Section A: Performance and financial management reporting

Section A: Performance and financial management reporting

- Introduction

- The organisation

- Overview

- Highlights

- Outlook for 2009–10

- Analysis of agency performance

- Complaints—ACT Government Agencies

- Complaints—Policing

- Inspections—Policing

Introduction

The office of the ACT Ombudsman was established 20 years ago when self-government came into effect for the ACT. On 19 November 1990, Prof. Dennis Pearce, the first ACT Ombudsman, submitted the first annual report to the Legislative Assembly about the operation of the newly established office. Since then there have been significant changes in the office that reflect the growth in our community and the expansion of services delivered by ACT Government agencies.

In our first annual report (1989–90) we reported that we had received 367 complaints, covering the full range of activities carried out by the ACT Government. In addition, we received 269 complaints about the Australian Federal Police (AFP) in its ACT Policing role. That total of 636 complaints is not dissimilar to today. In 2008–09 we received 722 approaches and complaints about the actions of ACT Government agencies and ACT Policing. However, the proportion of complaints has changed. We now receive around 500 to 550 approaches and complaints about ACT Government agencies, and about 150 to 200 about ACT Policing. The lower number of complaints about ACT Policing reflects legislative changes that took place at the end of 2006, such that the Ombudsman no longer has oversight of the handling of all complaints about the AFP.

The nature of the complaints received has changed over the years, although some issues remain uncannily similar. In our first annual report, we highlighted an increase in the number of parking complaints.1 The Ombudsman at the time formed the view that the increase in complaints was due to increased numbers of parking inspectors patrolling the city, heavier fines that encouraged people to dispute rather than pay the fine, and fewer free parking spaces, particularly in the centre of Canberra. We still receive these types of complaints, although a decrease in the number probably shows that people are less inclined to dispute an infringement notice.

Since 1989 other statutory oversight bodies have been established in the ACT with responsibility for investigating some actions of ACT Government agencies. These oversight bodies include the Commissioner for the Environment and the Human Rights Commission. The capacity for oversight bodies to investigate complaints about ACT Government agencies is an important step in ensuring that the agencies act reasonably and fairly when delivering services and dealing with the ACT community.

The organisation of this office has also changed over time in response to the needs of the ACT community. In June 2004, we celebrated our fifteenth anniversary. We officially launched the ACT Ombudsman shopfront and held our first annual contact officers seminar. The shopfront is still with us today and our Public Contact Team (PCT) operates as the first point of call to receive all approaches from the ACT community about the actions of ACT Government agencies.

1 The comparison was with the period before self-government, when the Commonwealth Ombudsman had jurisdiction over complaints about ACT agencies.

The Organisation

The role of the ACT Ombudsman is performed under the Ombudsman Act 1989 (ACT). The Ombudsman also has specific responsibilities under the Freedom of Information Act 1989 (ACT) and the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (Cth), and is authorised to deal with whistleblower complaints under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1994 (ACT).

The Commonwealth Ombudsman, who is appointed under the Ombudsman Act 1976 (Cth), discharges the role of ACT Ombudsman under the ACT Self-Government (Consequential Provisions) Act 1988 (Cth).

Up until 30 December 2006 the Ombudsman also had specific responsibilities in relation to the AFP under the Complaints (Australian Federal Police) Act 1981 (Cth). Complaints made about the AFP before 30 December 2006 continue to be dealt with under that Act. Complaints made after that date are dealt with under the Ombudsman Act (Cth). In addition, the Ombudsman has a role in monitoring compliance with chapter 4 (Child Sex Offenders Register) of the Crimes (Child Sex Offenders) Act 2005 (ACT) by the ACT Chief Police Officer and other people authorised by the Chief Police Officer to have access to the register.

The ACT Ombudsman is an independent statutory officer who considers complaints about the administrative actions of government departments and agencies. The Ombudsman aims to foster good public administration by recommending remedies and changes to agency decisions, policies and procedures. The Ombudsman also makes submissions to government on legislative and policy reform.

The office investigates complaints in accordance with detailed written procedures, including relevant legislation, a service charter and a work practice manual. It carries out complaint investigations impartially, independently and in private. Complaints may be made by telephone, in person or in writing (by letter, email or facsimile, or by using the online complaint form on our website). Anonymous complaints may be accepted.

The key values of the ACT Ombudsman are independence, impartiality, integrity, accessibility, professionalism and teamwork.

Our clients and stakeholders cover all people who may be affected by the administrative actions of ACT Government agencies and the AFP in carrying out their ACT Policing role.

A services agreement between the ACT Government and the Ombudsman covers the provision of services in relation to ACT Government agencies and ACT Policing.

In 2008–09 the Ombudsman delegated day-to-day responsibility for operational matters for the ACT Ombudsman to Senior Assistant Ombudsman Anna Clendinning, and responsibility for law enforcement, including ACT Policing, to Senior Assistant Ombudsman Diane Merryfull. Both Senior Assistant Ombudsmen are supported by a team of specialist staff (the ACT Team and the Law Enforcement Team respectively) in carrying out these responsibilities for the Ombudsman. The Ombudsman and Deputy Ombudsmen maintain an active involvement in the work of these two teams.

Overview

Complaint statistics

Complaint handling remains the core of the ACT Ombudsman's role. In 2008–09 we received 722 approaches and complaints about the actions of ACT Government agencies (546) and ACT Policing (176). This was almost the same as –08 when the office received 711 approaches and complaints (541 about ACT Government agencies and 170 about ACT Policing).

Housing ACT and ACT Corrective Services (ACTCS) continue to be the agencies that are the subject of the majority of complaints that we receive (135 and 119 respectively in 2008–09). The numbers of complaints about these agencies are not necessarily an indication that they are not performing well, but a reflection of the nature of the role and responsibilities that each agency plays in the community.

During the period we finalised 742 approaches and complaints, 537 of which were about ACT Government agencies and 205 about ACT Policing.

Detailed analysis is provided in the 'Performance' section of this report under the headings 'Complaints—ACT Government agencies' and 'Complaints—ACT Policing'.

Submissions and major investigations

An important role of the Ombudsman is to contribute to public discussion on administrative law and public administration and to foster good public administration that is accountable, lawful, fair, transparent and responsive.

To achieve this outcome, we made submissions to, or commented on, a range of administrative practice matters, cabinet submissions and legislative proposals during the year. These included:

- a submission to the Standing Committee on Administration and Procedure inquiring into the appropriate mechanisms to coordinate and evaluate the implementation of the Latimer House Principles in the governance of the ACT

- input into the ACT Government's response to the Commonwealth Attorney-General's Department about the report on the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

- a submission to the ACT Department of Justice and Community Safety on the review of the Victims of Crime Act 1994.

We are also participating in a project funded by the Australian Research Council—Applying human rights legislation in closed environments: a strategic framework for managing compliance. This project is particularly relevant to the operation of prisons from a human rights perspective and is being led by a research team based at Monash University, Melbourne.

In last year's annual report we noted that the draft report of the own motion investigation about the adjudication of breaches of discipline at the Belconnen Remand Centre and Symonston Temporary Remand Centre had been provided to the ACTCS for comment prior to finalisation. The report has been published and is available on our website at www.ombudsman.act.gov.au.

In October 2008 the Ombudsman completed an own motion investigation into the AFP's use of powers under the Intoxicated People (Care and Protection) Act 1994 (ACT). The report is available on the Commonwealth Ombudsman website at www.ombudsman.gov.au, and further details are in the 'Performance' section of this report under the heading 'Complaints—ACT Policing'.

In January 2009 an incident occurred at the Belconnen Remand Centre that involved an altercation between detainees and custodial staff. We are conducting an own motion investigation into the incident. Our investigation concerns strip searching and segregating detainees, conducting cell searches and dealing with detainees' personal property within the confines of a correctional facility. We expect to complete the investigation later in 2009 and will advise of the outcome in our annual report for 2009–10.

Organisational planning and environment

The office's strategic plan for 2008 to 2011 sets out the office's direction for that period. Each year the Ombudsman and Deputy Ombudsmen review the plan and establish the priorities for the next year. Our strategic priorities for 2009–10 are to:

- target outreach, relevant publications and communication activities to key stakeholders, particularly in regional Australia

- identify, through individual complaint investigation, problem areas in public administration that occur across government

- be responsive to areas of changing need in allocating resources

- implement a new electronic records management system to improve recordkeeping, consolidate new quality assurance and utilise the growing data the new system is delivering to improve the quality of our complaint handling

- further develop staff training and development programs

- enhance services over the internet, including improved opportunities to lodge complaints via the web.

Detailed reporting against the priorities for 2008–09 is provided in our Commonwealth Ombudsman Annual Report, available online at www.ombudsman.gov.au.

Some specific highlights, discussed elsewhere in this report, include the publication of the Ombudsman's Better Practice Guide to Complaint Handling, the implementation of a range of improvements to our work practices, partly in response to the analysis of the results of a client survey conducted late in 2007–08, and the introduction of further quality assurance processes in the office.

Highlights

Complaints service

The PCT manages all approaches that we receive in the office. The ACT Team provides training sessions to new PCT staff on the jurisdiction of the ACT Ombudsman. The ACT Team also provides continuous training to PCT staff about the role and responsibilities of the ACT Ombudsman. This ensures that approaches to the office are efficiently and effectively handled in the first instance. In circumstances where an approach is not within jurisdiction, the PCT provides guidance and contact details for other agencies that may assist the complainant, such as the Health Services Commissioner.

Periodically the office surveys complainants, as this is one way to measure our performance and to identify areas for improvement in service delivery. Such surveys also provide information that helps us to better target our outreach activities.

Late in 2007–08 we commissioned an independent market research company to undertake a survey of complainants. The survey aimed to obtain information on three key aspects—access, demographics and quality of service. We surveyed 2000 people who had made a complaint about an Australian Government or ACT Government agency.

Overall the level of satisfaction with the Ombudsman's office across the office's Commonwealth and ACT jurisdictions increased from 58% in our last survey (conducted in 2004) to 60%. For people whose complaint we investigated, overall satisfaction fell from 64% to 57%. There was a high correlation between their overall satisfaction with the office and their satisfaction with the result of the office's investigation. However, the level of satisfaction for people whose complaint we did not investigate increased from 54% to 62%.

The majority of the people surveyed considered we kept them well informed about our handling of their complaint, and rated the courtesy of our staff highly. The majority of respondents considered we dealt with their complaint in about the right time, or in less time than they had expected. They also considered we understood the critical issues in their complaint. While our staff were perceived as being clear in communication, and professional and ethical, around one-fifth of respondents considered our staff were not independent or impartial.

Partly as a result of the survey, we are implementing a range of strategies to improve our services further. They include:

- incorporating more communication training in our core training modules

- creating scripts to be used by our public contact officers

- reviewing our template letter

- redesigning our internet sites

- reviewing how we manage approaches to the office.

We have also introduced a comprehensive quality assurance program to complement the oversight line managers give to the handling of complaints. A panel of experienced senior investigation officers from across the office, led by a Deputy Ombudsman, audit a sample of complaints closed each month. This panel provides feedback to the staff who handled the complaints and, where necessary, their manager. The panel also produces a report identifying areas for improvement in complaint handling, as well as best practice examples they have seen. This is part of a more comprehensive quality assurance process that includes normal supervision, a capacity to require more senior sign-off as part of our complaint management system, peer or supervisor checking of all correspondence, our system of case reviews and our complaint and feedback processes (including complainant surveys).

Public administration and complaint handling

The ACT Ombudsman continues to contribute to improvements in public administration by participating in specific projects, investigating and resolving complaints from individuals and identifying systemic problems in public administration.

The Commonwealth Ombudsman published the Better Practice Guide to Complaint Handling in April 2009. The guide builds on previous Ombudsman publications by defining the essential principles for effective complaint handling, and can be used by agencies when developing or evaluating their complaint-handling systems. It can also be used by ACT Government agencies to improve internal complaint-handling systems.

We continued to have regular liaison meetings with ACT agencies and with agency contact officers. These meetings assist in maintaining a good working relationship with agencies which is important for timely and effective resolution of complaints.

We have provided significant input into ACT Government initiatives during the year, including participation in the following projects organised by the Department of Justice and Community Safety:

- the ACT Prison project

- the Human Rights Working Group

- the Victims of Crime Reference Group.

We also provided feedback to the Department of Justice and Community Safety on the implementation of the Foundation for Effective Markets and Governance recommendations. This project was initiated in 2004 to review the system of statutory oversight of government in the ACT.

Under s 40XA of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (Cth), the Ombudsman, as Commonwealth Ombudsman, has a responsibility to review the administration of the AFP's handling of complaints, through inspection of AFP records. This includes records of the handling of complaints about ACT Policing. Further details are in the 'Performance' section of this report under the heading 'Complaints—ACT Policing'.

Outlook for 2009–10

We will continue a program of contact officer forums for ACT Government agency complaint contact officers, including a special forum to celebrate 20 years of the ACT Ombudsman.

We actively encourage agencies to seek our participation in their internal training sessions. As a result of closer involvement in training programs, this office will be able to develop training aids that target the information needs of ACT Government agencies about the functions of the Ombudsman. We will also be able to target information sessions based on the specific issues relevant to the individual agencies.

We will promote the Better Practice Guide to Complaint Handling in the ACT Government sector as a valuable tool for agencies to use in the establishment and review of agency complaint-handling procedures.

The new prison in the ACT, the Alexander Maconochie Centre (AMC), was officially opened on 11 September 2008. From March 2009, ACT detainees from the ACT and other correctional facilities in NSW have moved into the facility. In June 2009 more than 160 remandees and sentenced prisoners were accommodated in the AMC. The AMC has been designed from a human rights perspective, catering for all levels of detainee security classifications. We will monitor complaints from detainees and keep the ACTCS informed of any emerging trends or systemic issues that may arise.

Analysis of agency performance

Summary of performance

In 2008–09, the ACT Government paid an unaudited total of $983,569 (including GST) to the Ombudsman's office for the provision of Ombudsman services.

The Ombudsman is funded under a services agreement with the ACT Government which was signed on 31 March 2008. Payments (including GST) were for the purposes of the Ombudsman Act 1989 (ACT) ($463,011) and for complaint handling in relation to ACT Policing ($520,558).

The office's performance against indicators is shown in Table 1 and provided in more detail under the headings 'Complaints—ACT Government agencies', 'Complaints—ACT Policing' and 'Inspections—ACT Policing'. The statistical report in Appendix 1 provides details of complaints received and finalised, and remedies provided to complainants, in 2008–09.

Table 1 Summary of achievements against performance indicators, 2008–09

Performance indicator | ACT Government agencies | ACT Policing |

|---|---|---|

Number of approaches and complaints received | 546 approaches and complaints | 176 approaches and complaints (170 in 2007–08) |

Number of approaches and complaints finalised | 537 approaches and complaints | 205 approaches and complaints (239 in 2007–08) |

Time taken to finalise complaints | 93% of all complaints finalised within three months (87% in 2007–08) | 96% of complaints finalised under the Ombudsman Act (Cth) within three months (92% in 2007–08) |

The categories of approaches and complaints to this office range from less complex approaches that can be resolved with minimal investigation to more complex matters requiring the office to exercise its formal statutory powers. In all approaches that require investigation by this office, we contact the agency to find out further information about the complaint and to give the agency an opportunity to respond to the issues raised in the complaint. Often an approach from this office to the agency will assist in resolving the complaint in the first instance.

Where a complaint involves complex or multiple issues, we conduct a more formal investigation. The decision to investigate a matter more formally can be made for a number of reasons:

- a specific need to gain access to agency records

- the nature of the allegations made by a complainant require records to be provided

- if there is likely to be a delay in the time taken by an agency to respond to our requests for information

- the likely effect on other people of the issues raised by the complainant

- the agency requests that formal powers are used in an investigation.

Not all of the approaches we receive are complaints that are within the jurisdiction of the Ombudsman. We refer people to other oversight agencies that are established to handle specific types of complaints such as the Human Rights and Discrimination Commissioner and the Health Services Commissioner. There are some issues that are not within the jurisdiction of the Ombudsman, such as employment-related matters or decisions of courts or tribunals. In these cases, we inform the person of the limits of our jurisdiction and the role of the Ombudsman. We try to provide relevant information and contact details to assist them.

Liaison and training

This office aims to develop a better understanding by the public and by agency staff of the role and responsibilities of the Ombudsman. We engage in community outreach activities that assist to promote this better understanding. In 2008–09 this included:

- promoting the ACT Ombudsman role to students during Orientation Week activities at the Australian National University, the University of Canberra and the Canberra Institute of Technology

- participating in Law Week with a stall at the Law Market day in Civic

- conducting a complaint clinic at the Aboriginal Justice Centre

- promoting the role of the Ombudsman at the ACT Multicultural Festival.

Ombudsman staff participated in formal and informal meetings with ACT Government agencies and conducted information and training sessions throughout the ACT Government sector. This liaison and training is important for the effective and efficient conduct of our complaint investigation role. Activities included:

- information sessions as part of the induction of ACTCS custodial and non-custodial staff

- input to the ACT Prison Project and the Human Rights Working Group organised by the Department of Justice and Community Safety

- regular meetings with senior staff in ACT Government agencies to provide feedback on complaints received and to ensure smooth handling of complaints

- training sessions with the staff of Canberra Connect, the call centre that is the gateway to ACT Government agencies and services

- input into an ACT Mental Health brochure about the complaint-handling role of the ACT Ombudsman

- an information session with the senior complaint-handling staff of the ACT Planning and Land Authority.

We also gave a presentation to a delegation from the Ministry of Justice of the People's Republic of China about the role of the Ombudsman, particularly in relation to detainees in the custody of the police or being accommodated in correctional facilities.

Service charter standards

The ACT Ombudsman Service Charter sets out the standards of service that can be expected from this office, explains how complainants can assist us to help, and provides complainants with an opportunity to comment on our performance.

We regularly monitor our performance against the service charter standards and assess ways to promote further improvement.

The feedback from complainants enables us to improve our service. The service charter is available on our website at www.ombudsman.act.gov.au.

As noted above, we analysed the results of a client satisfaction survey conducted in late 2007–08, and put in place a range of initiatives to deal with the issues identified through that survey and other forums.

If a complainant disagrees with the conclusions on a complaint, they can request a review. The reasons for seeking a review should be provided as this assists the office to fully understand the complainant's concerns.

Late in 2008–09 we introduced a new approach to dealing with requests for reviews.

Under this new approach, a centralised team considers first whether a review should be undertaken, and then conducts the review if required. In some cases, discussion with the person seeking a review may indicate that the person needs a clearer explanation of information we have already provided, or has misunderstood our role, and further investigation is not necessary. The aim of the changes is to provide greater consistency and timeliness in undertaking reviews.

One important factor we take into account in deciding whether we should investigate further is whether there is any reasonable prospect of getting a better outcome for a person. This helps ensure that the office's resources are directed to the areas of highest priority. If, as a result of a review, investigation or further investigation is required, the review team allocates the complaint to a senior staff member who decides who should undertake the investigation or further investigation.

During 2008—09 we dealt with 15 requests for reviews. Thirteen of the requests related to ACT Government agencies and two involved ACT Policing. In 11 cases the original decision was affirmed. In four cases, the complaint was referred back to the relevant team for investigation or further investigation.

COMPLAINTS—ACT Government Agencies

Complaints received

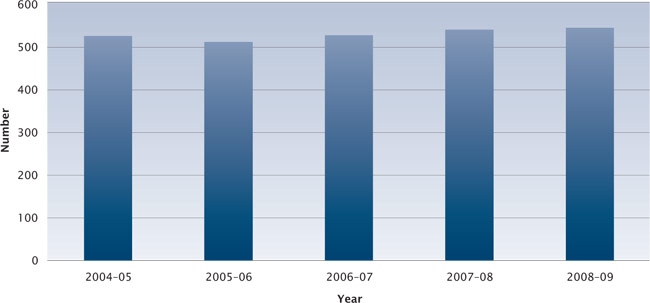

In 2008–09 we received 546 approaches and complaints about ACT Government agencies, virtually the same as in 2007–08 (541). Figure 1 provides a comparison of approaches and complaints received about ACT Government agencies since 2004–05.

Figure 1 Approaches and complaints received about ACT Government agencies, 2004–05 to 2008–09

Housing ACT and the ACTCS are the agencies that are the subject of the majority of approaches to this office.

We received 135 approaches and complaints about Housing ACT, which is an increase of 35% over the number received in 2007–08 (100). Housing ACT interacts with a significant portion of the community as it operates to provide and maintain public housing for the more vulnerable members in our community.

Meeting the housing needs of our community requires the agency to work within the current capacity of available housing and make decisions about allocations and maintenance issues that have a significant impact on the daily lives of community members. Considerations for aged, disability and health care management may be just some of the interlinking issues they must take into account in a housing allocation or maintenance issue.

We recognise the complexities that Housing ACT must deal with to fulfil its role and responsibilities in the community. We consider that this office has an integral role in ensuring that the agency operates fairly and reasonably in the conduct of its business.

We received 119 approaches and complaints about the ACTCS, compared to 155 in 2007–08. Issues regarding the ACTCS, and in particular the Belconnen Remand Centre, are addressed later in this section.

Complaints finalised

During 2008–09 we finalised 537 approaches and complaints about ACT Government agencies, compared to 561 approaches and complaints in 2007–08. This year we investigated 30% of the complaints we finalised, compared to 33% last year.

In most cases we decided not to investigate because the complainant had not tried to resolve their problem first with the relevant agency. This practice of referring complainants back to the agency concerned in the first instance provides the agency with the opportunity to resolve any issues before an external body, such as the Ombudsman, becomes involved.

The remedies for complaints we investigated included penalties or debts being waived or reduced, agency actions expedited, agency apologies, decisions changed, and better explanations by agencies.

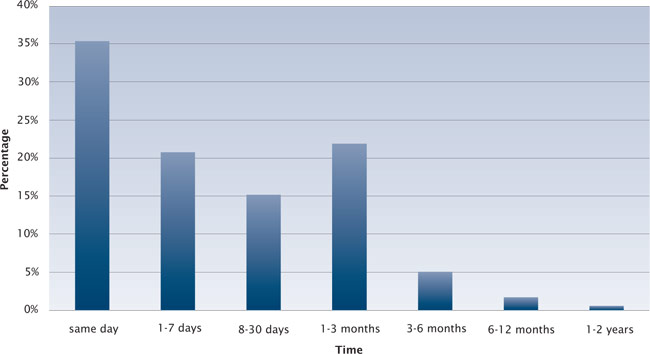

Of the 537 approaches and complaints about ACT Government agencies that were dealt with during 2008–09, 56% were finalised within one week and 93% within three months (see Figure 2). This is slightly better than in 2007–08, when we finalised 55% in one week and 87% in three months.

Figure 2 Time taken to finalise approaches and complaints about ACT Government agencies, 2008–09

Of the remaining approaches and complaints, 5% were completed in three to six months and 2% took more than six months to complete. Complaints that take more than six months to complete are more complex in nature, requiring the extensive involvement of senior staff in the office.

Complaint themes 2008–09

Complaints often raise similar issues in public administration. Although each complaint is unique, common themes can arise when the public is dealing with government agencies. Identifying these themes can assist agencies to assess their public administration style and improve their service to the public.

The main themes identified across ACT Government agencies during 2008–09 were:

- the importance of following sound internal procedures, particularly procedures that flow from legal obligations

- improving communication with the community

- acknowledging mistakes and providing an appropriate remedy.

Following procedures

One of the challenges highlighted in this annual report is for agencies to have proper internal procedures and to follow them.

There are many different types of rules and procedures. In some cases they are stipulated in legislation, or are developed to ensure that agency officers comply with legislative requirements. Non-compliance may lead an agency officer to act unlawfully.

The case study Complying with the law shows how, as a result of our investigation, the ACT Planning and Land Authority (ACTPLA) made a commitment to ensure that officers entering onto private land comply fully with their legal obligations. We encourage agencies to conduct regular compliance audits of agency practices that flow from legal obligations.

Complying with the law

Mr A complained that inspectors from ACTPLA had trespassed on his land without his consent at least twice. We investigated his complaint and found photographic evidence in ACTPLA records that this was the case. ACTPLA inspectors, as a result of checking whether Mr A had complied with an order to clean up his land under the now repealed Land (Planning and Environment) Act 1991, had entered onto Mr A's land to carry out the inspection. The legislation contained entry powers that, if complied with, permitted inspectors to enter land for the purpose of carrying out the inspections. ACTPLA inspectors had not complied with their legal obligations on at least two occasions.

As a result of our investigation ACTPLA has revised its procedures and forms for gaining consent to enter private land and is instituting an ongoing education program within the inspectorate. ACTPLA advised that it would review the practices, procedures and training that apply to inspectors and undertake a compliance audit of inspections.

It is important that agency policies and procedures accurately reflect the legal obligations that the agency and its officers are required to satisfy. To ensure compliance, agencies should have well-trained staff who know and understand their statutory obligations. Such training opportunities should be provided as part of staff induction and as part of an agency's ongoing in-service training commitment for all staff.

The case study Processes and procedures covers the actions of the ACTCS in response to an incident at the Belconnen Remand Centre (BRC). The capacity for the ACTCS to follow internal procedures and respond in a measured way was tested in circumstances that required an urgent response.

Processes and procedures

We received complaints about an incident involving a number of detainees and custodial officers that occurred at the BRC in January 2009. The complaints related to the ACTCS's compliance with internal policies and procedures, and with its statutory obligations under the Corrections Management Act 2007 (CMA). People complained about strip searching and segregation of detainees, as well as the seizure of their personal property.

When we investigated the complaints, we found that ACTCS staff had not properly recorded their decisions and grounds for conducting strip searches of detainees, as required under the CMA. We also found evidence that, as a result of staff searching cells for contraband and weapons and moving detainees to other cells within the BRC, some of the detainees' personal property had not been accounted for and was not returned. We raised this matter with the ACTCS and recommended it implement procedures that reflected the statutory requirements under the CMA for seizing property.

As a result of our investigation, the ACTCS re-affirmed its commitment to following its own procedures for conducting strip searches of detainees. The ACTCS also compensated some detainees for the loss of their personal property and drafted new procedures for staff for handling and removing property from detainees.

Compliance with internal procedures supports the efficient and effective operation of an agency. For example, the procedures may explain legal processes, such as the steps that must be followed before taking a particular action or making a particular decision, the legal requirements concerning recording reasons for a decision or action, or advising a person of any review rights.

Similarly, the procedures may specify the relevant matters to be taken into account in making a decision, and whether they stem from specific legislative requirements or from common principles of good administration, such as the application of natural justice. The procedures may also outline how to deal with financial obligations, both of the agency and of members of the public.

The case study Dealing with matters of discipline demonstrates the strict procedures that the ACTCS is required to follow in conducting a disciplinary investigation of a detainee under the Corrections Management Act 2007 (CMA). This complaint raised issues that were previously raised in our own motion investigation ACT Corrective Services: Discipline adjudications (Report No 01/2008). A copy of this report is available on our website at www.ombudsman.act.gov.au. We have suggested to the ACTCS that we participate in its in-service training of custodial staff. This should assist in addressing issues of compliance with legal obligations under the CMA.

Dealing with matters of discipline

Mr B, a detainee at the BRC, was disciplined under s 134(1) of the CMA for failing to provide a urine sample when directed. A penalty was imposed for this offence. Before it could be carried out, Mr B was also alleged to have committed a further breach of discipline on a drug-related matter. As a result of the second allegation the ACTCS placed Mr B on a 28-day 'special supervision plan' for both breaches.

Our investigation revealed that the investigating officers had not followed their statutory obligations under chapters 10 and 11 of the CMA. There was insufficient recordkeeping to support the outcome of the disciplinary process as recommended by the investigating officer. We concluded that the use of a special supervision plan was not generally supported by the CMA. It was not part of the disciplinary process outlined in chapters 10 or 11 of the CMA, and was not a policy that had been notified in accordance with the CMA. As a result of our investigation, the ACTCS advised that special supervision plans would no longer be used in correctional facilities in the ACT.

Agencies need to ensure that staff have a good working knowledge of their internal procedures in the first instance. This can be achieved by conducting regular training sessions at induction courses and at refresher courses for more experienced officers. Complaints about non-compliance with internal procedures are opportunities for agencies to conduct targeted training opportunities for staff in selected areas of need. The case study Knowing your internal procedures provided an opportunity for the ACT Revenue Office (ACTRO) to provide more training to staff about procedures for handling incoming mail, in part so that financial obligations could be dealt with properly.

Knowing your internal procedures

ACTRO contacted Mr C in July 2008 and advised him that he had an outstanding land tax liability. Mr C objected to the decision. He attempted to lodge his objection by mail with a cheque attached to cover the required fee. Unfortunately the ACTRO mail services did not handle Mr C's letter of objection and cheque properly. As a result, ACTRO did not acknowledge or act on his objection.

Our investigation revealed that the procedure for dealing with incoming mail and land tax objections had not been followed by new staff in the office. ACTRO apologised to Mr C and gave his objection priority attention. ACTRO also advised us that they would review and update the mail-handling process. Existing staff would be asked to re-familiarise themselves with the process and new staff would be trained.

Improving communication with the community

Agencies need to communicate with members of the community in a timely manner. If a person makes a complaint or an enquiry, this contact needs to be acknowledged. This simple step lets the person know that their matter has been accepted and will be handled. In the case study Acknowledging an approach, ACTION failed to respond to an enquiry from a member of the public about bus services in her area. As a result of our intervention, ACTION acknowledged its administrative error and provided the information and statistics that the complainant sought.

Acknowledging an approach

Ms D emailed ACTION about the scheduled bus services in her area, raising concerns about problems with services not being provided on time or not arriving at all. Ms D also wanted some statistics from ACTION about the provision of bus services in the area. She complained to us when she did not get a response after eight weeks.

When we investigated, ACTION acknowledged that due to human error the email had been marked as finalised and closed before any action was taken to acknowledge and respond to Ms D's approach. After discovering the mistake ACTION promptly contacted Ms D and addressed the issues about the bus services in her area.

It is important that the person is kept informed about the progress of their complaint or enquiry, after the initial acknowledgement is sent. Good communication reassures the person that the agency is committed to resolving problems and delivering services. The case study Keeping the complainant informed is an example of an agency neglecting to let the complainants know that it was actively working to resolve their complaint. After our investigation the agency improved its communication with the community member, who subsequently provided positive comments about the agency's customer service.

Keeping the complainant informed

Ms E and her flatmate made several complaints about a neighbour's barking dog to Domestic Animal Services (DAS), a section of the ACT Department of Territory and Municipal Services. The complainants did not think that their complaints were being taken seriously by DAS as they were not informed about any action DAS was taking.

Our investigation revealed that DAS had been working to resolve the situation. It was working within its guidelines for dealing with animal nuisance complaints. However, DAS agreed that it had not kept the complainants informed of its actions.

As a result of our investigation DAS made a commitment to review its complaint-handling procedures. It has emphasised with staff their responsibilities to ensure that people are kept informed of progress with their complaints. Since our investigation Ms E has expressed her appreciation for DAS's ongoing commitment to resolving the complaint and complimented their improvement in customer service.

A complainant is entitled to know how a complaint will be handled and the outcome of actions taken by the agency in response to their complaint. Complaint procedures should ensure that a report on progress is provided if a complaint is not resolved promptly. If there is a delay, the agency should provide an explanation to the complainant. The case study Communication matters shows the importance of an agency informing complainants about its complaint-handling procedures.

Communication matters

Mr F lodged a controlled activity report with ACTPLA about a development taking place on the neighbouring property. He did not receive an acknowledgement of the report. ACTPLA contacted Mr F after eight weeks and informed him that the stop order that had been placed on the development on the neighbour's property was now being lifted. The stop order had been activated as a result of Mr F's report.

We investigated and confirmed that Mr F's report had resulted in a stop order on the development. However, ACTPLA had not advised Mr F of its actions. He was only advised of the outcome of the report when the stop order was lifted.

We concluded that there was unreasonable delay in communicating with Mr F. We considered that ACTPLA should have acknowledged his report and kept him informed about the actions they were taking. Mr F was entitled to have his report addressed by ACTPLA, including an acknowledgement and adequate information regarding its actions.

Acknowledging mistakes and providing an appropriate remedy

If an agency makes an administrative error that adversely affects a person, it should consider providing an appropriate remedy. This is particularly the case if a mistake has caused financial detriment to the person. The case study Compensation required illustrates one such case.

Compensation required

Mr G, a detainee at the BRC, complained that his personal property had gone missing after he was moved to another cell. The missing property ranged from personal toiletry items he had purchased as part of the prisoner buy-up system to items of clothing listed on his property sheet.

We investigated Mr G's complaint. We were disappointed with the ACTCS's initial responses to our enquiries. At first the ACTCS denied that Mr G's personal property had been removed or was missing. After we provided further evidence to support the complaint, the ACTCS asserted that all personal property had been returned and this process had been supervised by a senior ACTCS custodial officer. However, they could not provide documentation supporting the return of Mr G's personal property, including missing toiletries.

We formed the view that this was largely due to the ACTCS not having proper procedures, including recordkeeping procedures, for removing and handling detainee personal property within the confines of a correctional facility. We concluded that there was sufficient evidence to support Mr G's complaint.

As a result of our investigation, the ACTCS credited Mr G's prisoner trust account as compensation for his missing property.

Complaints deliver valuable information from clients about faulty decisions, poor service delivery and defective programs. An agency can use the information from a complaint to provide a suitable remedy and to evaluate and improve procedures and services. In the case study Wrongly charged, Housing ACT was able to use the information provided in the complaint to make improvements to its internal mail procedures.

Wrongly charged

Ms H, a tenant of Housing ACT, complained to our office that a locksmith engaged by Housing ACT had changed the lock to the garage allocated to her flat. Ms H had not asked for this work to be carried out. Housing ACT had raised a debt of $150 against Ms H for the work undertaken. Ms H had been disputing the debt for about five months without success.

We investigated and found that the locksmith had been instructed by Housing ACT to change the garage lock on number 78, but had changed the lock on Ms H's garage at number 87. Housing ACT had misplaced Ms H's initial letter of dispute and taken no action on her complaint.

As a result of our investigation, Housing ACT acknowledged that there had been a mistake and that the debt against Ms H was not appropriate. Housing ACT cancelled the debt and apologised to Ms H. In addition, Housing ACT has improved its incoming mail procedures and now registers all mail to prevent documents being misplaced.

In some cases an agency's actions may be legally correct but may result in a member of the community being treated harshly or unfairly. In these instances, the agency is encouraged to seek alternative outcomes that address the agency's requirements and are fairly applied to the complainant's circumstances. In the case study Negotiating a better outcome, we encouraged the agency and the complainant to consider options that could satisfy both parties.

Negotiating a better outcome

Artists had occupied an ACT Property Group (ACTPG) property for about 15 years without a formal tenancy agreement. The space was used as a studio in which the artists developed their work. In April 2007 the ACTPG, which had recently taken over responsibility for the property, wanted to formalise the tenancy arrangement. It sent the artists a letter outlining the terms of any future tenancy agreement, and attached a 'notice to quit' which would be waived if the artists entered into a binding licence agreement that met conditions set by the ACTPG.

At the same time, the ACTPG engaged a fire consultant to identify deficiencies in the fire safety systems at the property. The ACTPG did not provide the consultant's report to the artists when they served the first notice to quit.

The artists applied for a licence, but the ACTPG did not acknowledge their application. About 18 months later, in December 2008, the ACTPG wrote to the artists and relied on the fire consultant's report to issue a second notice to quit. They were given a short period of time to vacate.

We were approached by the artists after they received the second notice to quit. We decided to investigate and the ACTPG deferred any further action until we completed our enquiries.

We found that the ACTPG had acted properly to protect the government's interests from a liability perspective. However, there was a series of administrative errors that resulted in the artists being treated harshly. The ACTPG did not give the artists an opportunity to consider the recommendations of the fire consultant's report, and did not inform them of the reasons for refusing their application for a licence in 2007. We concluded that a communication delay of 18 months was unreasonable.

The ACTPG and the artists started working together to find an outcome that satisfied both their interests. The ACTPG aimed to protect the government's property interests and the artists sought a community-supported property that allowed them to engage in their work. The ACTPG obtained a second fire report in consultation with the artists. The ACTPG has advised us that all the issues are now resolved, and some minor fire safety works are being arranged together with new licences.

To ensure efficiency in complaint handling, an agency that has resolved a complaint in the past needs to have procedures in place to make sure that the same complaint does not arise again. A recurring error is more likely to happen if the initial error arose as part of an automated system and the system has not been properly updated to correct the information. The case study Correcting mistakes of the past shows how a debt wrongly assigned in 2004 resurfaced in 2009.

Correcting mistakes of the past

Ms J complained that she had applied for housing with Housing ACT and was informed that she had an outstanding debt of more than $4000. Ms J told Housing ACT that the debt did not belong to her and had been the subject of a successful complaint to our office in 2004.

We investigated Ms J's complaint and approached Housing ACT about our previous investigation. We reminded Housing ACT that they had agreed to cancel this debt in 2004 as Ms J was not liable. As a result, Housing ACT apologised to Ms J and advised that she was not liable for the debt.

Housing ACT has conducted a review of its policy and procedures in relation to tenant responsible maintenance. According to Housing ACT, the review will put in place equitable and consistent processes that will be applied prior to raising tenant responsible maintenance charges on tenants' accounts.

Other issues

ACT Corrective Services

The ACT's new prison—the Alexander Maconochie Centre (AMC)—was officially opened on 11 September 2008. Detainees from the BRC and Symonston Temporary Remand Centre moved in from March 2009.

The AMC is now operational and accommodates all ACT detainees. This is a far better situation than previously. ACT detainees were accommodated in the NSW prison system and, when that arrangement ceased, sentenced prisoners and remandees were accommodated in outdated correctional facilities within the ACT.

The BRC was decommissioned on 28 April 2009. It was established in 1976 to provide custodial remand facilities in the ACT for 18 detainees. After extensive renovations over the years it eventually had a maximum capacity of 69 detainees.

However, before it closed, the BRC was accommodating 100 detainees. This was not a satisfactory situation for the detainees, the ACTCS or the community. The shortcomings of the BRC in relation to accommodation, safety and security weighed heavily on ACTCS staff working in the facility, and on the detainees. The increasing numbers of approaches to this office from BRC detainees was indicative of an untenable situation. We commenced an own motion investigation into the response of the ACTCS to an incident between custodial staff and some detainees that occurred in January 2009. We will conclude our investigation in late 2009.

The AMC can accommodate a maximum of 300 detainees. It has been designed as a human rights compliant correctional facility. There is a significant focus in the AMC on rehabilitation and therapeutic programs as well as on detainees obtaining useful work skills that can be applied when they move back into the community. We will monitor the approaches to this office from detainees and keep the ACTCS informed of any emerging trends or systemic issues that may arise.

This office has been working closely with the ACTCS to ensure that it provides timely responses as part of our investigations. We are working together to ensure that complaints from detainees in the AMC are given a high priority by the ACTCS and are considered and resolved promptly.

In our 2007–08 annual report we noted that we had undertaken an investigation into strip-searching procedures at the BRC and Symonston Temporary Remand Centre. At that stage of reporting our investigation was not complete. The case study Law reform needed provides some detail of the investigation. As a result of our investigation, the Legislative Assembly amended the Corrections Management Act to specify more clearly the circumstances in which a strip search of a detainee could be conducted.

Law reform needed

Mr K, a detainee at the BRC, complained that unnecessary strip searches were being undertaken. He was concerned that the real purpose of the strip searches was to train new custodial staff.

We investigated his complaint and while we made no finding in relation to the detainee's allegation, we investigated the ACTCS' interpretation of the strip-searching requirements under the CMA. We concluded that the ACTCS was not complying with the prescriptive strip-searching procedures under the CMA. Under the Act, the ACTCS needed to suspect on reasonable grounds that a detainee was concealing contraband or an item that could pose a safety risk before deciding to conduct a strip search. The ACTCS appeared to be routinely conducting strip searches of detainees after contact visits and when leaving and returning to the facility.

In our view, if a detainee had just had a contact visit or had left the facility—for example, to attend court—this was not a sufficient ground alone to conduct a strip search. The ACTCS agreed with our view that, without more evidence that a detainee had concealed something, the actions of the ACTCS officers were beyond those prescribed by the CMA. The ACTCS sought to have the CMA amended to reflect circumstances where a detainee was outside the direct supervision of custodial staff of the centre, and as a result it may be appropriate to conduct a strip search.

COMPLAINTS—ACT Policing

In the ACT, the AFP undertakes community policing under an agreement between the Commonwealth and ACT Governments. The AFP provides policing services to the ACT in areas such as traffic law, crime prevention, maintaining law and order, investigating criminal activities and responding to critical incidents.

As the AFP is an Australian Government agency, complaints made about AFP officers acting in their ACT Policing role are dealt with by this office under our Commonwealth jurisdiction and through an agreement with the ACT Government.

Before 30 December 2006, complaints about the AFP were handled by the AFP and oversighted by the Ombudsman under the Complaints (Australian Federal Police) Act 1981 (Complaints Act). At the end of 2007–08, 31 complaints made under the Complaints Act were outstanding and all were finalised in 2008–09.

Complaints about the AFP made since 30 December 2006 are dealt with by the AFP under the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (AFP Act) and may also be investigated by the Ombudsman under the Ombudsman Act 1976 (Cth). The Ombudsman does not oversight the handling of every complaint, but is notified by the AFP of complaints it receives that are categorised as serious conduct issues. The Ombudsman also periodically reviews the AFP's complaint handling.

Review of complaint handling

The Ombudsman has a responsibility under s 40XA of the AFP Act to review the administration of the AFP's handling of complaints, through inspection of AFP records. This includes records of the handling of complaints about ACT Policing. Generally two reviews are conducted each year and the Ombudsman reports to the Commonwealth Parliament annually, commenting on the adequacy and comprehensiveness of the AFP's dealing with conduct and practices issues, as well as its handling of any inquiries ordered by the federal minister.

The most recent report to the Commonwealth Parliament, covering review activities conducted during 2007–08, was tabled in November 2008. The report noted that the AFP had made extensive preparations for its new complaint-handling system and had a genuine commitment to making it work. Nevertheless, room for improvement was identified in relation to the:

- technology used by the AFP for recording, managing and tracking complaints

- timeliness of the AFP's handling of minor complaints, which was consistently well below the benchmarks that the AFP had set itself

- need for the AFP to make use of complaint information to improve practices and procedures on an organisational basis

- AFP attitude to, and dealings with, complainants.

During the reporting period, the office conducted inspections to review the AFP's administration of complaint handling under Part V of the AFP Act in September-October 2008 and March 2009. The review arising from the first inspection was finalised in April 2009 and the review arising from the second inspection should be finalised in the first quarter of 2009–10.

This year's reviews noted a pleasing improvement in most areas of AFP complaint handling from the previous years. In particular, the AFP provided resources to upgrade its information technology system for recording and managing complaints, which is expected to result in better functionality and reporting capabilities. Timeliness in the handling of minor complaints improved. The AFP also improved its practices and procedures for dealing with complainants. Further details on these reviews will be contained in the 2009 report to Parliament.

Complaints received

In 2008–09 we received 176 complaints about AFP members acting in their ACT Policing role. The most common issues raised by complainants included:

- minor misconduct, including inappropriate behaviour and harassment

- failure to act and inadequate investigation

- inadequate advice and service

- traffic matters.

Complaints finalised

During 2008–09, we finalised our oversight of 31 complaints under the Complaints Act, and 174 approaches and complaints under the Ombudsman Act.

We referred 111 (64%) of the 174 finalised Ombudsman Act approaches and complaints back to the AFP as the complainants had not approached the agency. We advised a further six complainants to consider pursuing the matter at court and one complainant was referred to another oversight body.

We declined to investigate another 47 (27%) of the complaints, for reasons such as:

- the matter was out of jurisdiction

- the complaint was withdrawn or lapsed

- we requested further information which was not received

- the matter had been considered by a court

- investigation was not warranted in all the circumstances.

We investigated and closed nine complaints. At the end of the financial year 12 complaints were still open, including four under investigation at that stage.

In some cases investigation of a complaint can lead to an improvement in procedures and documentation. The case study Wrong interpretation shows the outcome from one complaint we investigated under the Ombudsman Act.

Wrong interpretation

Ms L complained that when she went to the City Watchhouse to see her son who had been detained earlier that day, she was denied access to him.

Our investigation established that when her son was admitted, he was asked the question 'If anyone should call here whilst you are in custody saying that they are a friend of yours, a member of your family or a legal practitioner acting on your behalf, do you have any objections to them being told you are here?' The answer given was 'Yes, that's fine'. The Constable recorded the answer to the question as 'Yes'. This then marked the record with an indication that he had requested privacy. When Ms L asked to visit her son, the duty officer noted that her son had asked for privacy and refused her request.

When we investigated the complaint, the AFP advised that the question relating to privacy had been reworded. The question now asked is 'If anyone calls the Watchhouse, can we tell them you are here?' This question appears to be less open to misinterpretation.

A common theme in complaints in many agencies is that some problems can be prevented by providing a better explanation at the outset. The case study No prosecution demonstrates how this applied in one complaint about the AFP that we investigated.

No prosecution

Mr M complained that the AFP failed to adequately investigate the theft of property from his motor vehicle, and later that the AFP's Professional Standards failed to provide adequate reasons for their decision that his complaint was not established.

Following our investigation, the AFP wrote to Mr M with a more detailed explanation of the reasons ACT Policing decided that there was insufficient evidence to commence any prosecution in relation to the theft from his motor vehicle.

Critical incidents

The AFP notifies the Ombudsman of all critical incidents involving the actions of AFP officers. An incident may be treated as critical where it involves AFP appointees and results in the death or serious injury of a person and involves a motor vehicle, a person in custody, the discharge of a firearm or the application of force. Incidents that result in major damage to property and that involve AFP appointees may also be considered critical. Usually we do not become actively involved in the investigation of critical incidents unless the AFP requests our involvement.

During 2008–09 one critical incident was reported. In June 2009 an AFP officer attempted to stop a vehicle suspected of exceeding the speed limit. The subject vehicle attempted to flee and drove through a red light, colliding with several vehicles. There were no serious injuries. The police treated the matter as an accident in the course of a pursuit. The matter is ongoing.

Exercise of police responsibilities under the Intoxicated People Act

In October 2008 the Ombudsman completed an own motion investigation of the AFP's use of powers under the ACT Intoxicated People (Care and Protection) Act 1994 (IPCP Act). The report is available on the Commonwealth Ombudsman website at www.ombudsman.gov.au.

This was the third such investigation, following Ombudsman reports in 1998 and 2001. The establishment of an ACT sobering up shelter, operated by Centacare, was an important change since those earlier reports. The report made 14 recommendations. In summary, the report recommended:

- AFP training material on the IPCP Act should be revised to:

- emphasise the care and protection aim of the Act and distinguish powers under those provisions clearly from street offences

- provide more guidance to police on the circumstances in which use of the IPCP Act provisions is appropriate compared with other options, including breach of the peace and charging with a substantive offence.

- AFP training in de-escalation of conflict should be increased, emphasising dealing with people affected by alcohol or other drugs.

- The AFP should review and update the guidelines relating to breach of the peace to specify how intoxicated people should be dealt with, given there may be concerns about their capacity to understand fully the consequences of giving an undertaking as a condition of release.

- All ACT Policing members should receive initial and ongoing training on the risks arising in the transport and custody of intoxicated people.

- ACT Health (as the agency with policy responsibility for the IPCP Act) should ensure that a memorandum of understanding is in place between Centacare and the AFP.

- The AFP and ACT Health should work together with Centacare to ensure a high degree of consistency in eligibility criteria in Shelter and AFP guidelines.

- The AFP should ensure that appropriate ACT Policing training enhances police awareness of, and confidence in, the Sobering Up Shelter.

- The AFP should amend its Sobering Up Facility guidelines so that Indigenous people are not precluded from consideration for diversion to the Sobering Up Shelter, and similarly for other people defined as 'at risk' in police custody.

- The AFP should amend the Watchhouse Manual to ensure that:

- the officer-in-charge considers before admitting an intoxicated person whether that person would be more appropriately cared for at the Sobering Up Shelter

- people detained for intoxication are asked on admission whether they wish to nominate a responsible person into whose care they may be released at some future point if the officer-in-charge considers it appropriate.

- The AFP should amend the Watchhouse Manual to ensure that those people who are detained under the IPCP Act are allowed to contact their lawyer.

- The AFP should ensure that officers accurately and consistently record lodgement and release times. This may require considering redesign of the AFP PROMIS database to include prompts to minimise mistakes in use of the 24-hour clock.

- The AFP should amend its guidelines to ensure that the officer-in-charge of the Watchhouse reviews an intoxicated person's detention after four hours to determine whether the person may be released into the care of a responsible person or otherwise allowed to leave, and that this review is documented in the Cell Management System.

- The AFP should ensure that where a person detained for intoxication asks to stay at the Watchhouse beyond the eight-hour limit, the person's consent is always recorded in the Cell Management System.

- The AFP should amend the Watchhouse Manual to remove any reference by police of 'rolling detentions' of periods of eight hours.

The AFP responded to the report by noting that it was willing to consider the majority of the recommendations, but that for some it believed that additional action was not necessary or appropriate.

We followed up on the implementation of the recommendations. We received a response after the reporting period indicating that while some additional progress had been made, a number of the recommendations which the AFP supported were still not implemented fully (in particular, the recommendations that related to the relationship with Centacare).

Review of Watchhouse operations

In our 2007–08 annual report we noted that the results of a joint AFP/Ombudsman review of the ACT Policing's Watchhouse operations were released in June 2007 and that a joint Steering Committee was established to follow up the recommendations.

The Ombudsman wrote to the AFP Commissioner in August 2008 following the finalisation of the Steering Committee's report on the implementation of the review's recommendations. The Ombudsman referred to three areas that required attention—governance, detainee health and wellbeing, and use of force. The Ombudsman noted he would continue to closely monitor complaints about Watchhouse operations. The Chief Police Officer of the ACT undertook to conduct an ACT Policing review of implementation in approximately six months.

In March 2009 the AFP provided the Ombudsman with the Report to ACT Chief Police Officer on Implementation of Recommendations of the June 2007 Review of ACT Policing's [Regional Watchhouse] Operations. The report demonstrated a thorough acquittal of the recommendations of the Watchhouse review. The issues raised by the Ombudsman have either been addressed or are in the final stages of completion. Training in appropriate use of force in the Watchhouse has been implemented and amendments to Commissioner's Order 3 are in train. One issue outstanding is the removal of hanging points in the Watchhouse, for which ACT Government funding is being sought.

The Ombudsman will continue to monitor Watchhouse practices and conduct in the context of addressing complaints.

INSPECTIONS—ACT Policing

ACT Child Sex Offenders Register

The ACT Child Sex Offenders Register was established as a requirement of the Crimes (Child Sex Offenders) Act 2005 (ACT). The Register must contain up-to-date information relating to the identity and whereabouts of people residing in the ACT who have been convicted of sexual offences against children. One of the ACT Ombudsman's functions is to inspect the register to ensure that it is accurately maintained by ACT Policing.

This office has conducted three inspections of the register since the register commenced operation on 29 December 2005. The Ombudsman provided the report of the second inspection, carried out in June 2008, to the Minister for Police and Emergency Services and the ACT Chief Police Officer during the reporting period. The Ombudsman found that ACT Policing is generally compliant with the relevant provisions of the Act and that the register is being maintained appropriately. We conducted the third inspection of the register in June 2009 and are finalising the report from this inspection. It is our intention to conduct inspections on an as-required basis, but at least every 12 months.

ACT controlled operations

On 19 August 2008 the Crimes (Controlled Operations) Act 2008 (ACT) came into effect. This Act allows ACT Policing to conduct controlled operations in the ACT and gives oversight to the Ombudsman. A controlled operation is a covert operation carried out by law enforcement officers under the Crimes (Controlled Operations) Act for the purpose of obtaining evidence that may lead to the prosecution of a person for a serious offence. The operation may result in law enforcement officers engaging in conduct that would constitute an offence unless authorised under this Act.

We have not conducted any inspections of ACT Policing in relation to controlled operations as the provisions under the new legislation have not yet been used. Currently we are assisting ACT Policing to develop processes for using the new legislation, based on our experience in monitoring controlled operations conducted by the AFP and the Australian Crime Commission under Commonwealth legislation.