she was advised, verbally and in emails, that in the officer’s view the development was of a type that was exempt from third-party review at ACAT. Ms F remained uncertain and asked the Ombudsman’s office for assistance in clarifying the matter.

In response to the office’s enquiries, ACTPLA advised:

‘The proposal is for the building of a class 10 building (non-habitable), and is therefore identified for limited public notification under Item 6 listed in Schedule 2 of the Planning and Development Regulation 2008. In terms of Item 1 listed in Schedule 3 of the Planning and Development Regulation 2008, a development identified for limited public notification is exempt from third-party review in the ACAT. …On this basis, it is the Authority’s view that the approval is exempt from third-party review in the ACAT.

It is however, important to note that the jurisdiction to allow an application for review ultimately resides with the Tribunal, and it is not a matter for the Authority to decide. The Authority therefore refrains from providing specific advice in this regard in the Notice of Decision.’

This advice is consistent with the information provided to Ms F in telephone and email contacts, but it was not clearly stated in the Notice of Decision. The Ombudsman recommended that ACTPLA consider reviewing its Notice of Decision to make it easier for people unfamiliar with the building regulations to understand.

Another important aspect of communicating with complainants is keeping them informed. As demonstrated by Case study 8, keeping complainants informed of developments can alleviate dissatisfaction and prevent further problems.

Case Study 8

Communicate with complainants

On the Ombudsman’s recommendation, ACTPLA formally responded to Ms G in February 2012, more than six months after she lodged a complaint with the agency.

When Ms G moved into her new house she was concerned about the condition of several items, such as the kitchen cupboards, kitchen taps and a water saving pump. Ms G was dissatisfied with the builder’s response to her concerns and in August 2011 complained to ACTPLA.

Ms G received a prompt response from ACTPLA advising that her complaint was being considered, but when she had not received a substantive response by November 2011, Ms G complained to the Ombudsman’s office.

The Ombudsman investigation identified that ACTPLA officers had considered Ms G’s concerns but were satisfied with the builder’s response. Some of Ms G’s concerns related to the ‘fit and finish’ of the property, which were not in ACTPLA’s jurisdiction and should have been raised with the ACT Office of Fair Trading. Unfortunately, this information was not provided to Ms G.

COMMUNITY SERVICES DIRECTORATE

Overview

The ACT Government Community Services Directorate is responsible for a wide range of human services functions in the ACT, including the areas of:

- multicultural affairs

- community services

- older people

- women

- public and community housing services and policy

- children, youth and family support services and policy

- disability policy and services

- therapy services

- Child and Family Centres

- the ACT Government Concessions Program

- homelessness

- community engagement

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs

- community disaster recovery.

Many of the directorate’s portfolio responsibilities fall outside the ACT Ombudsman’s jurisdiction to investigate by virtue of s 5(2)(n) of the ACT Ombudsman Act. Complaints about matters outside the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction are referred to an appropriate body without investigation. The majority of Community Services Directorate complaints are referred to the ACT Human Rights Commission, either by referring the complainant to that body or by formally referring the complaint details to the Commission under s 6A or 6B of the ACT Ombudsman Act.

Complaints and investigations

In 2011–12, the office received 170 approaches and complaints (22% of all approaches and complaints) about activities within the Community Services Directorate. Twenty-one of these were outside the ACT Ombudsman’s jurisdiction and the complainants were referred to another appropriate oversight body. There were 151 complaints concerning housing, of which 41 were investigated by this office.

The issues in these complaints included:

- action taken to address antisocial behaviour by tenants

- action taken to recover debts, accrue debts, waive debts or write off debts

- assessments of applications for housing or transfer

- calculation of rental rebates

- engagement between tenants and housing managers

- lost amenities while maintenance works carried out

- management of complaints

- settlement of compensation claims

- time taken to allocate appropriate housing to ’high needs’ and ’priority’ applicants

- timeliness or quality of maintenance actions.

A frequent topic of complaint about Housing ACT is delay in maintenance services, as illustrated in Case study 9.

Table 12: Approaches and complaints received about the Community Services Directorate 2011–12

| COMMUNITY SERVICES | RECEIVED | FINALISED | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | NOT INVESTIGATED | INVESTIGATED | TOTAL | |

| Office for Children, Youth and Family Support | 19 | 21 | 1 | 22 |

| Housing ACT | 151 | 96 | 41 | 137 |

| 170 | 159 | |||

Table 13: Remedies for investigated complaints about the Community Services Directorate 2011–12

| TYPE OF REMEDY | PER CENT |

| Action expedited | 18 |

| Apology | 12 |

| Decision changed or reconsidered | 5 |

| Disciplinary action | 3 |

| Better explanation provided | 50 |

| Financial remedy | |

| Other non-financial remedy | 5 |

| Remedy provided without Ombudsman intervention | 7 |

Case Study 9

Public housing repairs and maintenance problems solved

Housing ACT apologised to one of its tenants and undertook to work with her to make necessary repairs and review maintenance charges following a complaint investigation by the Ombudsman.

Ms H complained about ongoing problems with her Housing ACT property. These included blockages with plumbing and insecure external windows. Ms H said that the windows were insecure because the house had subsided over time. She also said that, as a consequence of the insecure windows, she had been the victim of burglary. Ms H complained to the Ombudsman’s office after having repeatedly reported the matter to the maintenance contractor without the problems being rectified.

The Ombudsman investigated the complaint and raised concerns with Housing ACT that both issues (with the property) pre-dated Ms H’s tenancy.

Housing ACT issued the maintenance contractor with a non-compliance notice.

Complaints about antisocial neighbours

The ACT Ombudsman’s office receives complaints from neighbours of public housing tenants who say that they have been disrupted by antisocial behaviour. Complainants report that despite having complained to Housing ACT and to the police, no action has been taken to curb the behaviour or to evict nuisance tenants. Sometimes the complainant will also be a public housing tenant or resident. In these cases, both neighbours will usually have the same housing manager; the complainant will usually expect the housing manager to take some action against the nuisance neighbour.

Antisocial behaviour may include excessive noise, vulgar language, verbal abuse, threats to property or person, actual damage to property and, in some cases, altercations and assaults.

The Ombudsman’s investigations of these complaints have shown that these matters can become intractable and difficult to resolve within timeframes considered reasonable for the complainant. Public housing tenants have the same rights in law as private rental tenants. Housing ACT cannot summarily evict tenants and has no lawful right to intervene in the lives of people who happen to have Housing ACT as a landlord. People who live in, or adjacent to, public housing may have an expectation that antisocial or nuisance tenants who are moved into their neighbourhood by Housing ACT can be just as easily moved out. This is not the case.

Once a lease has been signed, a public housing tenant can only be evicted from the premises if it is proven that they have breached the conditions of the lease. Like any other landlord, Housing ACT must obtain orders from the ACAT or from a court to evict a tenant. A court or tribunal will only issue such orders if it is satisfied that the breach of the tenancy conditions is proven, the tenant has been afforded procedural fairness including rights to appeal and to be heard, eviction is warranted in the case, and no other course of action is reasonably open in the circumstances. Establishing a case and obtaining orders can be a protracted process.

All public housing tenants are required to refrain from disrupting their neighbourhood. Doing so can constitute a breach of the tenancy agreement.

Nonetheless, proving that such a breach has occurred requires documented evidence. This can be in the form of Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) noise measurements, police records, statutory declarations from witnesses and the like. A one-off or single instance will not warrant eviction. Generally, a tenant will only be evicted if there is a pattern of ongoing antisocial behaviour that is reasonably serious, and the tenant has disregarded reasonable requests to curb or moderate the behaviour. Again, it is a protracted administrative process to obtain this evidence and it usually falls to the complainant to document instances of antisocial behaviour affecting them. Complainants consider this frustrating and unfair; they believe that they are doing the job that Housing ACT or the police should be doing to establish a case against the nuisance neighbour.

When Housing ACT receives a complaint about alleged antisocial behaviour, officers will investigate the circumstances and try to establish the veracity of the complaint. Sometimes the tenant will admit to the behaviour or an incident. Where the complaint involves behaviour that has been or may have been reported to police, Housing ACT officers will request police attendance records under a Memorandum of Understanding between Housing ACT and the AFP. If the EPA has made noise measurements that support a complaint of excessive noise, these will be provided to Housing ACT.

Following a complaint about antisocial behaviour, Housing ACT will inform the tenant that there has been a complaint but not identify the complainant. The tenant will be reminded of their obligations under the tenancy agreement not to disrupt the quiet enjoyment of other people’s residences. If the complaint is verified through documented evidence, Housing ACT will issue the tenant with a Notice to Remedy. This essentially warns the tenant that if the behaviour continues then Housing ACT may start legal action that may proceed to an eviction.

Any action that Housing ACT takes remains private and confidential. The complainant generally has no lawful right to know what, if anything, Housing ACT has done or said to the tenant about whom they have complained. This again creates frustration for the complainant and reinforces their view that Housing ACT is ‘doing nothing’. The Ombudsman’s office is also bound by privacy and confidentiality not to disclose the details of investigations to complainants. If an investigation finds that Housing ACT has done as much as is reasonable in the circumstances, the complainant is advised of the outcome, but no details are disclosed. If an investigation finds that Housing ACT could take further action, the Ombudsman may recommend to Housing ACT that the action be considered. Again, the complainant cannot be informed of any Ombudsman recommendations other than those that concern Housing’s ACT’s engagement with the complainant.

Some complainants have reported that they or their family members have become so traumatised by their experiences that they now require medical or psychological intervention to cope. Where the complainants are public housing tenants, they may feel particularly aggrieved that Housing ACT appears to be unable or unwilling to take effective action to remedy the situation. While some affected neighbours will take up the option to apply to be transferred to another property, even for those on the ’high needs’ or ’priority’ transfer lists, this may take months to arrange.

Recently, the Minister announced policy changes that will allow provisional tenancies to be offered to some tenants. It is intended that for these tenants the administrative procedures for responding to complaints of antisocial behaviour will be streamlined. Also, Housing ACT has set up a new business unit to engage more actively with tenants who have attracted complaints of antisocial behaviour. The ACT Ombudsman’s office will monitor the effectiveness of these initiatives, and the support and assistance extended to complainants while they wait for a matter to be resolved.

Other significant engagement

As public housing matters make up a substantial proportion of complaints received and investigated by the office, liaison meetings with Housing ACT officers are held regularly to discuss strategic initiatives, policy and legislative matters, and complaint trends affecting the agency and its clients.

There were five liaison meetings in 2011–12, where topics included:

- response and follow-up to the Ombudsman’s 2011 s 18 report, Assessment of a Priority Housing

Application (01/2011) - Housing ACT’s new Gateway Services shopfront

- managing issues of antisocial behaviour committed by, or affecting, Housing ACT tenants

- calculation of rental rebates

- effects of stimulus spending on public housing waiting lists

- applicants’ expectations from published average waiting times

- property maintenance, including asbestos removal

- the Housing for Young People program

- Housing ACT’s responsibility for property maintenance management.

In 2011, the ACT Legislative Assembly Standing Committee on Health, Community and Social Services started an inquiry into the provision of public housing in the ACT. The Ombudsman’s submission to that inquiry11 focused on systemic issues recurring in complaints, including:

- assessment of applications for housing or transfer

- timeliness and delays in allocating housing to eligible applicants

- energy efficiency of older public housing stock

- dissatisfaction with quality and timeliness of maintenance works.

EDUCATION AND TRAINING DIRECTORATE

Overview

The Education and Training Directorate delivers education services through government schools, registers non-government schools, and administers vocational education and training in the ACT.

The directorate’s responsibilities include:

- education (including early childhood education)

- government and non-government schools

- vocational education and training

- higher education.

The administrative activities of the Education and Training Directorate encompass higher education, school-age and early childhood education. The Canberra Institute of Technology and the University of Canberra are not part of the administrative unit of the Directorate. Therefore, the Director-General has no direct responsibility or powers delegated by the Minister for Education and Training in respect of the Canberra Institute of Technology Act 1987 and the University of Canberra Act 1989.

If a complaint concerns services to a person under 18 years of age, it is usually outside the ACT Ombudsman’s jurisdiction, as defined under s 5(2)(n) of the ACT Ombudsman Act. Where it is identified that a complaint relates to services to children or young people, the complainant is referred to the ACT Human Rights Commission without investigation. Complaints about administrative services in the ACT’s higher educational institutions, Canberra Institute of Technology and University of Canberra, normally fall within the ACT Ombudsman’s jurisdiction and are considered for investigation. Where a complaint relates to services provided to overseas students attending these institutions, it is referred to the Overseas Students Ombudsman team within the office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman.

Complaints and investigations

In 2011–12, the office received 39 approaches and complaints (5% of the total approaches and complaints) about activities within the Education and Training Directorate, the Canberra Institute of Technology, and the University of Canberra, of which seven were investigated. The issues in these complaints included an internal investigation into the conduct of a teacher, academic appeal procedures, and reporting of non-compliance with student visa conditions to the Department of Immigration and Citizenship. Five of these complaints were finalised by providing a better explanation of the process to the complainant. The agencies were asked to reconsider decisions in the remaining two complaints.

Table 14: Approaches and complaints received about the Education and Training Directorate 2011–12

| EDUCATION AND TRAINING | RECEIVED | FINALISED | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | NOT INVESTIGATED | INVESTIGATED | TOTAL | |

| Education and Training Directorate | 14 | 12 | 1 | 13 |

| University of Canberra | 14 | 13 | 1 | 14 |

| Canberra Institute of Technology | 11 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| 39 | 35 | |||

- 9http://www.legassembly.act.gov.au/downloads/submissions/6.%20ACT%20Ombudsman.pdf.

- aThe Directorate has advised that as ACT TAB is a Government owned corporation, the Directorate has no administrative responsibility for this agency.

- 10http://ombudsman.act.gov.au/files/investigation_2012_01.pdf.

- 11http://www.parliament.act.gov.au/downloads/submissions/Sub%2011%20ACT%20Ombudsman. pdf.

ACT Policing

Overview

In the ACT, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) undertakes community policing governed by an agreement between the Commonwealth and the ACT Governments. The AFP provides policing services to the ACT in areas such as traffic law, crime prevention, maintaining law and order, investigating criminal activities and responding to critical incidents.

Complaints about the AFP are dealt with by the AFP under the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (AFP Act) (Cth) and may also be investigated by the Ombudsman under the Ombudsman Act 1976 (Cth). The Ombudsman does not oversight the AFP’s handling of every complaint, but is notified by the AFP of complaints it receives which are categorised as serious conduct issues (Category 3 issues). The Ombudsman reviews these complaints annually.

If a complainant is not satisfied with the outcome of the AFP’s own investigation, the person can complain to this office which then decides whether to investigate the matter.

Complaints made about the AFP and its officers acting in their ACT Policing role are dealt with by the Law Enforcement Ombudsman under Commonwealth jurisdiction and through an agreement with the ACT Government.

The Law Enforcement Ombudsman is also the ACT Ombudsman and the Commonwealth Ombudsman.

The Ombudsman also does an annual review of how the AFP handles ACT Policing complaints and reports this to the AFP Commissioner and the ACT Chief Police Officer.

Complaints and investigations

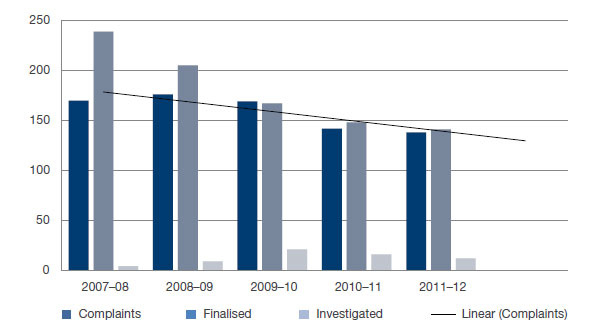

In 2011–12 we received 138 approaches and complaints about the actions of AFP members in their ACT Policing role. This is a reduction of four from 2010- 11 and Figure 4 illustrates this ongoing downward trend. The most common complaint topics were about:

- inappropriate action (46)

- customer service (26)

- police practices (22)

- police misconduct (minor 8, serious 7)

- use of force (8).

Some of the complaints also related to the adequacy of AFP investigations, failure to act and unreasonable delays in investigating complaints. Eight complaints were out of our jurisdiction to investigate as they were employment related matters.

Figure 4: AFP complaints received, investigated and finalised, 2007–08 to 2011–12

The ACT Ombudsman’s office receives many more approaches and complaints than it investigates – in 2011-12 the office finalised 141 approaches and complaints with 91 per cent of these being finalised within three months. Eighty-four of these were referred back to the AFP as the complainants had not first approached that agency. In 10 cases, complainants were advised to pursue their issues in a court or to contact a more appropriate agency for their matter, such as the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity for corruption-related matters. The number of approaches and complaints has gradually declined from 2007-08 (over 150) and the number investigated by the ACT Ombudsman has increased.

In 2011–12, we finalised 141 approaches and complaints with 91% of these being finalised within 3 months. As is our usual practice with complaints, we referred 84 of these back to the AFP as the complainants had not previously approached that agency to seek resolution of their concerns. In 10 cases, we advised the complainants to pursue their issues in a court or to contact a more appropriate oversight agency, such as the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI) for corruption related matters.

We decided not to investigate 35 of the approaches and complaints, for reasons such as:

- an investigation was not warranted in all the circumstances12

- the matter was in the process of being considered by a court

- the matter was out of jurisdiction, such as employment related matters

- the matter was being considered by the Minister

- the complainant was aware of the matter more than 12 months before approaching the Ombudsman.

Of the 12 complaints we did investigate, two issues were about excessive use of force on an individual, two were about unwarranted police attention, four were about inappropriate action, two were about minor misconduct and two about property retained by the AFP.

We were critical of the AFP in two cases—one, where in our opinion, the AFP’s investigation of a complaint was poorly handled. In this case we came to the view that a potential conflict of interest by the main investigating officer had resulted in an incorrect decision. There was also a long delay in finalising this complaint, particularly in relation to the time ACT Police took to return seized money to the complainant (refer Case study 10: Conflict of interest inappropriately managed). In the other case we found there was an unreasonable delay (of almost 20 months) in investigating the complaint.

Table 15: Approaches and complaints received about ACT Policing 2011–12

| ACT POLICING | RECEIVED | FINALISED | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | NOT INVESTIGATED | INVESTIGATED | TOTAL | |

| ACT Policing | 138 | 129 | 12 | 141 |

| 138 | 141 | |||

Case Study 10

Conflict of interest inappropriately managed

Mr X complained to our office that during a search of his residence, ACT Policing members accessed a store room and garage that were not included on the original warrant. Once ACT Policing members accessed the storeroom and garage, they sought an amended warrant from a Magistrate which included the two structures. During the execution of the search warrant, a large amount of money and other items suspected of being stolen were seized.

Mr X made a complaint to AFP Professional Standards (PRS), and one of the officers who assisted in the execution of the search warrant at Mr X’s residence, Sergeant A, was appointed as the investigating officer by the ACT Complaint Management Team (CMT). The CMT investigation found Mr X’s complaint not established. Mr X then approached our office, as the money had not yet been returned and he was unhappy with Sergeant A’s investigation.

Our office investigated the matter and considered the appointment of Sergeant A as the investigating officer was a conflict of interest. In our view, this investigation should never have been allocated to Sergeant A, and that Sergeant A should have declared this potential conflict and declined to investigate the matter when appointed as the investigator.

We also found that the outcome of the investigation was flawed and that the seized money should have been returned to Mr X in a timelier manner. Our investigation found that it was likely that the original search warrant only included the search of Mr X’s unit and not the associated structures at the residence. Our view was that the amended warrant should have been obtained prior to the storeroom and garage being accessed. We recommended that the AFP provide an apology to Mr X.

In response to our criticism, the AFP initiated an internal investigation into the execution of the search warrant and the subsequent complaint investigation conducted by Sergeant A. PRS also advised that it would discuss ACT Policing providing an apology to Mr X with the Chief Police Officer of ACT Policing.

As a result of our investigation, PRS raised a complaint against Sergeant A and has advised our office that serious misconduct was established against Sergeant A. The AFP has also sought to reinforce with all staff the importance of identifying and managing conflicts of interest.

As a result of another (unrelated) complaint that was investigated by our office, the AFP has reviewed its handling of conflict of interest and complaint management. The AFP has advised that no matters are to be assigned to AFP members for investigation who have had any involvement in the original incident, unless the involvement was supervisory in nature and any conflict of interest is identified and can be reasonably managed.

The Ombudsman has continued to highlight the importance of the AFP complaint management practices being both transparent and seen to be above reproach to the integrity of the police in the eyes of the community. It is essential that the processes of investigation and internal review recognise that the public perception of the police can be compromised if a customer-centred approach to complaints is not taken.

Table 16 shows the remedies we provided or recommended from our investigation of 12 complaints. A total of 27 issues were recorded across the 12 complaints investigated.

Table 16: Remedies for investigated complaints about ACT Policing 2011–12

| TYPE OF REMEDY | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|

| Action expedited | 11 |

| Apology | 15 |

| Decision changed or reconsidered | 11 |

| Disciplinary action | 7 |

| Better explanation provided | 33 |

| Financial remedy | |

| Other non-financial remedy | 22 |

| Remedy provided without Ombudsman intervention |

Other remedies achieved in complaints we investigated included:

- recommending that the AFP apologise to the complainant and provide a better explanation of its actions

- providing a better explanation to the person concerned for example, in one case we explained to the person how they could collect their seized property directly from the AFP

- requesting the AFP re-examine a case due to new evidence obtained by us through interviewing the complainant (refer Case study 11)

Case Study 11

Inadequate investigation

Ms X complained to our office that ACT Policing had not charged her ex‑husband, Mr Z, with breaching a Domestic Violence Order (DVO) that had been issued by the ACT Magistrates Court. Ms X stated that following her separation from Mr Z, she had remained in their residence which was owned by Defence Housing Australia (DHA). While Ms X was moving out of the DHA residence Mr Z attended the residence, in contravention of the DVO that stated that Mr Z could not attend the DHA residence while the DVO was in force. Ms X contacted ACT Policing to report the alleged DVO breach, but was told that Mr Z had not breached the DVO and ACT Policing would not take action in the matter.

Ms X made a complaint to AFP Professional Standards (PRS), and the complaint was referred to the ACT Complaint Management Team (CMT) for investigation. The CMT investigation found Ms X’s complaint not established, as the investigator was of the view that Mr Z had not breached the DVO, and the ACT Policing members who spoke with Ms X had acted reasonably.

Ms X then approached our office because she was unhappy that the AFP would not charge Mr Z with a breach of the DVO.

We investigated the matter and found that ACT Policing had contacted Mr Z in response to Ms X’s allegations of Mr Z breaching the DVO. Mr Z told ACT Policing that DHA had advised him that Ms X had vacated the residence. ACT Policing accepted the statements of Mr Z and did not contact DHA to confirm the details Mr Z provided. However, when we contacted DHA to confirm the details that Mr Z had provided to ACT Policing, DHA advised our office that they had not provided Mr Z with any details about Ms X vacating the property.

We found that ACT Policing had failed to exercise due diligence during its investigation of Ms X’s allegation that Mr Z breached the DVO because they had failed to contact DHA to confirm the accuracy of the details provided by Mr Z. It was our view that had ACT Policing contacted DHA, it would have led to ACT Policing questioning the accuracy of Mr Z’s statements, and this may have resulted in a different outcome to Ms X’s allegation of a DVO breach. We also suggested that ACT Policing apologise to Ms X for failing to exercise due diligence when investigating her criminal allegation and complaint.

Review of complaint handling

The Ombudsman has an obligation under s 40XA of the AFP Act to review the administration of the AFP’s handling of complaints through inspection of AFP records. This includes records of the handling of complaints about ACT Policing. The Ombudsman reports to the Commonwealth Parliament annually, commenting on the adequacy and comprehensiveness of the AFP’s handling of conduct and practices issues, and inquiries ordered by the relevant Minister. Our annual report on the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s activities under Part V of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 covered the period 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2011 and was tabled in Parliament in November 2011. This report dealt with one review (Review 7) of AFP complaint records that we undertook in that period. The report is available on the Ombudsman’s website (www.ombudsman.gov.au).

We are currently finalising our Review 8 report and note some improvement in the timeliness of complaint handling by the AFP, particularly in the finalisation of complaints over two years old. We also continued to draw attention to the need for the AFP to better use the information provided by complainants to determine and address systemic problems.

We continue to take a close interest in complaints about the AFP’s use of force and have taken the opportunity to observe AFP training in this area. This assists us to better understand how policies are put into operational practice and can also help us to better understand the information we get from police when we investigate complaints. Further details on our findings and the AFP’s response can be found in the most recent report to the Parliament, available on our website (www.ombudsman.gov.au).

Of the 553 conduct issues raised in complaints to the AFP during the review period 2010-11, 52% related to ACT Policing. This is consistent with ACT Policing being the area of the AFP with the greatest contact with members of the public. This figure has reduced from the previous period when 62% related to ACT Policing.

Of these, the AFP considered 14% ‘established’ (substantiated) which is an increase from the nine per cent for the last reporting period.

Our review of complaints finalised within 2011–12, Review 8, will be tabled in Parliament in late 2012.

Other significant engagement

Critical incidents

The AFP notifies the Ombudsman of critical incidents involving ACT Policing. Critical incidents are incidents in which a fatality or significant injury has occurred, or where the AFP has been required to respond to an incident on a large scale, as might occur during a public demonstration. Usually we do not get involved in the investigation of critical incidents unless the AFP requests our involvement. The AFP provides a briefing to the Ombudsman so the office can keep a watching brief on the more serious incidents that arise in the ACT involving the AFP.

During 2011–12, the AFP notified our office of one critical incident that occurred in the ACT. This incident involved a vehicle hitting two pedestrians near Canberra Hospital both of whom were employees of the hospital. One pedestrian died and this incident was widely covered in the ACT press. The AFP is currently reviewing this incident and will provide a copy of its final report to us when available.

Stakeholder engagement, outreach and education activities

The AFP hosted the annual AFP/ Ombudsman Forum in July 2011. The forum is a valuable opportunity to discuss relevant issues that arise through the work of both agencies, to exchange information and ideas on ways to improve the AFP’s complaint handling processes. This year we considered the AFP Categories of Conduct which is a legislative instrument determined jointly by the AFP Commissioner and the Ombudsman under the AFP Act. It forms the basis for AFP investigations of complaints against members. We also considered new more simplified procedures for handling the less complex complaints so that a result can be provided to the complainant in a timelier manner.

The Ombudsman Law Enforcement Team engaged in outreach and stakeholder activities during the year to discuss the role of the Ombudsman and our complaint handling procedures. This assists people to understand how they can make a complaint. Outreach during this period included:

- presenting at a Legal Workshop for first year law students at the Australian National University. Feedback from the workshop indicated that attendees found the information provided very helpful.

- attending an orientation session for new members of the Australian Federal Police Professional Standards. This provides us with the opportunity to make new members of PRS and AFP Complaint Management teams aware of our role in managing complaints about AFP members.

- in June 2012, our office facilitated a Community Group Forum where issues of concern were discussed.

Additionally, law enforcement staff observed new ACT Policing recruits undertaking their operational safety training in July and August 2011. The operational safety training involves training the new recruits in the appropriate use of force and covered use of firearms, OC spray, batons and escort holds and takedowns. The course also covered appropriate communication techniques.

In August 2011, law enforcement staff were provided with a demonstration of non-lethal AFP weapons used during an incident on Christmas Island in March 2011 so we could understand the practical use of these weapons and the impact they may have on an individual.

Taser reporting

We currently have an informal arrangement in place with AFP Professional Standards (PRS) to provide our office with Use of Force (UoF) reports relating to incidents involving the use of tasers by ACT Policing and have been provided with UoF Reports from 1 January 2011 to 31 March 2012. We have an oversight function and analysed these reports and are in the process of drafting a report for comment by ACT Policing. We have not decided whether to make this report public at this time.

- 12The Ombudsman has the discretion to decline to investigate a matter where ‘investigation is not warranted in all the circumstances’. Most commonly, we will exercise this discretion where it is clear that the agency has already provided the complainant with a reasonable outcome or remedy to the complaint.